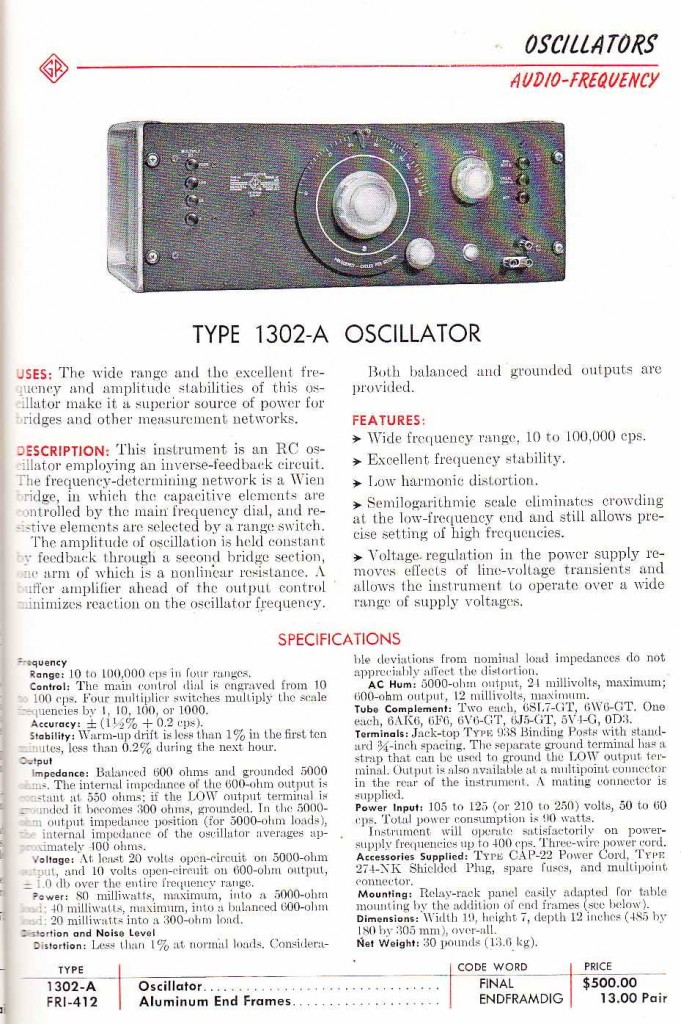

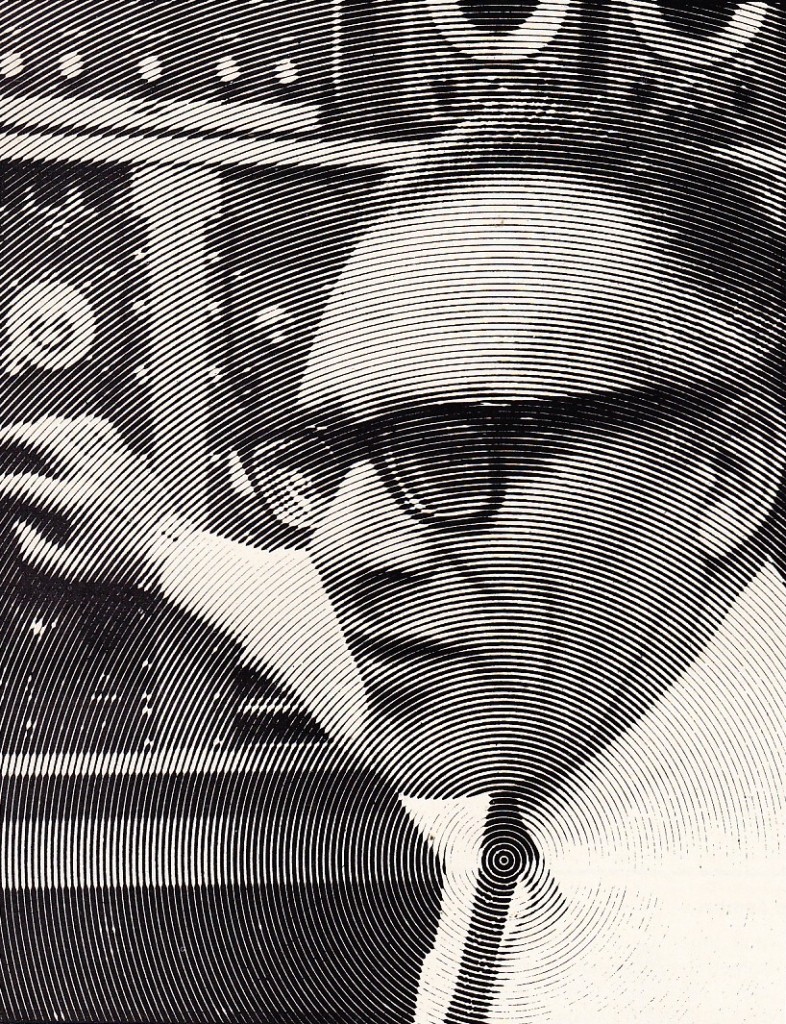

Bach Expert Rosalyn Tureck at-work at the Moog Modular circa 1977. Tureck was a student of Leon Theremin and made her Carnegie Hall debut playing the primitive electronic instrument of his name. (Image: High Fidelity Magazine, 10.77)

Bach Expert Rosalyn Tureck at-work at the Moog Modular circa 1977. Tureck was a student of Leon Theremin and made her Carnegie Hall debut playing the primitive electronic instrument of his name. (Image: High Fidelity Magazine, 10.77)

Category: Early Electronic Music

