Download the twenty-page 1956 Gibson Electric Guitars and Amplifiers Catalog:

Download the twenty-page 1956 Gibson Electric Guitars and Amplifiers Catalog:

DOWNLOAD: Gibson_Elec_1956_cat

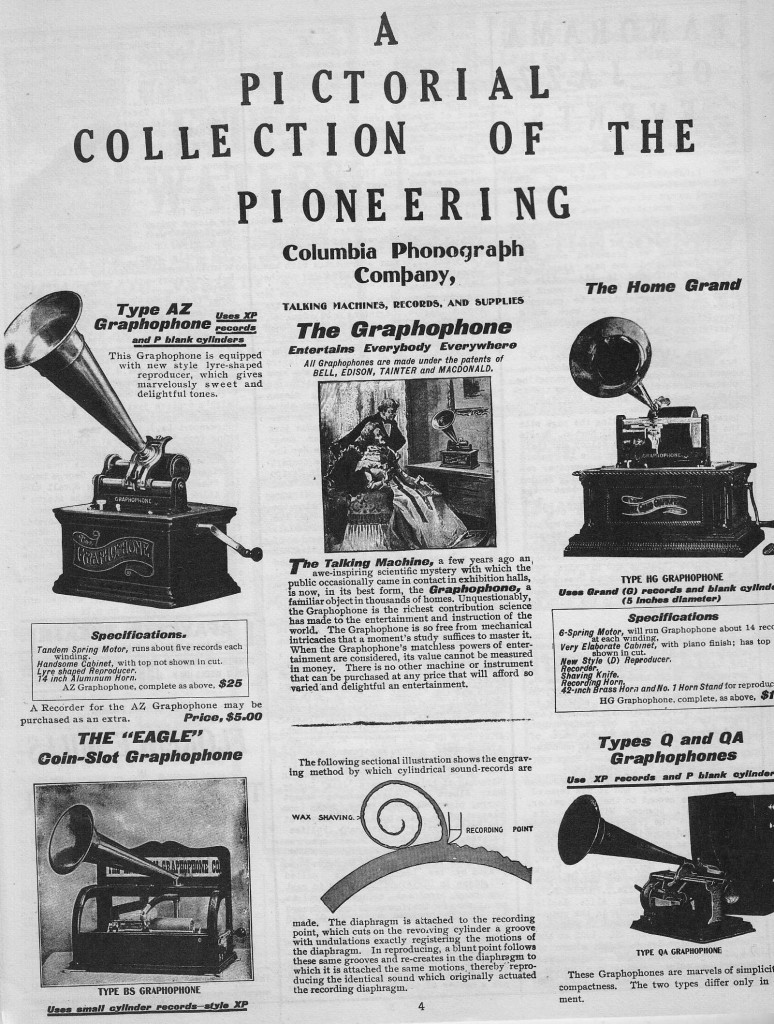

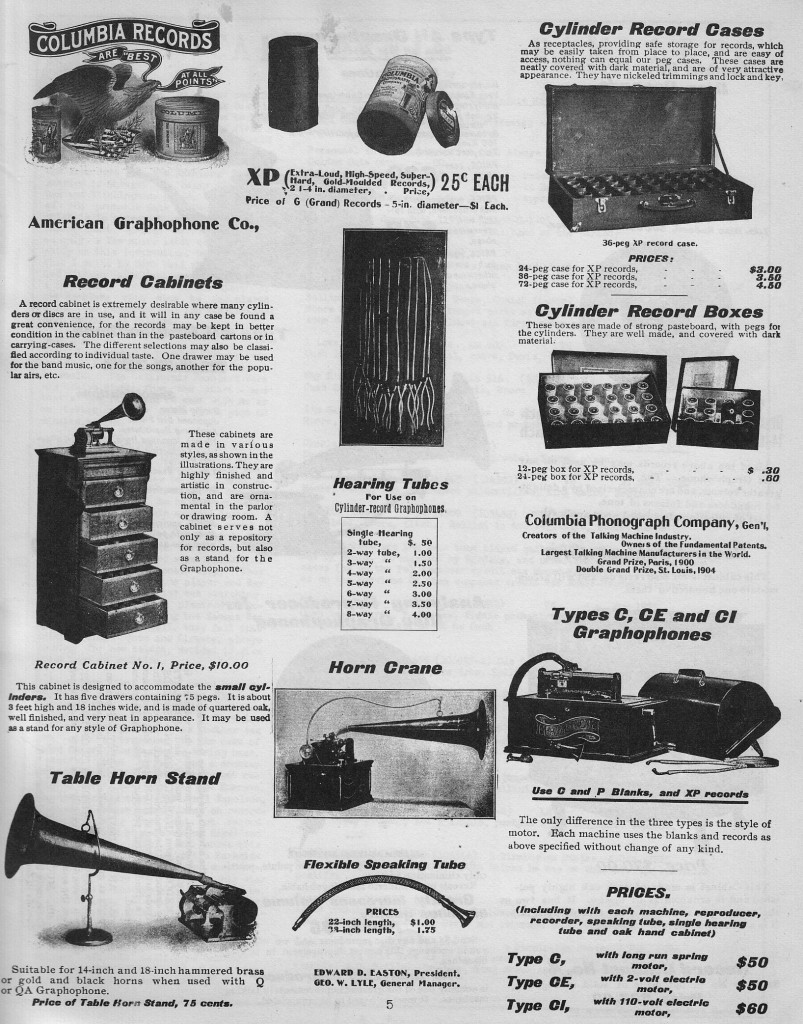

Products covered, with text, specs, and photos, include: Gibson Super 400 CESN, L-5 CESN, ES-5 Switchmaster, Byrdland, ES-175, ES-175 DN, ES-350T, ES-125, ES-295, and ES-240 hollow-body electric guitars, Gibson GA-90, GA-77, GA-55 V, GA-70, GA-40 ‘Les Paul,’ GA-30, GA-20, GA-6, GA-9, and Gibsonette amplifiers; Gibson Les Paul Custom, Les Paul, Les Paul special, Les Paul Junior, and ES-225 electric guitars; Gibson J-160 E acoustic/electric, EM-150 electric mandolin, Gibson Electric Bass; Ultratone, Century, BR-6, Console Grande, Consolette, Electraharp, and Multiharp steel guitars, plus more.

The 1956 GA-90 ‘High-Fidelity Amplifier,’ with six 8″ speakers and promised 20-20K hz frequency response (really?).

The 1956 GA-90 ‘High-Fidelity Amplifier,’ with six 8″ speakers and promised 20-20K hz frequency response (really?).

This very rare catalog is something special for fans of the electric guitar. We see a number of trends developing – the solidbody electric guitar, ‘true vibrato’ circuits in amplifiers, high-wattage amps… and a few notably absent: humbucking pickups and amplifier reverb. These were right around the bend though… Download and enjoy.

