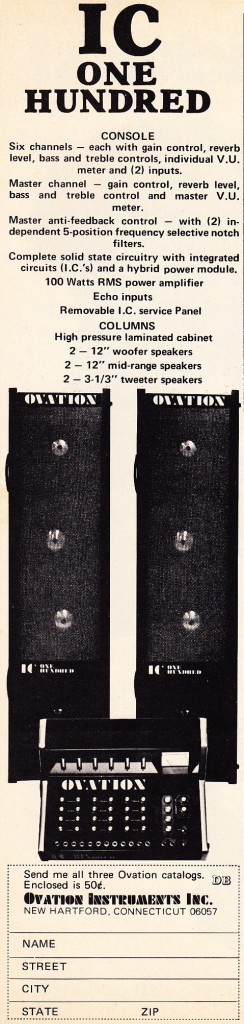

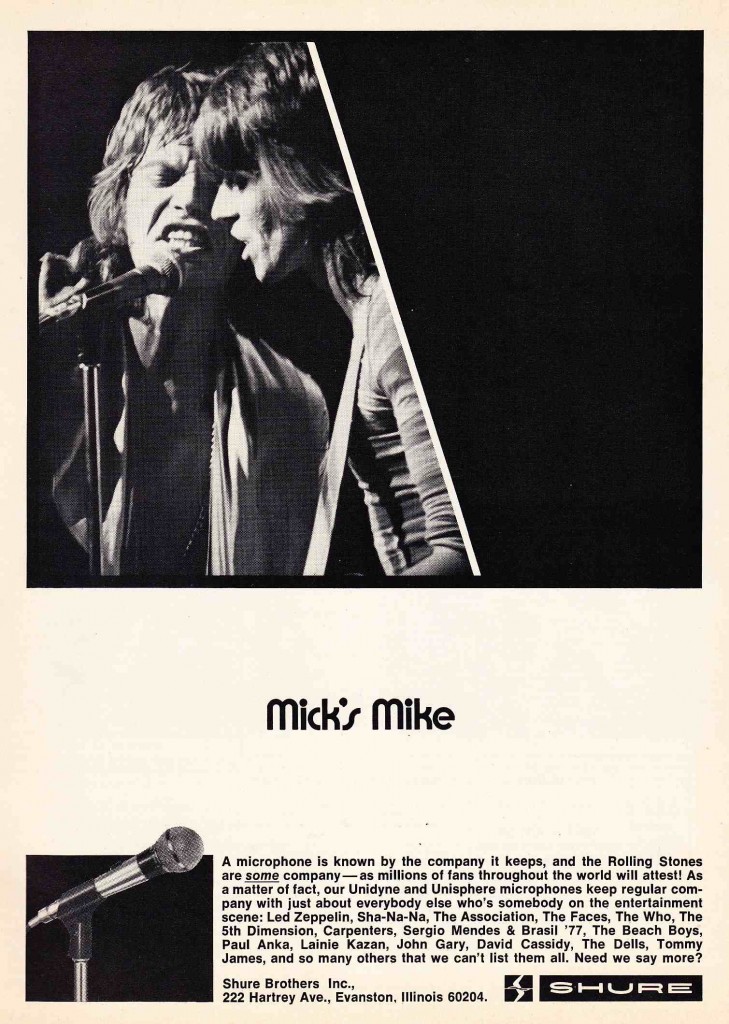

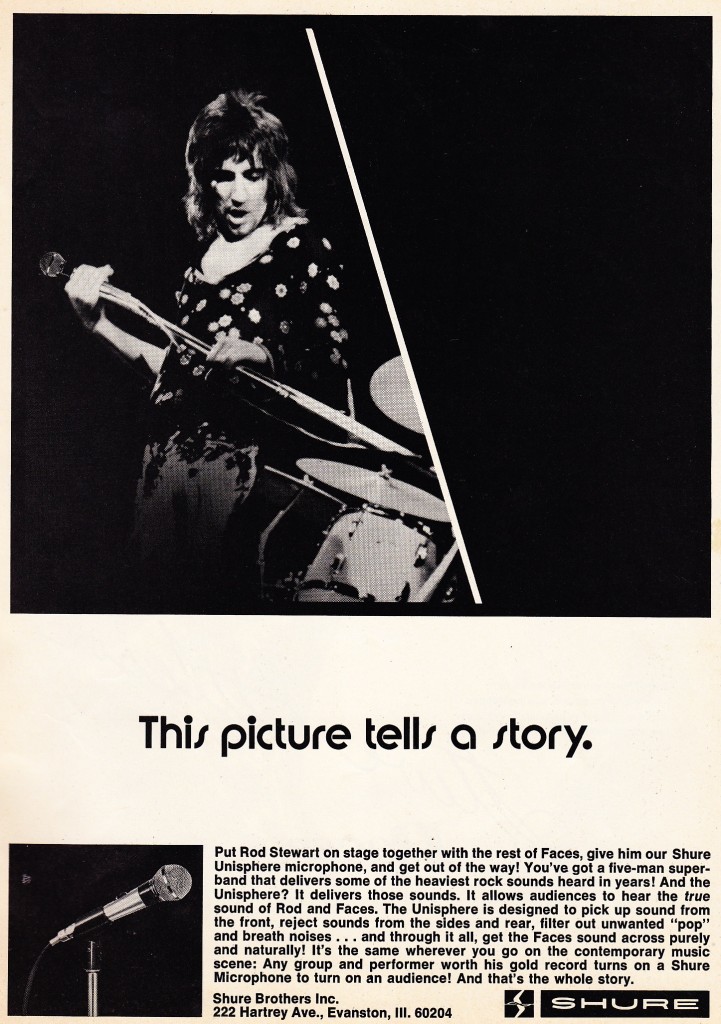

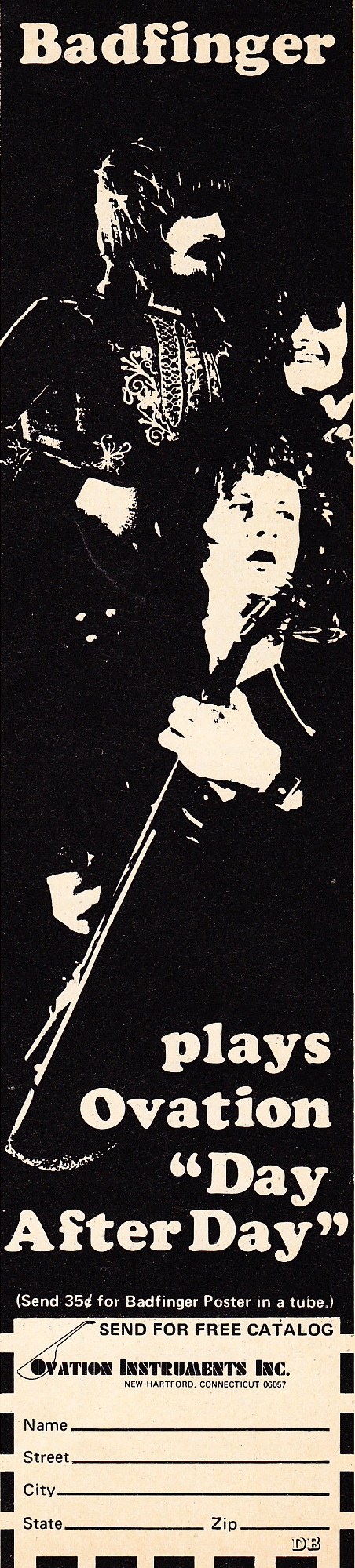

Badfinger endorse the Connecticut-made Ovation acoustic/electric guitar

Badfinger endorse the Connecticut-made Ovation acoustic/electric guitar

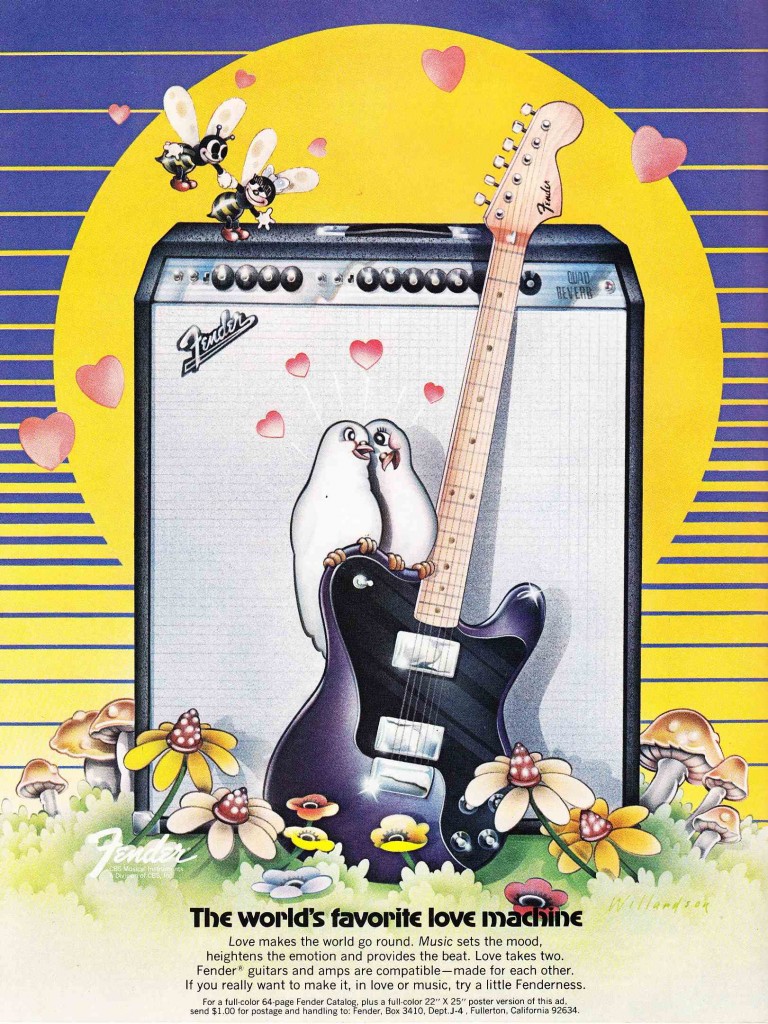

What is it about Ovation guitars that repulses me so? They don’t sound awful. They were made in Connecticut. They are very very circa ’71. I once even saw a video of Thom Yorke in the studio cutting “Exit Music…,” a not-awful song from a not-awful album, with a black Ovation something-or-other. And yet. Faced with the prospect of a playable $40 70’s Ovation at the flea market last week, I passed. God only knows where that $40 went. Just kinda feel like those things are cursed.

What is it about Ovation guitars that repulses me so? They don’t sound awful. They were made in Connecticut. They are very very circa ’71. I once even saw a video of Thom Yorke in the studio cutting “Exit Music…,” a not-awful song from a not-awful album, with a black Ovation something-or-other. And yet. Faced with the prospect of a playable $40 70’s Ovation at the flea market last week, I passed. God only knows where that $40 went. Just kinda feel like those things are cursed.