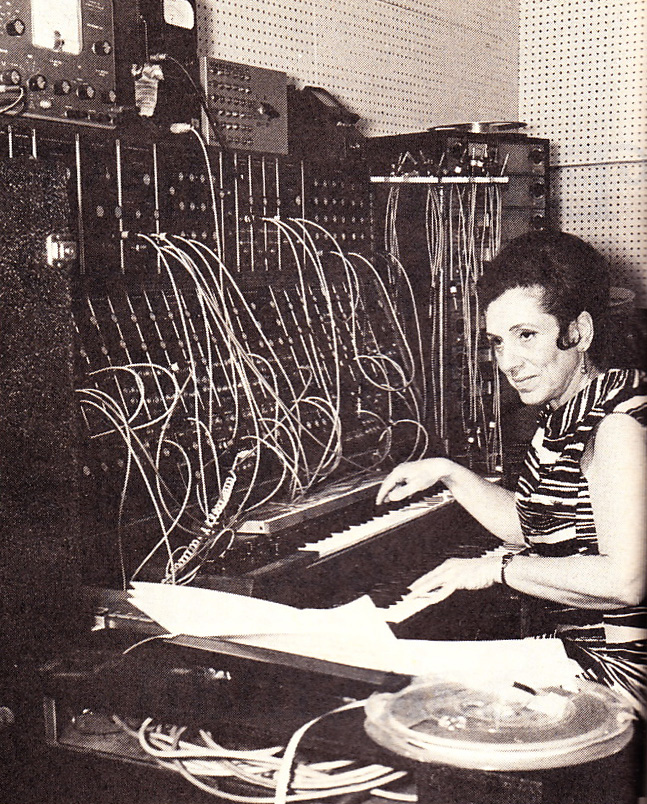

Raymond Scott in his home studio, 1955

Raymond Scott in his home studio, 1955

“The composer must bear in mind that the radio listener does not hear music directly. He hears it only after the sound has passed through a microphone, amplifiers, transmission lines, radio transmitter, receiving set, and, finally, the loud speaker apparatus itself.” —Raymond Scott, 1938

“Raymond Scott was definitely in the forefront of developing electronic music technology, and in the forefront of using it commercially as a musician.” – Bob Moog (SOURCE)