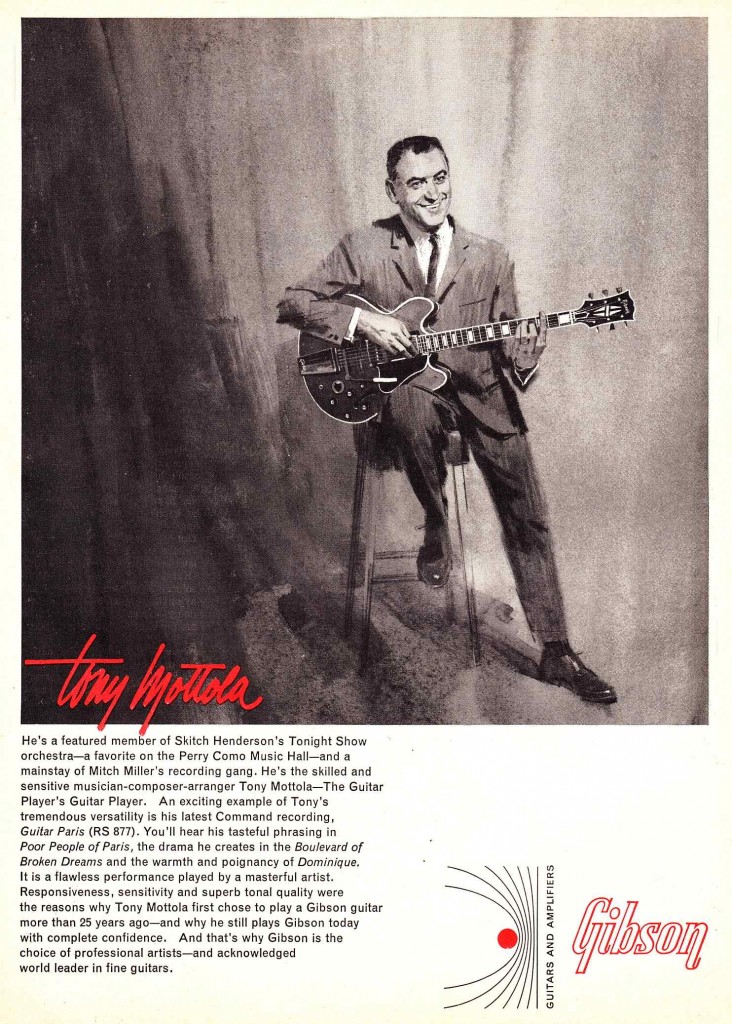

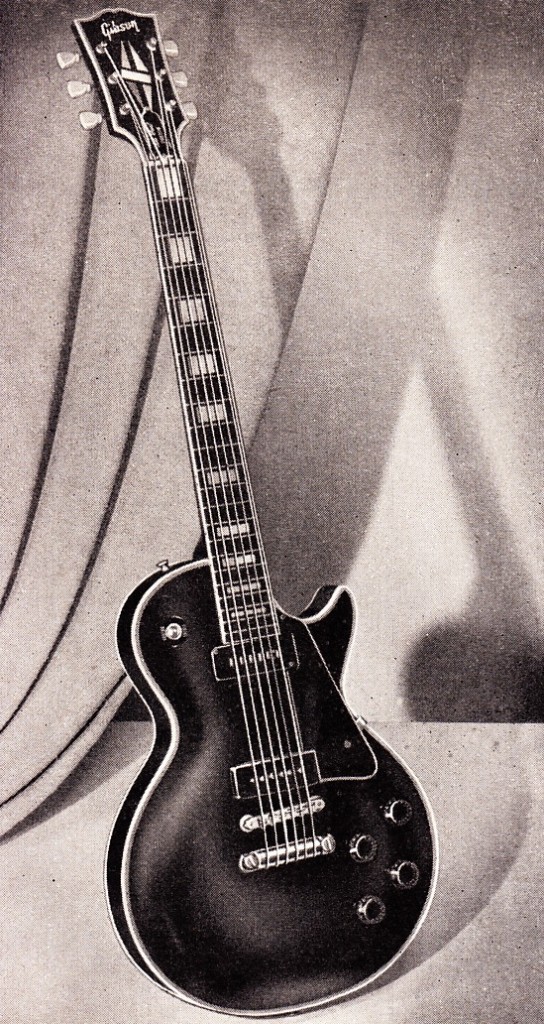

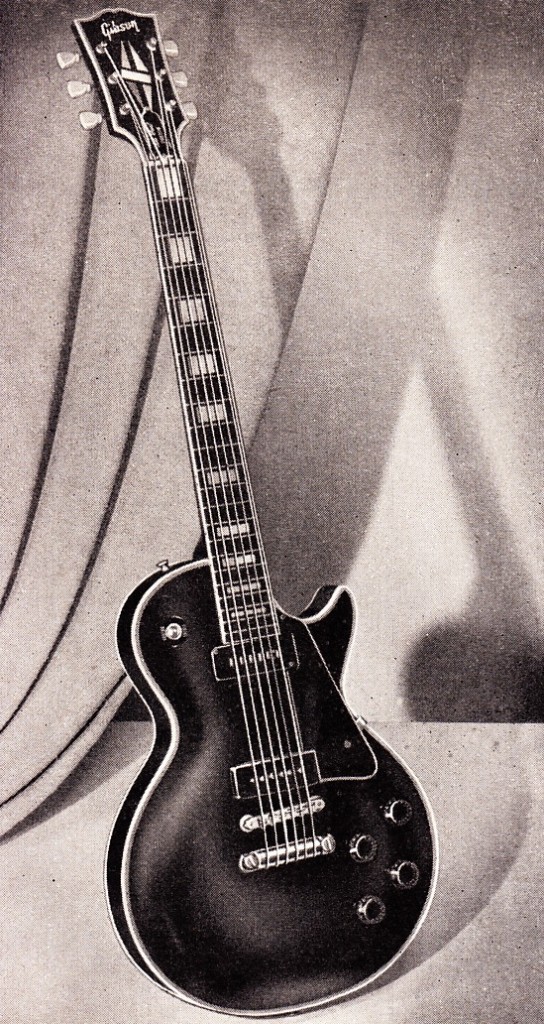

Original catalog image of the 1956 Gibson Les Paul Custom

Original catalog image of the 1956 Gibson Les Paul Custom

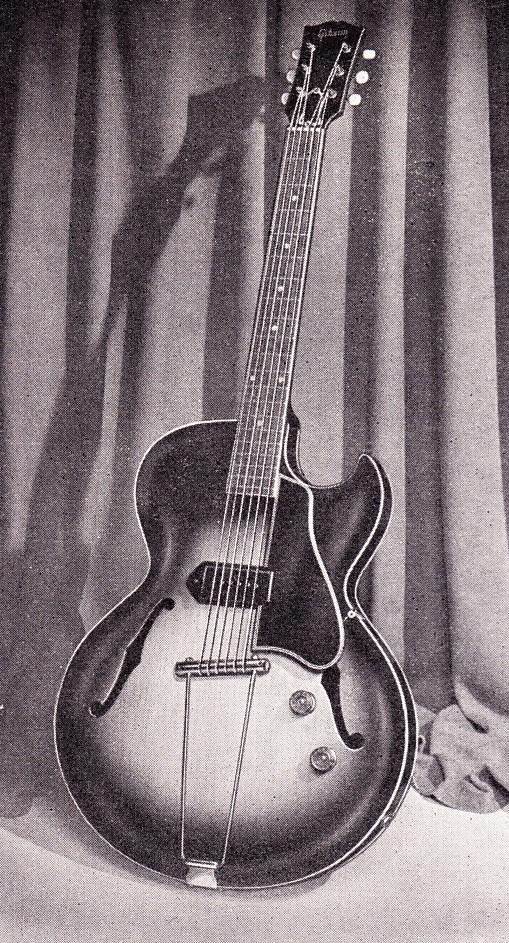

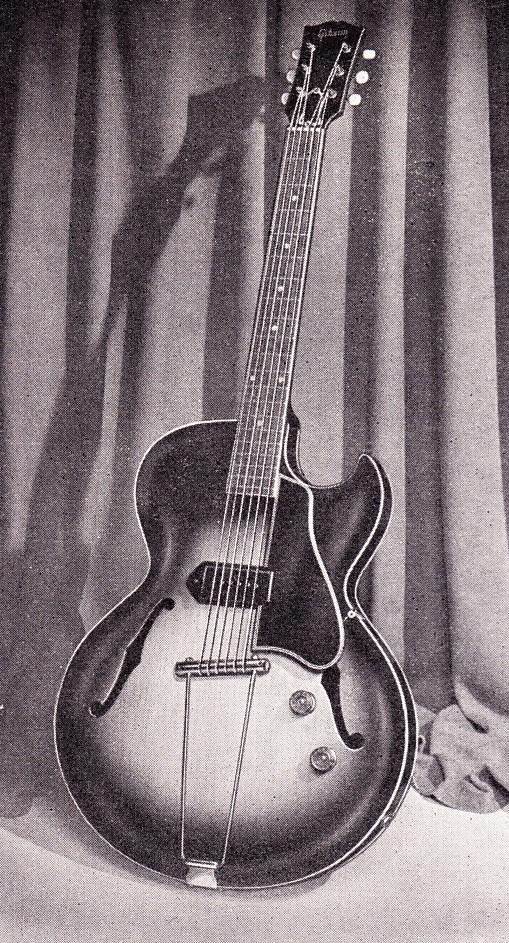

Gibson’s 1956 ES-225T, the first of their many semi-hollow body guitars, the most iconic of which is the ES-335. I borrowed a friend’s ES-225T for a few weeks in high school and I still have very fond memories of it… great guitars, very expensive today.

Gibson’s 1956 ES-225T, the first of their many semi-hollow body guitars, the most iconic of which is the ES-335. I borrowed a friend’s ES-225T for a few weeks in high school and I still have very fond memories of it… great guitars, very expensive today.