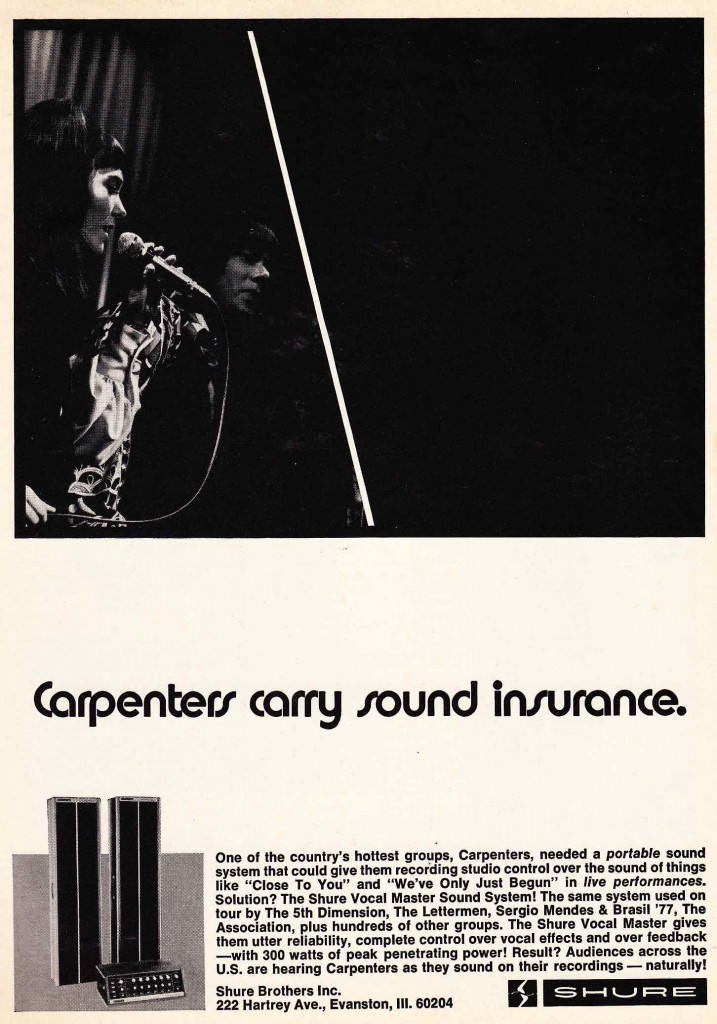

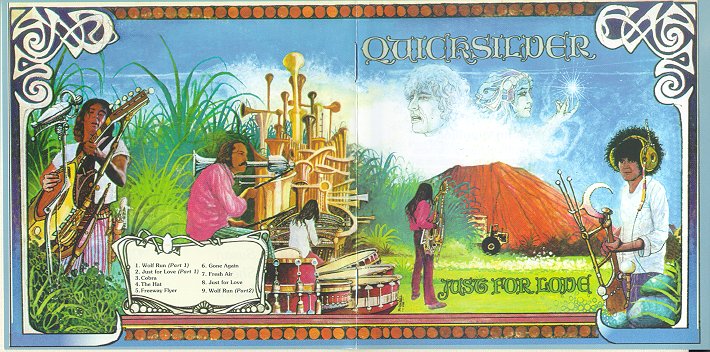

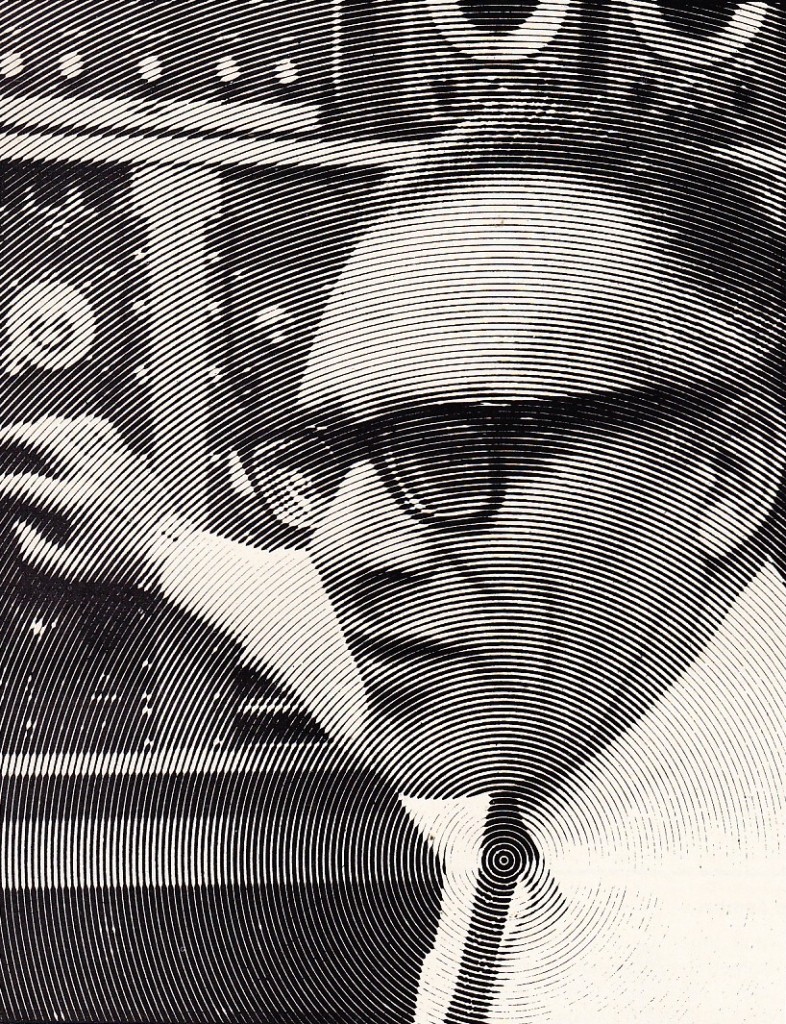

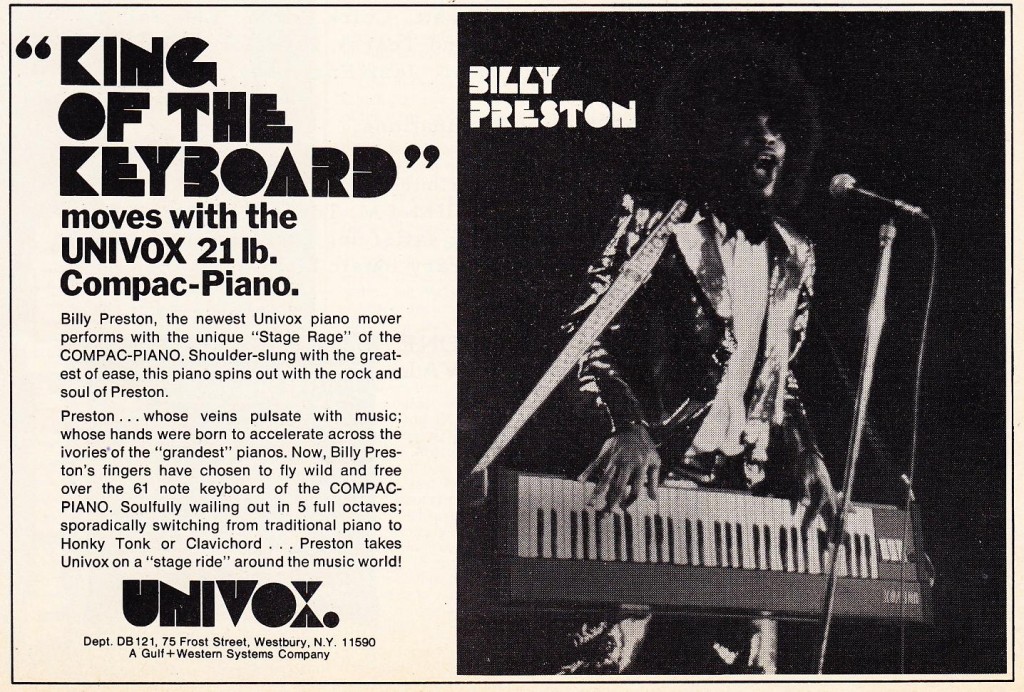

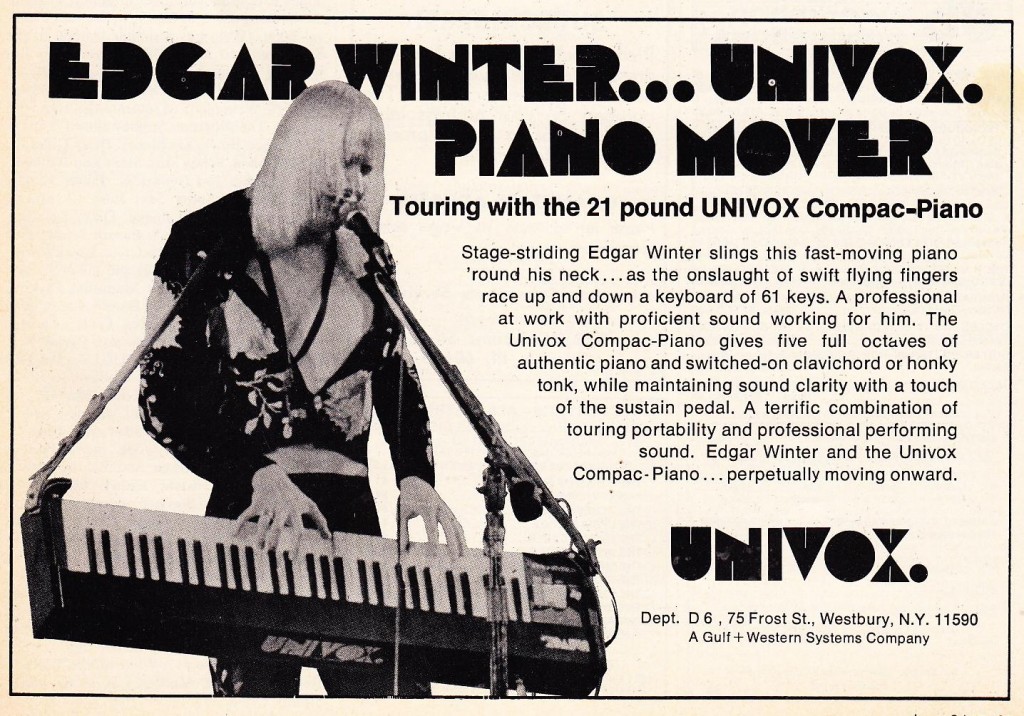

Also cursed: Badfinger! So you’re a band. Shit, you’re a great band. The Beatles sign you to their new record label. Paul writes one of his best-songs-ever for you, and produces the MFkkr. You even go so far as to to pen ‘I can’t live if livin’ is “Without You,”‘ which becomes the defining song of one of the definitive vocalists of the (soon-to-be-over?) era of commercially-sold-recorded-musical-performances. By the end of the decade, two of you have killed themselves and somehow you lost (like, literally, shit, i can’t find it) one million dollars. You are Badfinger.

One of the best rock bands ever.