Raymond Scott was one of the true visionaries of early electronic music. You can read his fascinating story here. Being a huge fan of Eno, Tangerine Dream, and Klaus Schulze, it is remarkable to me that Scott was creating very similar compositions (often with his own homemade equipment) a decade or more before any of those artists. Many early electronic artists seemed interested in sound-as-music, noise-as-music – recall how Varese, Stockhausen, and Luening used electronics in their work. Others seemed content to replicate traditional harmonic and melodic patterns, using the newly available electronic voices as novel colors. For instance, Wendy Carlos (no link available due to the fact that Carlos seems stuck in the past as regards YouTube and modern content realities. Ironic, ain’t it). NEways,,, Scott, contrary to both of these approaches, walked a middle line – creating often wholly electronic music in which the harmonic, rhythmic, and melodic strategies were both pleasantly listenable but also very true to their synthetic nature: there’s really no attempt to shoehorn trumpet and piano lines into the new voices he established. To rephrase: the material is very much composed for these particular new voices, but in an approachable way.

Above, Scott’s ‘Electronium’ music computer of 1965. Not too surprisingly, it is currently owned by Mark Mothersbaugh; a child to Scott’s marriage of esoteric electronics and pop sensibility if there was ever one. The ‘Electronium’ currently awaits restoration. Makes me cringe to just think about servicing that thing. Good luck fellas.

Above, Scott’s ‘Electronium’ music computer of 1965. Not too surprisingly, it is currently owned by Mark Mothersbaugh; a child to Scott’s marriage of esoteric electronics and pop sensibility if there was ever one. The ‘Electronium’ currently awaits restoration. Makes me cringe to just think about servicing that thing. Good luck fellas.

For more coverage of early electronic music pioneers on PS dot com, click here.

When you think of ‘early electronic instruments,’ what period comes to mind? European tape music of the 1950s? Academic electronic music labs of the 1960s? How about 1931?

When you think of ‘early electronic instruments,’ what period comes to mind? European tape music of the 1950s? Academic electronic music labs of the 1960s? How about 1931?

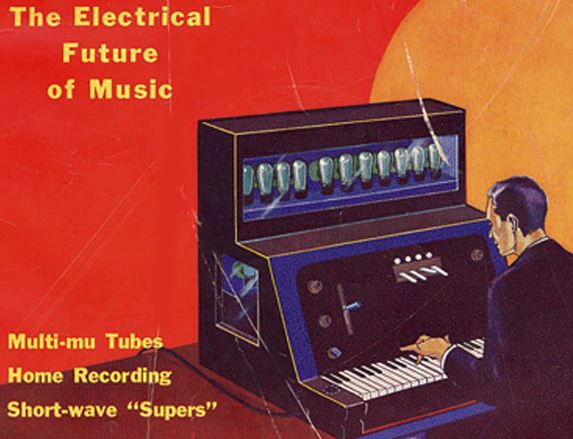

Download a five-page article from Radio News 1931, on ‘The Electrical Future Of Music.’

Download a five-page article from Radio News 1931, on ‘The Electrical Future Of Music.’

DOWNLOAD: Radio_News_3107_Electronic_Music

It’s interesting to see her how the focus is primarily on the creation of instruments on which one could perform western tempered music (as opposed to music concrete or noise-music). Although those more avant garde approaches to electronic music would come soon, this earlier approach – the electronic (as opposed to bellows) organ, the violin-simulating theremin – seems to be what has won out. Eighty years later, most of us are not usually listening to atonal clusters of carefully organized noise – we’re still mostly listened to very diatonic, 4/4 folk-songs (essentially) performed and presented via wholly electronic means.

