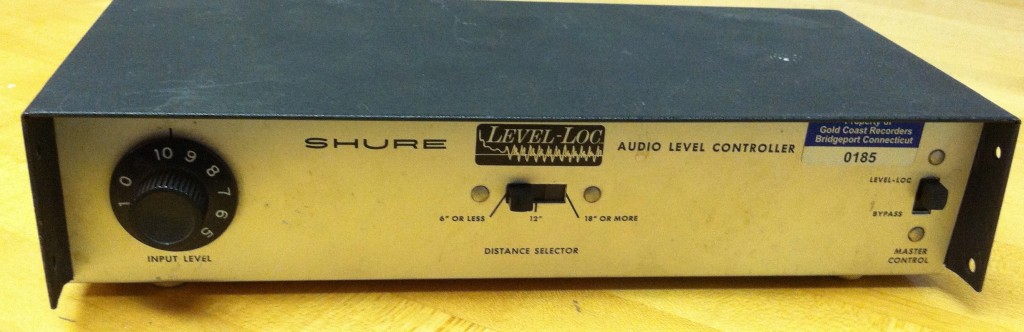

Many of my regular readers will be familiar with the Shure Level-Loc. For those unfamiliar, the basics: the Level-Loc is a brickwall limiter made by the Shure microphone company for public-address-system use (podium mics, specifically) in the 1960s. It uses discrete transistors and transformers in the signal path; it offers balanced mic-level i/o and an unbalanced consumer-level 10K ohm impedance output as well. There is an input-level control (simply a pot that follows that secondary of the input transformer) and a switch marked ‘distance selector,’ which seems to me to be a threshold control. That’s it for control. It is fairly noisy (full-bandwidth noise), even after a recap, and the transformers are not especially well-shielded. It runs off of a 9V battery. For more information on the Level-Loc, you might want to start here.

Anyhow…seems like a toy/piece-of-junk and maybe it is, but these things have become highly coveted for use in recording rock drum performances. How much so? Well, how many other prosumer PA-system pieces are currently available as a plug-in, an API-500 series module, and a boutique re-build? (image source for above)

Anyhow…seems like a toy/piece-of-junk and maybe it is, but these things have become highly coveted for use in recording rock drum performances. How much so? Well, how many other prosumer PA-system pieces are currently available as a plug-in, an API-500 series module, and a boutique re-build? (image source for above)

I recently picked up a clean Shure Level-Loc for a few dollars at a yard sale; after the aforementioned re-cap (and we’re talking about 20 capacitors here…), it was sounding like it was probably operating within its original design parameters. I was intrigued, and figured it might be worth getting it into the racks at Gold Coast Recorders to see what it could do. GCR is a big, live-sounding room, so there’s plenty of sound to get out of it with a squashed compressor. The only potential problem: the Level-Loc offers only mic-level or low-level medium-impedance output. I like to run my mic preamps directly into the Lynx convertors; so for the most direct signal, I would need a bridging amp to bring up the level and lower the impedance of the Level-Loc. It would be nice to have an output level control too, and I wanted the piece to be as physically small as possible so that it could sit directly next to the Level-Loc on a 2RU rack shelf. Here’s what I did to solve all of these problems and fold the Level Loc into the studio alongside all the other outboard mic preamps.