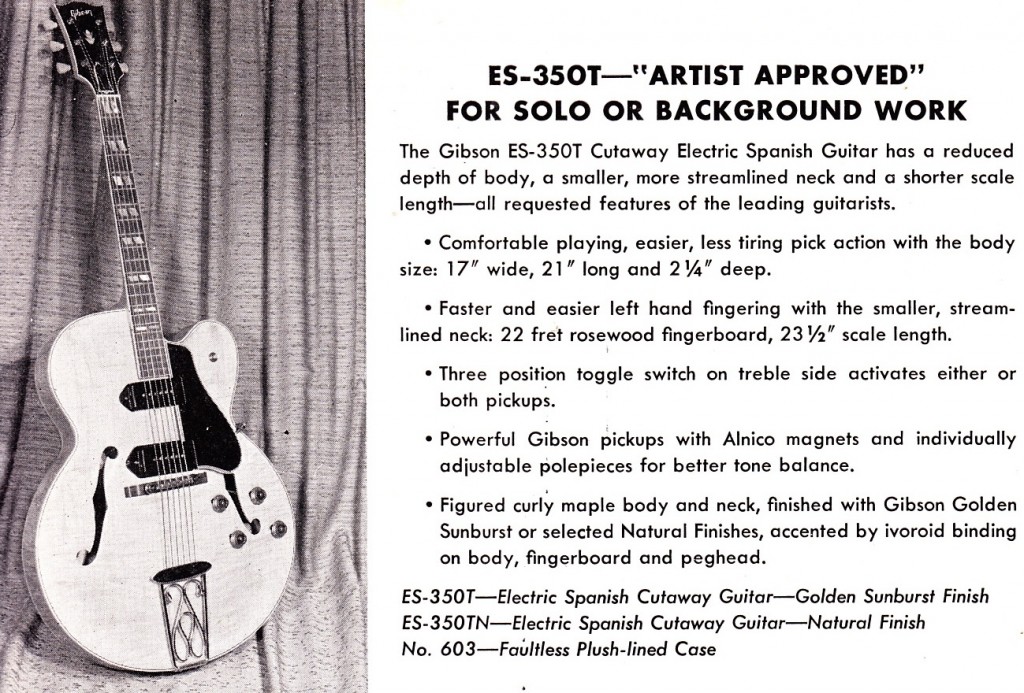

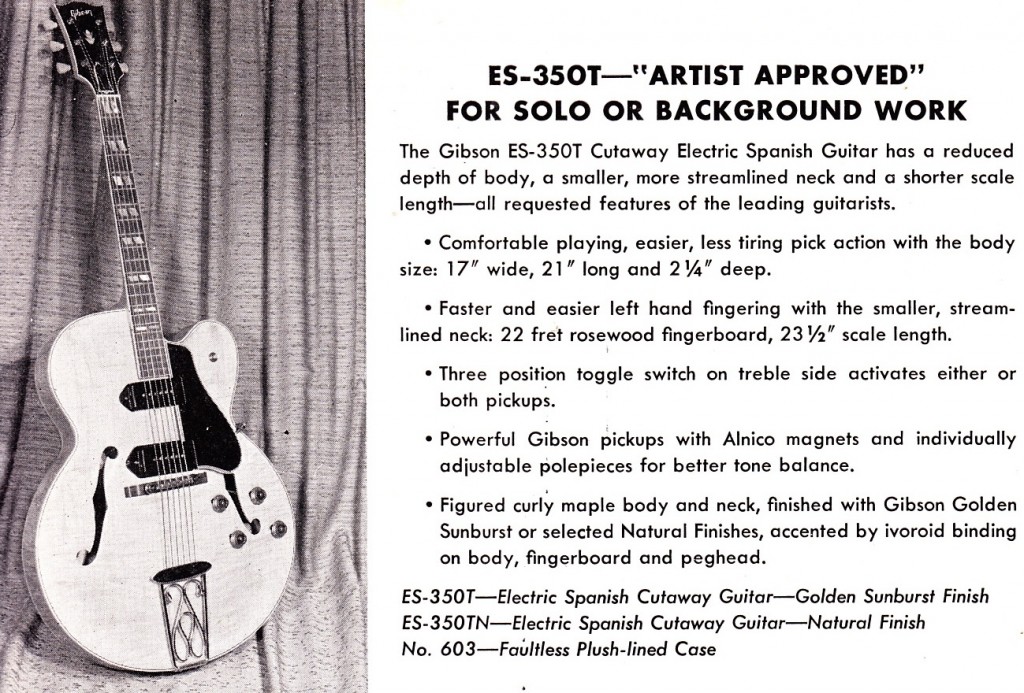

The 1956 Gibson 350T. A slightly less-fancy Byrdland, also with a medium-scale neck.