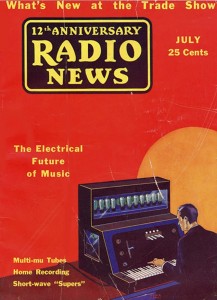

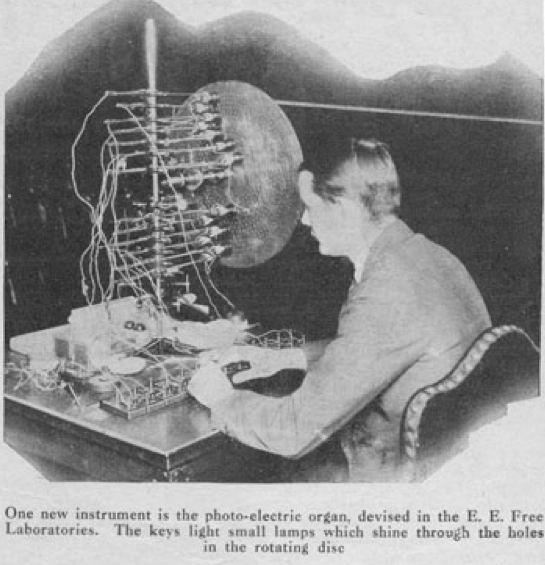

Above: the photo-electric organ

Above: the photo-electric organ

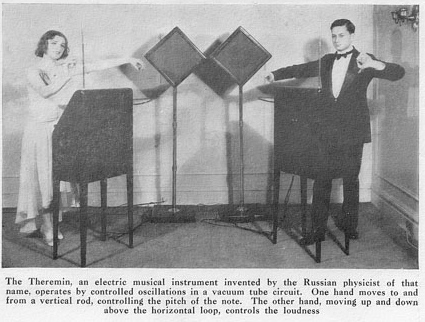

Above: the Theremin, still popular today in a variety of musical genres.

Above: the Theremin, still popular today in a variety of musical genres.

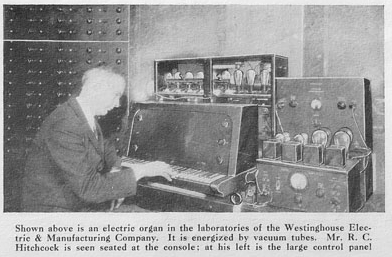

Above: an electronic organ built by Westinghouse, 1931.

Above: an electronic organ built by Westinghouse, 1931.

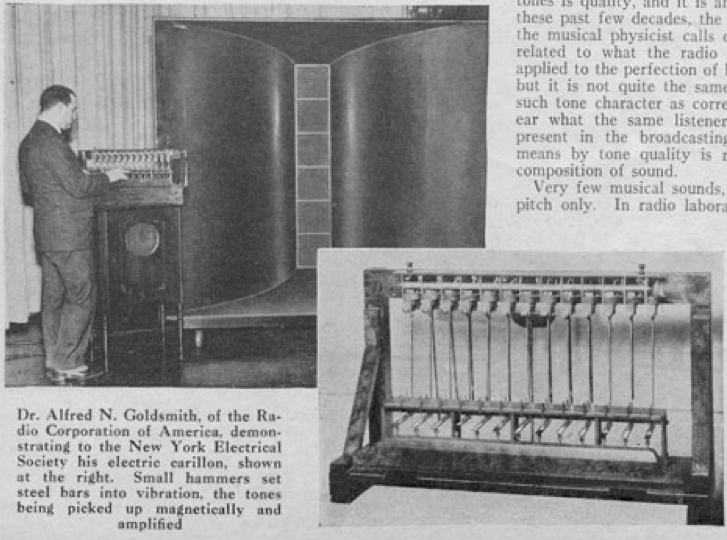

Above: an electronic Carillion as built by RCA. The principle employed here is also still very popular today.

Above: an electronic Carillion as built by RCA. The principle employed here is also still very popular today.