***********************************************

***********************************************

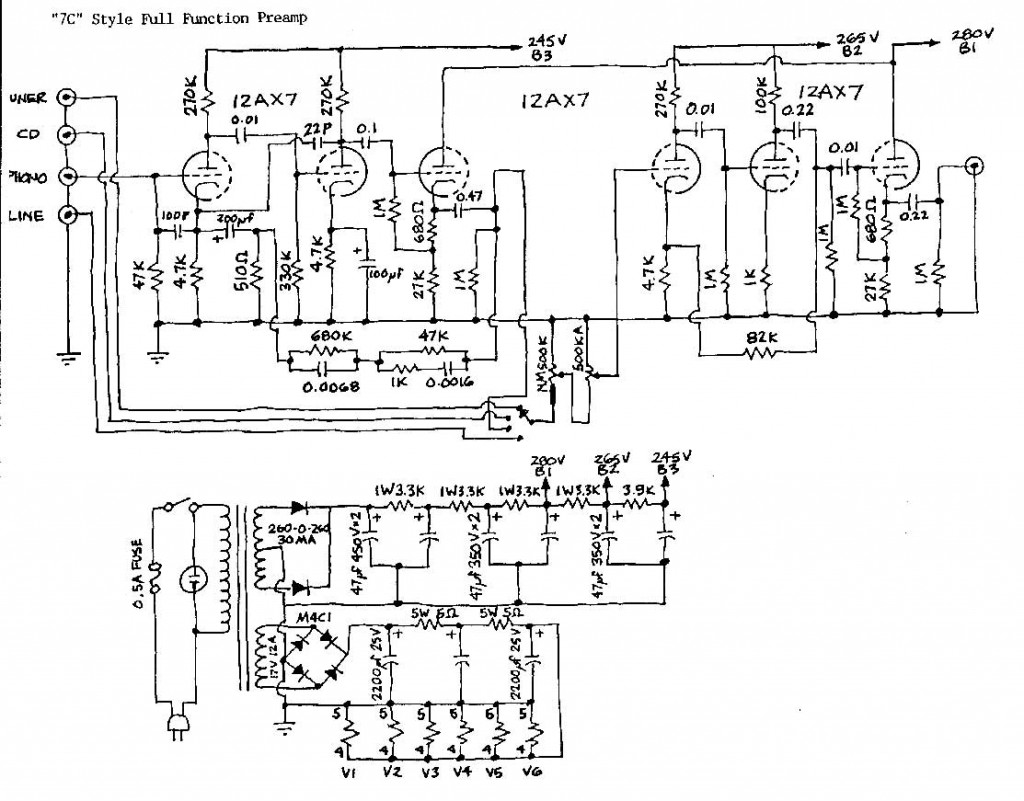

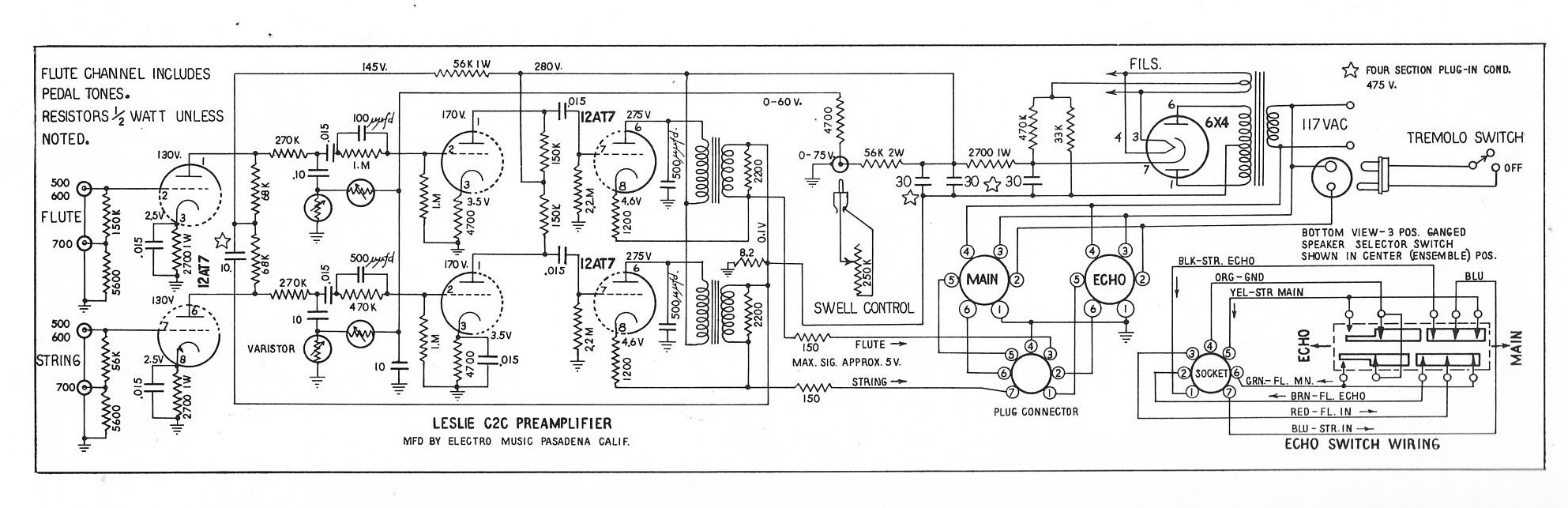

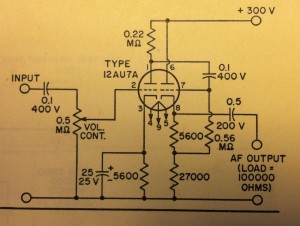

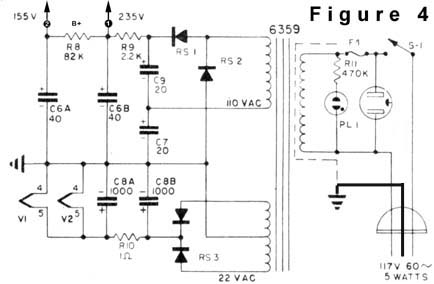

Most of the RCA Receiving Tube manuals have a schematic for some sort of ‘audio input amplifier’; I wanted one that would provide about 20db of gain as well as a very low-impedance output so that I could drive a 15K:600 output transformer easily (I used an NOS UTC Ouncer to save space). Based on this i selected the circuit above RCA manual # RC-24. One 12AU7 tube. Simple, easy. The physically smallest plate/filament transformer that I had on hand was an NOS Stancor 120v:120V/6.3V, so I used the voltage-doubler B+ supply circuit as-found in the Altec 1566 and 438: here is that schematic via Tangible Technology:

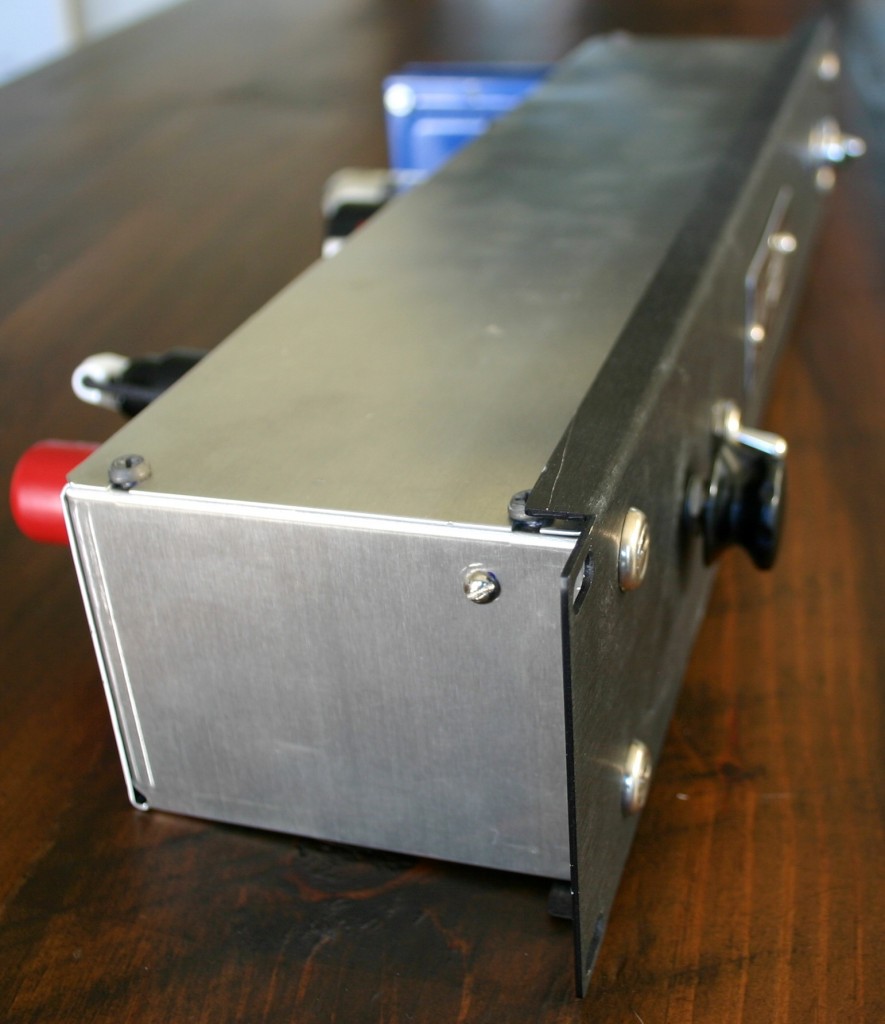

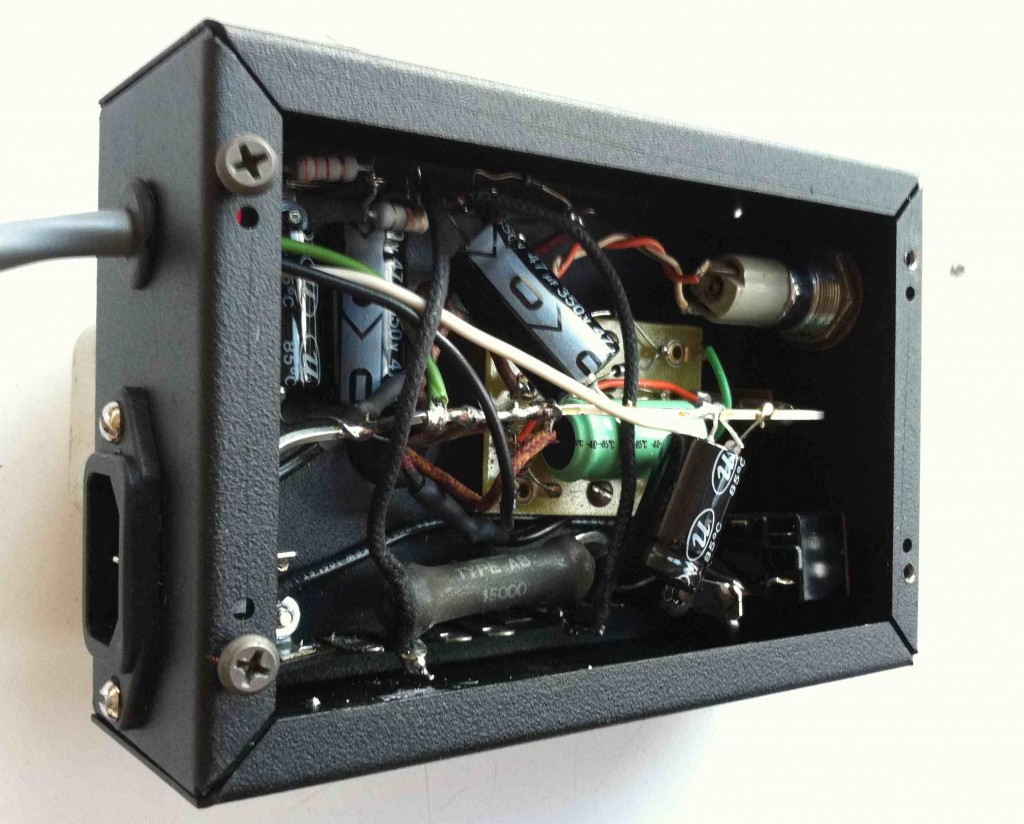

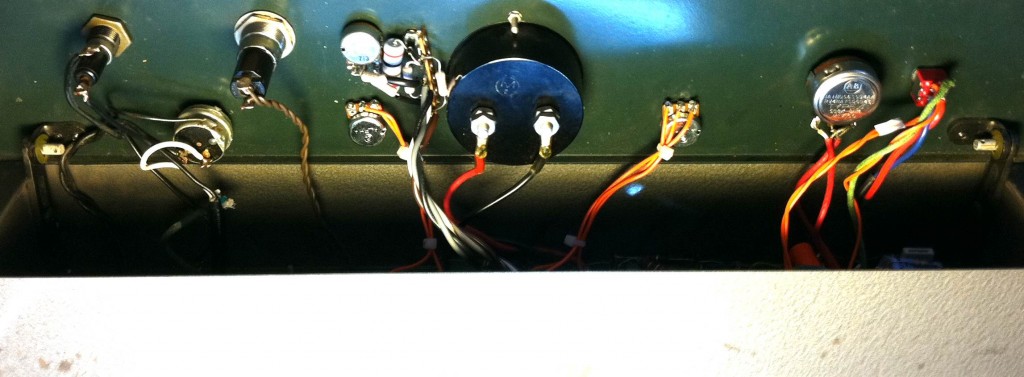

For once i actually did not bother wiring up a DC filament supply, since the gain of the unit is pretty low. This was the right choice, as i can hear no hum at all in the finished unit. I added a 500K pot at the input jack and voila. The whole thing fit inside one of those aluminum Bud Boxes that some folks use for DIY’ing guitar effects pedals. I left the power transformer bolted outside the unit on the rear; it’s always a good idea to keep power transformers away from audio transformers if you can. Here’s the interior of the unit:

For once i actually did not bother wiring up a DC filament supply, since the gain of the unit is pretty low. This was the right choice, as i can hear no hum at all in the finished unit. I added a 500K pot at the input jack and voila. The whole thing fit inside one of those aluminum Bud Boxes that some folks use for DIY’ing guitar effects pedals. I left the power transformer bolted outside the unit on the rear; it’s always a good idea to keep power transformers away from audio transformers if you can. Here’s the interior of the unit:

…and below you can see the finished piece. Not my finest piece of industrial design but it does the job. I put the 1/4″ TS input on the front of the unit so that I can use it as a DI input for Keyboards ETC if the need arises. The circular grill on the top surface of the piece is a heat-vent positioned directly above the 12AU7 tube.

…and below you can see the finished piece. Not my finest piece of industrial design but it does the job. I put the 1/4″ TS input on the front of the unit so that I can use it as a DI input for Keyboards ETC if the need arises. The circular grill on the top surface of the piece is a heat-vent positioned directly above the 12AU7 tube.

The unit performs well, especially considering that there are only two stages of filtering in the power supply. I always use four stages of filtering in the equipment that I build for customers, with at least one choke; I was curious this time to see how the basic Altec B+ scheme worked, though, and it seems just fine! People love their 1566s and 438s so fukk it. Good enough is sometimes good enough…

The unit performs well, especially considering that there are only two stages of filtering in the power supply. I always use four stages of filtering in the equipment that I build for customers, with at least one choke; I was curious this time to see how the basic Altec B+ scheme worked, though, and it seems just fine! People love their 1566s and 438s so fukk it. Good enough is sometimes good enough…

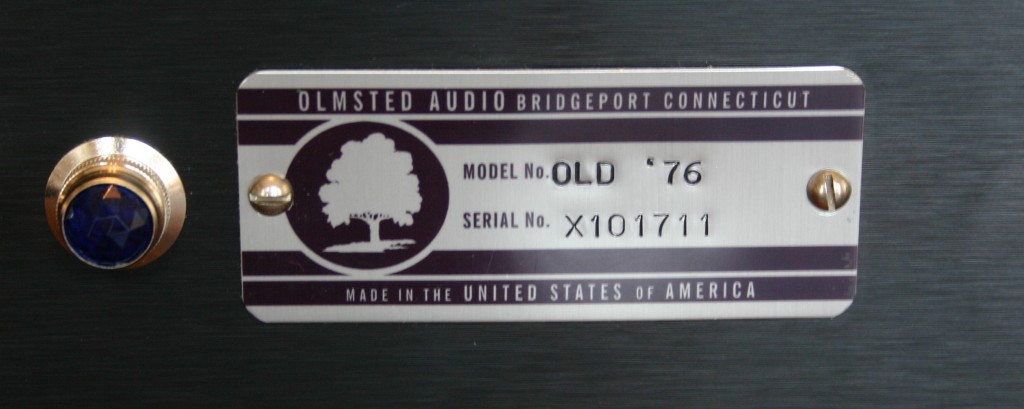

Above, the two units side-by side. So how does it sound? TW and I were putting down live drums on a track at GCR and here’s the result we got.

Above, the two units side-by side. So how does it sound? TW and I were putting down live drums on a track at GCR and here’s the result we got.

First, the drumbeat: close-mics only: CloseOnly

Here’s the same mix, but with the Level Loc signal added: in this case, the Level Loc was amplifying a figure-8 ribbon mic 20 feet from the kit, with the null of the mic facing the kit; the waveform was then re-aligned to eliminate some of the delay: withLevelLoc

And finally, the Level-loc signal only: LevelLocOnly

The Level-Loc is aptly named. Regardless of what you put in – a baby’s breath or an atomic blast – you get the saaaaame level out. Zero dynamics. It’s pretty uncanny. And a great sound for heavy rock drum beats. This is the 2nd track that I have used it on in a week and I think it will continue to get a lot of use at the studio. The output of the balancing amp is a little low – even with the input attenuator all the way open it cannot quite get to full level via the Lynx convertors. It’s good enough, but it could stand to put out a few more DB. If you build one of these devices for use with your Level-loc you might consider using a 15K:60K interstage transformer at the input to get a little bit more level out of it; or re-bias the two stages in order to use a 12AT7 instead of the 12AU7.