The 1956 Gibson 350T. A slightly less-fancy Byrdland, also with a medium-scale neck.

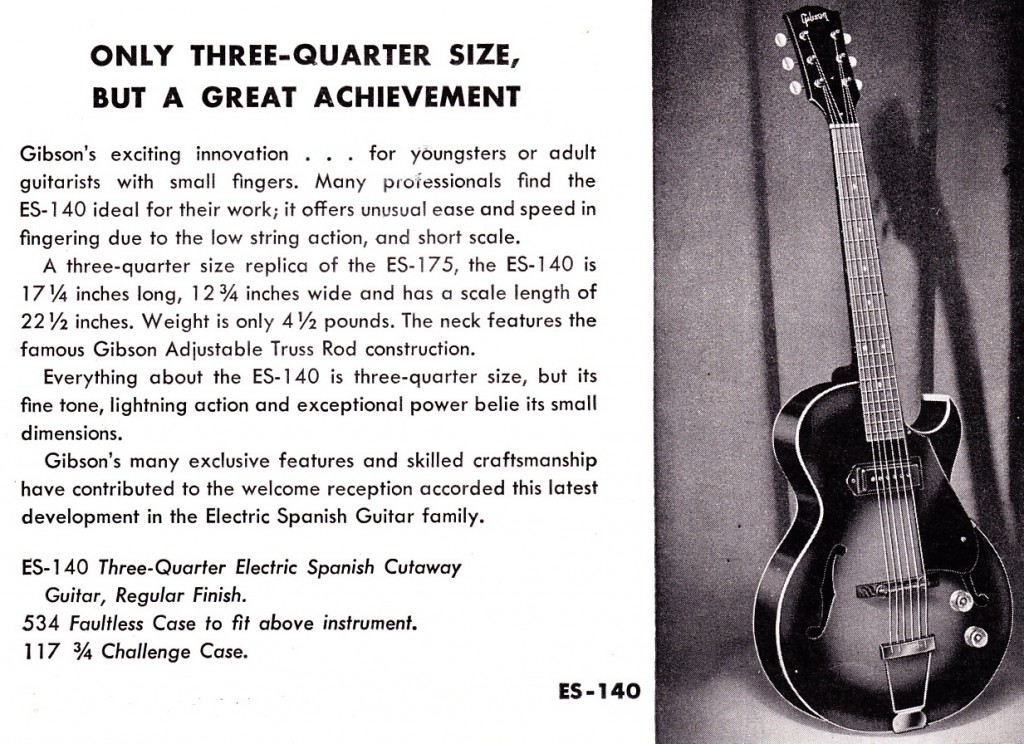

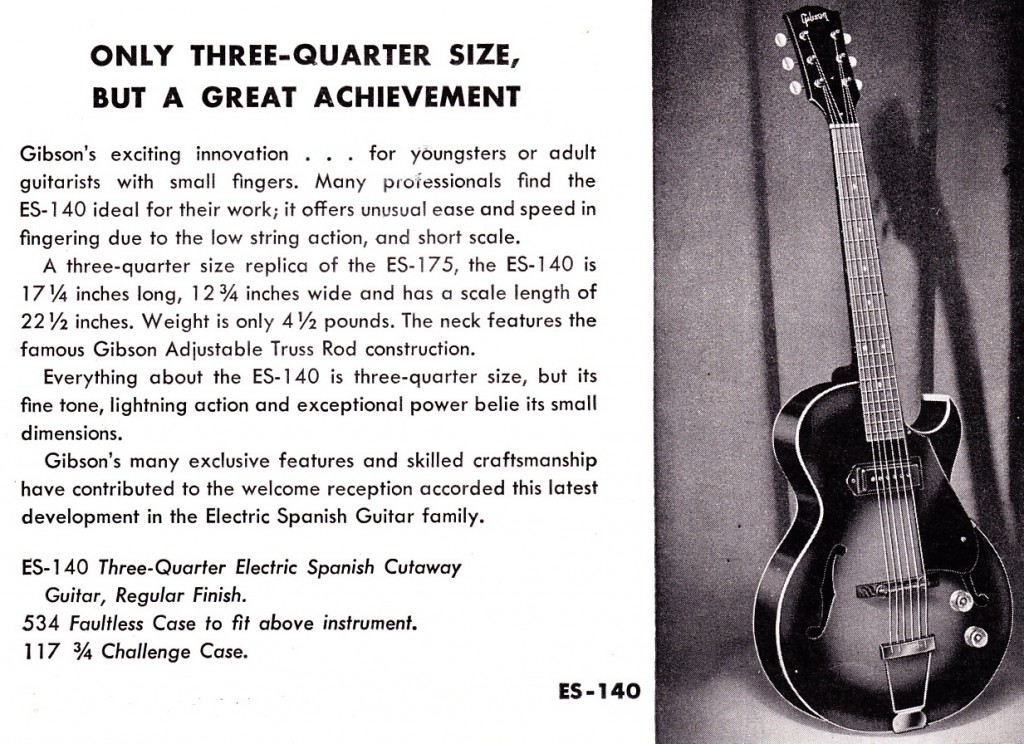

The 1956 Gibson ES-140, their short-scale offering of the era. An artist whom I regularly work with at Gold Coast Recorders often brings one of these to sessions, and it is a seriously fun sitting-on-the-couch guitar with a seriously noisy single-coil pickup.

The 1956 Gibson GA-6, one of their most classic amps. Very similar to a Tweed Fender Deluxe. Fantastic amplifier.

The 1956 Gibson GA-6, one of their most classic amps. Very similar to a Tweed Fender Deluxe. Fantastic amplifier.