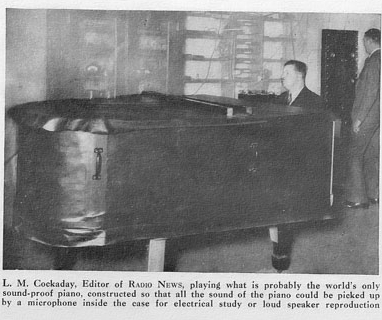

Early attempt at acoustic isolation of an instrument for electronic pickup

Early attempt at acoustic isolation of an instrument for electronic pickup

It never ceases to amaze me how many people navigate to this website as a result of searching for Magnecord tape-machine information. Until I bought a pair of PT6 machines last year, I had no awareness of them; since then, I am continually discovering more and more evidence of the role that Magnecord played in mid-twentieth century broadcasting and recording in the United States. Moreover, my two machines (previously owned by the University of Connecticut; purchased by me last year for $25/each) now work great after I performed some restoration work. This is no mean feat for sixty-year-old tape recorders which were subjected to the harsh treatment of student-recordists for untold decades. Anyhow, you can hear some early test-recordings that I made with the PT6 shortly after I restored them: listen here and here. Since I recorded that version of “Hallelujah,” my two PT6’s have been parked in the entryway of our studio Gold Coast Recorders. Clients often inquire about them, surprised to learn that they are in fact functional; but it was not until last week that they actually got used on a session. Take a listen to the track below and you can hear some of the wonderful music of Keith Restaurant. Keith’s been a frequent visitor to Gold Coast since we opened our doors in April and he makes music that you might call minimalist, or noise music, or process music; it’s inherently impossible to categorize. With this sort of ‘organized sound,’ every listener needs to find his/her own way in. The following piece is from a set he recorded called ‘computer music.’ You are hearing a single live take of several performers manipulating the harddrives and power supplies of live laptop computers, amplified with induction mics and guitar amplifiers. The Magnecord PT6 is the primary recording medium, and several generations of re-amping and re-tracking (via our UREI 809 studio playback monitors) in the big live room at Gold Coast were layered to create the overall piece.

It never ceases to amaze me how many people navigate to this website as a result of searching for Magnecord tape-machine information. Until I bought a pair of PT6 machines last year, I had no awareness of them; since then, I am continually discovering more and more evidence of the role that Magnecord played in mid-twentieth century broadcasting and recording in the United States. Moreover, my two machines (previously owned by the University of Connecticut; purchased by me last year for $25/each) now work great after I performed some restoration work. This is no mean feat for sixty-year-old tape recorders which were subjected to the harsh treatment of student-recordists for untold decades. Anyhow, you can hear some early test-recordings that I made with the PT6 shortly after I restored them: listen here and here. Since I recorded that version of “Hallelujah,” my two PT6’s have been parked in the entryway of our studio Gold Coast Recorders. Clients often inquire about them, surprised to learn that they are in fact functional; but it was not until last week that they actually got used on a session. Take a listen to the track below and you can hear some of the wonderful music of Keith Restaurant. Keith’s been a frequent visitor to Gold Coast since we opened our doors in April and he makes music that you might call minimalist, or noise music, or process music; it’s inherently impossible to categorize. With this sort of ‘organized sound,’ every listener needs to find his/her own way in. The following piece is from a set he recorded called ‘computer music.’ You are hearing a single live take of several performers manipulating the harddrives and power supplies of live laptop computers, amplified with induction mics and guitar amplifiers. The Magnecord PT6 is the primary recording medium, and several generations of re-amping and re-tracking (via our UREI 809 studio playback monitors) in the big live room at Gold Coast were layered to create the overall piece.

LISTEN: KR_CmptrMx_Track2.mp3

Since the sounds that composer Keith Restaurant organize in this music have essentially no reference point (I.E., none of them are sounds that you or I would have heard before), every element of the production process is incredibly important in creating meaning. In this way, the Magnecord PT6, with it’s peculiar frequency response, distortions, and flutter, is being used in a very significant way; it is a primary component of the sound, rather than an ‘effect.’ This contribution is intensified by the multiple-generations of recording and re-recording via the PT6. It is also interesting to note than even in the longer (4:00) piece, the PT6 deviated less than 250ms over 4:00 relative to the Pro Tools safety copy. This is great news for anyone who wants to fold one of these into their working process.

You can learn more about Keith Restaurant at his blog.

“Does this qualify me for a prophet? Well, perhaps partially.”

“Does this qualify me for a prophet? Well, perhaps partially.”

