Above: Mato (drums) and Jon (seated) during drum tracking. Recognize the space? If so, you are one of the 12 people who saw this cinematic debacle, filmed largely in this very building.

Above: Mato (drums) and Jon (seated) during drum tracking. Recognize the space? If so, you are one of the 12 people who saw this cinematic debacle, filmed largely in this very building.

Several years ago, before I had Gold Coast Recorders, I had a modest recording-studio setup in the former American Fabrics factory on the east side. It was a small operation with a large control room and two small ‘booths’ with observation windows linking all the spaces. Nothing fancy, but I did manage to make a number of successful productions there. NEways… due to the very small size of the tracking rooms I sometimes resorted to tracking after-hours and on weekends in other parts of the floor. A few tracks from one of my final sessions there were recently released.

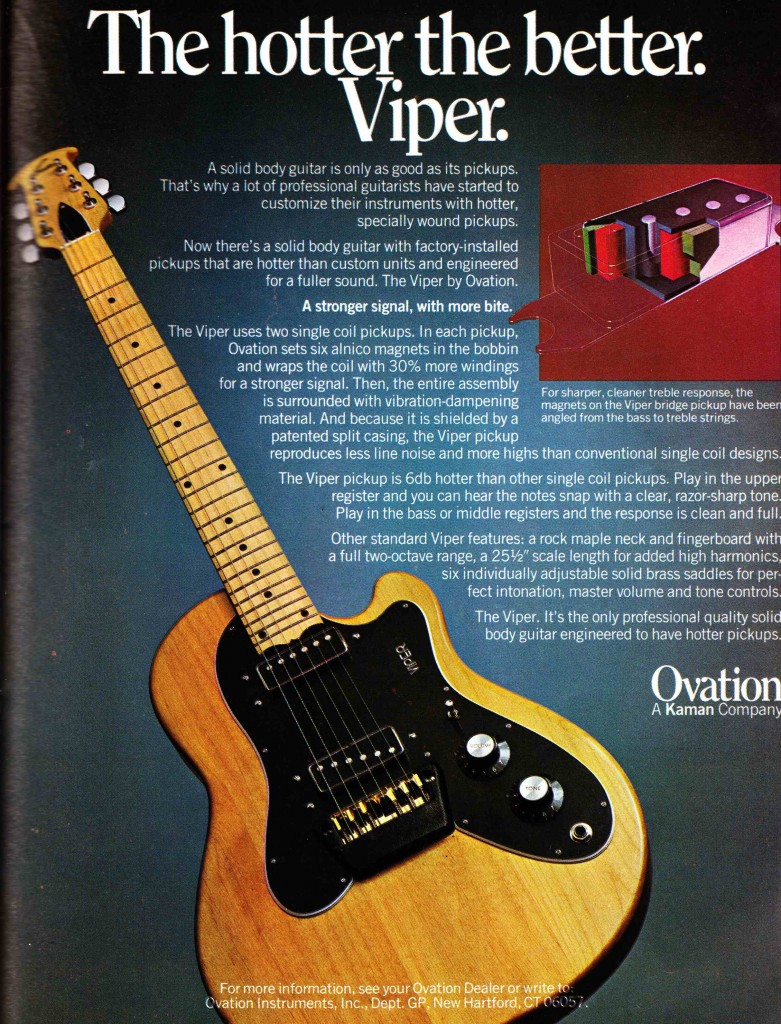

Have a listen to “Brass Bonanza,” the lead-off track from Five Minute Major (In D Minor), the latest album by The Zambonis. The record was released in February 2012 to great response from The New Yorker, The Examiner, and NPR.

Have a listen to “Brass Bonanza,” the lead-off track from Five Minute Major (In D Minor), the latest album by The Zambonis. The record was released in February 2012 to great response from The New Yorker, The Examiner, and NPR.

LISTEN: Brass Bonanza

Horn tracking space for “Brass Bonanza.”