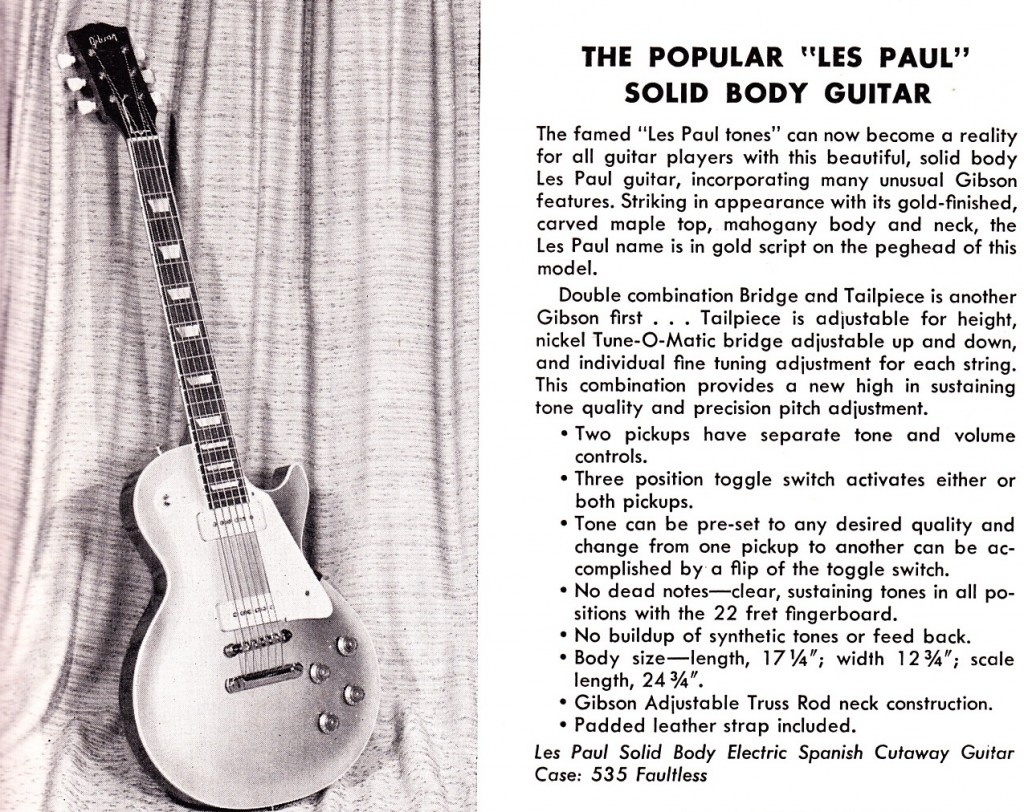

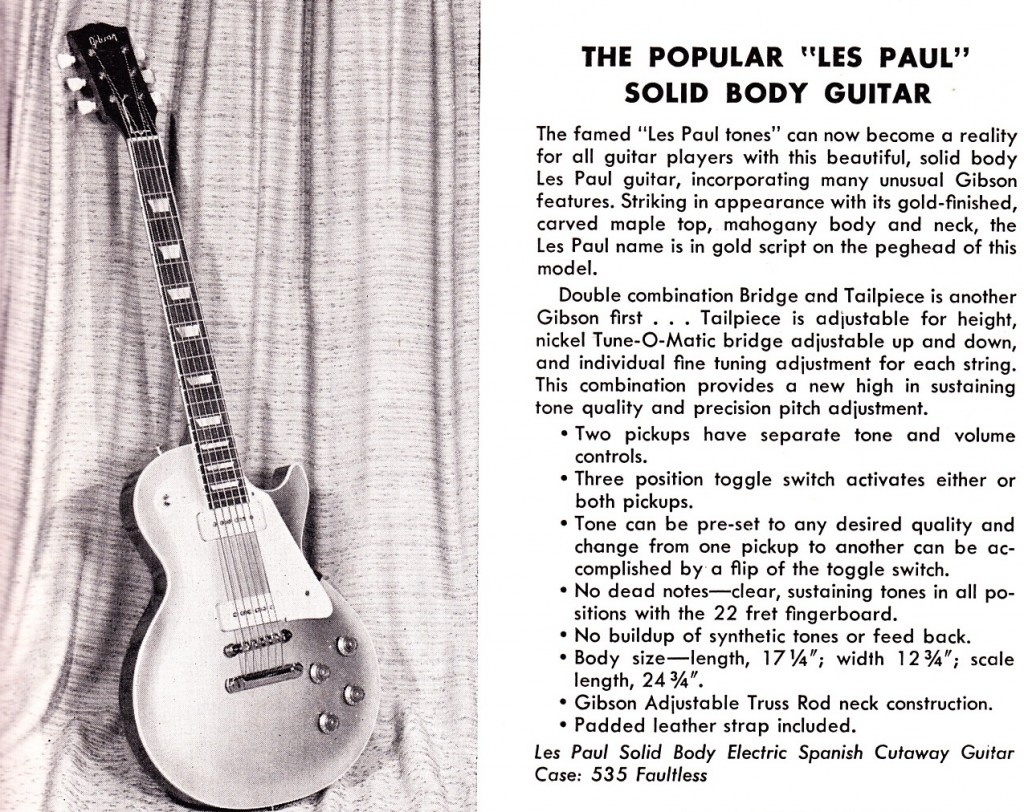

The 1956 Gibson Les Paul. We have a clone of one of these (based on a 1972 Gibson Les Paul Deluxe) at Gold Coast Recorders and it sounds great. 1956 was an important year in the development of the Les Paul as it marked the appearance of the tune-a-matic bridge: it was now possible to intonate your guitar quickly and accurately, AND also customize the string feel and sustain characteristic by setting the stud to get the break angle that you want.

The 1956 Gibson Les Paul. We have a clone of one of these (based on a 1972 Gibson Les Paul Deluxe) at Gold Coast Recorders and it sounds great. 1956 was an important year in the development of the Les Paul as it marked the appearance of the tune-a-matic bridge: it was now possible to intonate your guitar quickly and accurately, AND also customize the string feel and sustain characteristic by setting the stud to get the break angle that you want.

Feeling a bit of an 80s thing right now. Jesus Christ you baby boomers. You grew up in the 1950s, all industry and productivity and abundance (and unchecked racism, sexism, and cold war terror), and THEN you got the 1960s, unheralded change, motion, sexual freedom, drugs, Godard, Psych, Soul, and space travel (and the draft). When the 50s repeated themselves in the 80s, things seemed fairly optimistic. And then we got the 90s. Now as much as I love Pavement and email…

Feeling a bit of an 80s thing right now. Jesus Christ you baby boomers. You grew up in the 1950s, all industry and productivity and abundance (and unchecked racism, sexism, and cold war terror), and THEN you got the 1960s, unheralded change, motion, sexual freedom, drugs, Godard, Psych, Soul, and space travel (and the draft). When the 50s repeated themselves in the 80s, things seemed fairly optimistic. And then we got the 90s. Now as much as I love Pavement and email…