Horn tracking space for “Brass Bonanza.”

I love Pro Tools. I’m not afraid to say it. I love the convenience, the low cost, the rapid editing ability, the fact that it leaves essentially no limits to music production other than the imagination and the skill of the artists/engineer. And while I tend to use plug-ins (audio-processing sub-programs that run within the pro tools software body) for more corrective rather than creative purposes, preferring to ‘get-the-right-sound-on-the-way-in,’ I don’t have many issues with how they sound either. The one thing, the one little thing that I can’t quite fall-in-with, though, is digital reverb.

Back in the ole’ days when I used a Yamaha Rev7 and ADATs I really did not mind the sound of digital reverb; the recording media was lower-resolution, the Rev7 was 12-bit and had much less high-frequency content to begin with, and I was certainly less critical of a listener. In my current set-up of Pro Tools HD3 with Lynx convertors and a properly tuned control room, though, I just can’t seem to fool myself into thinking that the digital reverb plug-ins effectively create the sound of an actual space. Not that this is the only possible function of reverb; reverb is also useful for smoothing out pitch issues and simply creating multiple planes of depth within a sonic field. But when I’m recording a rock band, trying to capture the energy and volume of a performance, I feel like it does the band the most justice to ‘put it in a space.’ And what better space than real space? In the case of ‘Brass Bonanza,’ there was no artificial reverberation used. The drums were tracked in the space that you see them in: approximately 30% of the way along a 100-foot hallway. The horns were tracked in the tiled restroom that you see, with the single ribbon mic depicted in the photo. How much additional value/merit does this give to the recording versus running a reverb plug in? That’s up to you to decide. The band wanted a very reverberant sound and the only way that I can be satisfied with heavy reverb is if it has some if the complexity, texture, and non-linearity that a real space offers.

So what do you do if you don’t have a 100-foot hallway or an 1100-sq ft live room to track drums in? I’ll begin with some advice given to me several years ago by the great producer Martin Bisi. I was subletting studio space from Martin at the time and in one of our many wonderful conversations Martin offered me this bit of wisdom which I paraphrase for you here. Life is complex; reality is complex. What we experience in the world is complex. The more sonic complexity you introduce into a recording, the closer you come to recreating actual lived experience. I hesitate to say “you make it life-like,” since this is ultimately not possible, but you get closer to that impossible goal.

So if this is true, what does it mean for process? Well, first of all, notice that there is no mention here of musical complexity. We’re talking about adding sonic interest to a musical performance. This ultimately holds the promise of allowing us to simplify and streamline the musical lines/performances while still creating and maintaining a huge amount of interest for the listener. With enough detail, care, and complexity achieved in the audio rendering of a musical performance, even the most utterly simple melody, phrase, line, or note can create incredible meaning. This is the most basic, and the most profound, goal of creative audio engineering.

Second, but no less important, is this idea that perhaps it is the complexity of the sonic-event, and not necessarily any verisimilitude to any actual acoustic even/space, that really matters most. So while I may have coveted the sound of that long hallway and that super-reflective restroom, perhaps what I really gain from those sonic generators is the infinite amount of complexity that they bring to the sound, and not necessarily the fact that I think the qualities of actual physical space are accurately described in the mix. Here’s something you can try at home. Create your mix using whatever digital reverb tools you have. Print the output of the reverb as an audio stem. Solo that stem. Find the space in your house/apartment/studio that has the most interesting sonic quality and a pleasing frequency-response character. Put your monitor speakers and a stereo pair of mics in that space and re-amp the reverb stem only. Record that to its own stereo track. You have now added an infinite (within the limitations of the A/D convertors) amount of complexity to a digital reverb that is, necessarily, somewhat limited in detail. See if this new, 2nd-generation reverb adds interest and complexity to the mix. You will probably need to EQ it a bit, but you can do this fairly easily by using the first-generation digital print as a guide. Consider using this 2nd gen reverb as perhaps a ‘spotlight’ reverb for the ld vox, chorus snare drum, or percussion stem. When we re-orient our awareness to the problem/promise of complexity in sound-recordings rather than fidelity, great things can and will happen.

You can learn more about The Zambonis and stream their new record at TheZambonis.com. “Brass Bonanza” and “Fight On The Ice” are my two productions on the record; the rest of the album was produced and engineered by the great Peter Katis and Greg Giorgio at the world-renowned Tarquin Studios, also located in scenic Bridgeport Connecticut.

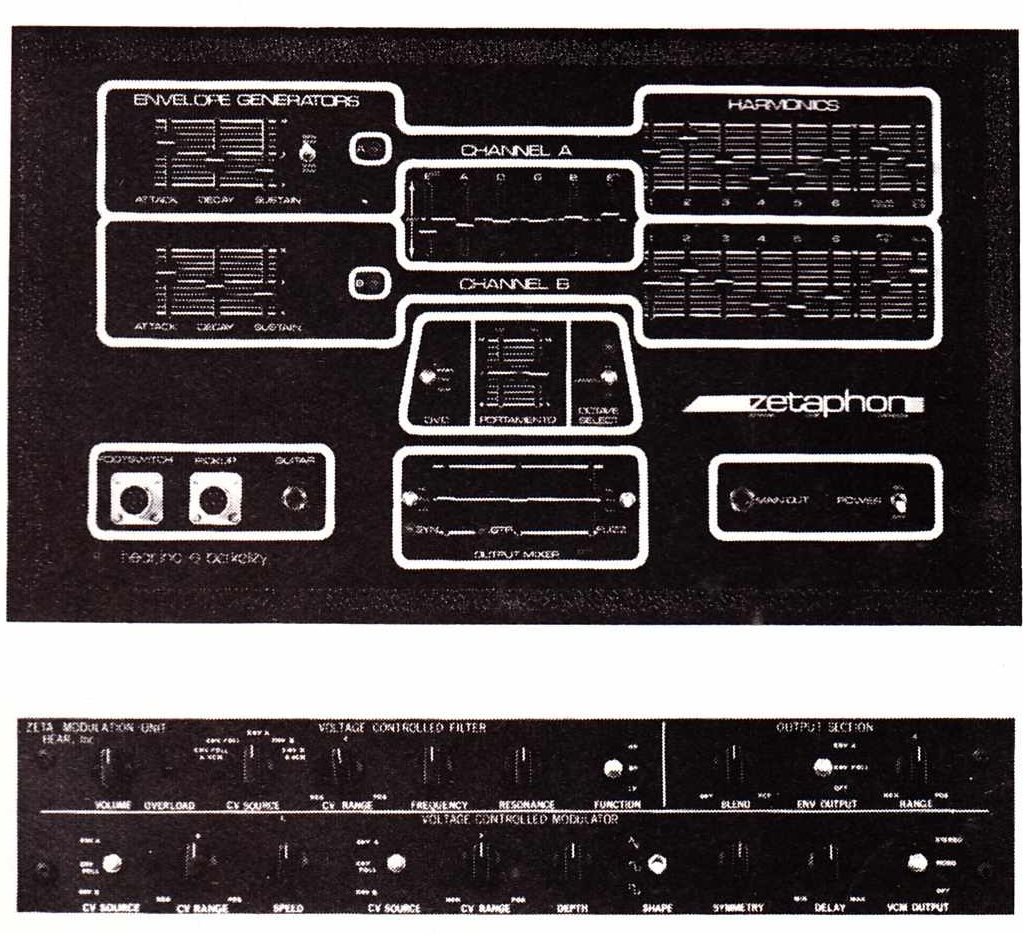

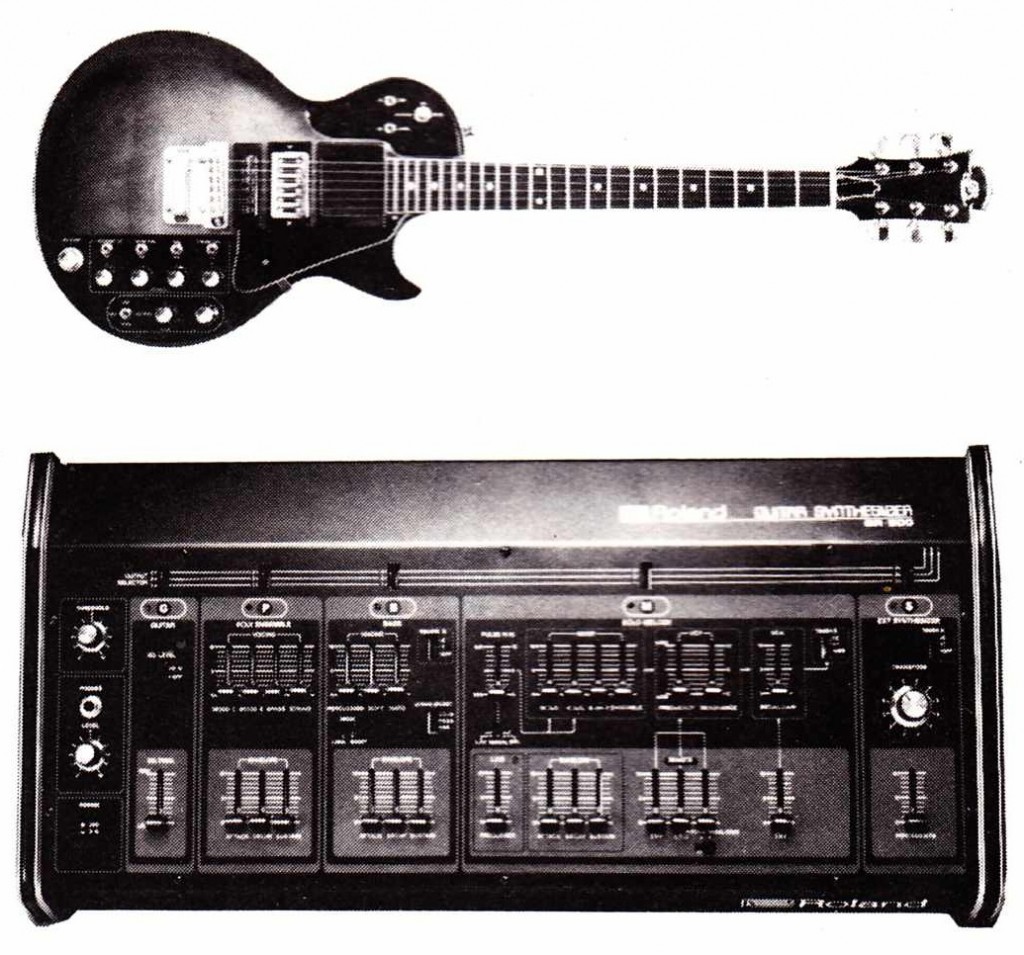

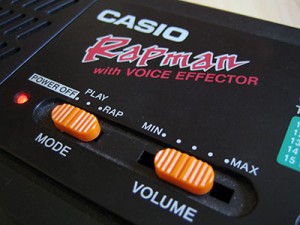

The Rapman (see here for a detailed analysis of its feature-set and cultural positioning) is an early example of the trend to market synthesizers towards performers of specific genres of music. Other notable examples (and there are many more…) include the E-Mu Planet Phatt and Orbit (hip hop and dance, respectively).

The Rapman (see here for a detailed analysis of its feature-set and cultural positioning) is an early example of the trend to market synthesizers towards performers of specific genres of music. Other notable examples (and there are many more…) include the E-Mu Planet Phatt and Orbit (hip hop and dance, respectively).