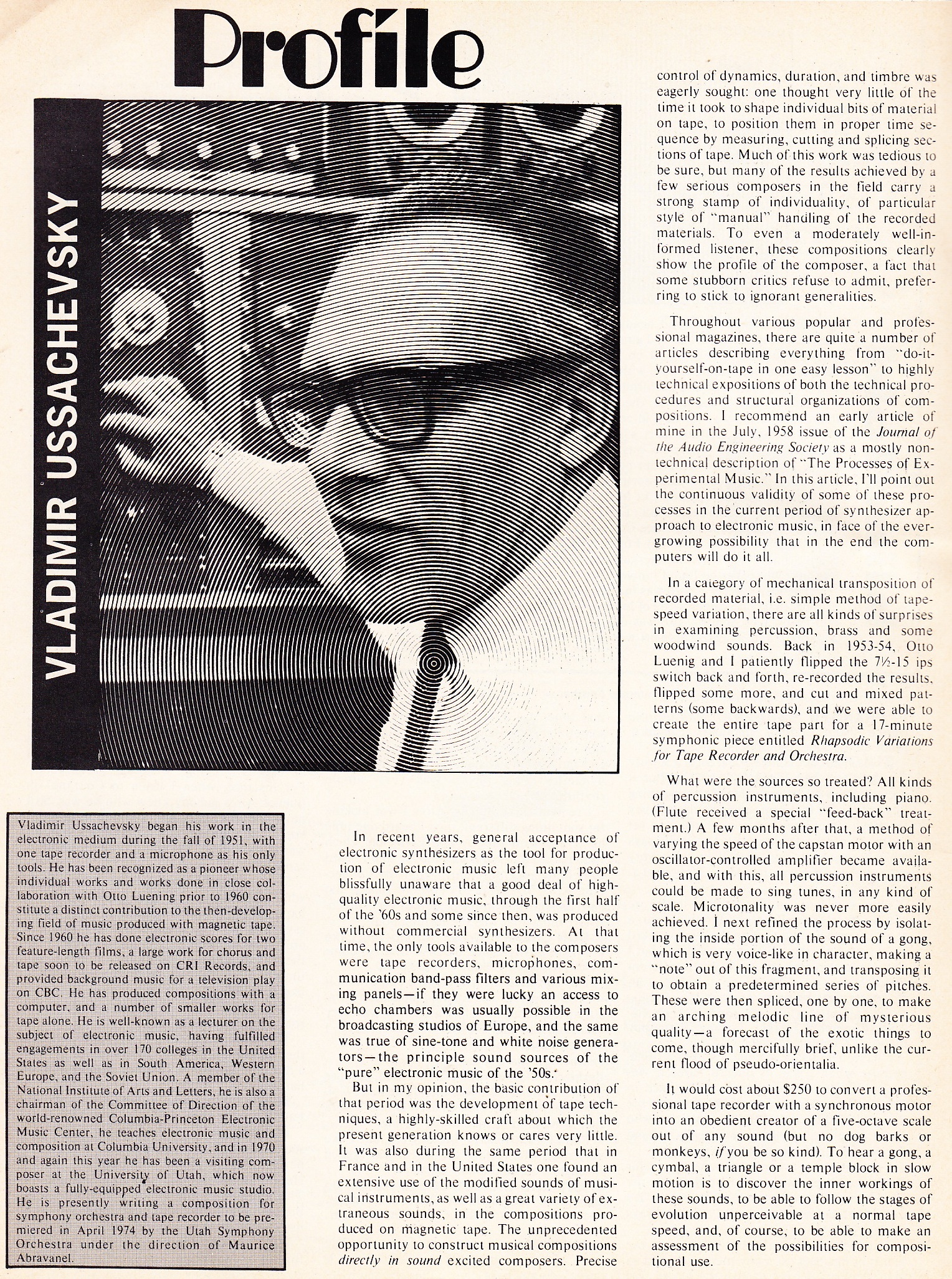

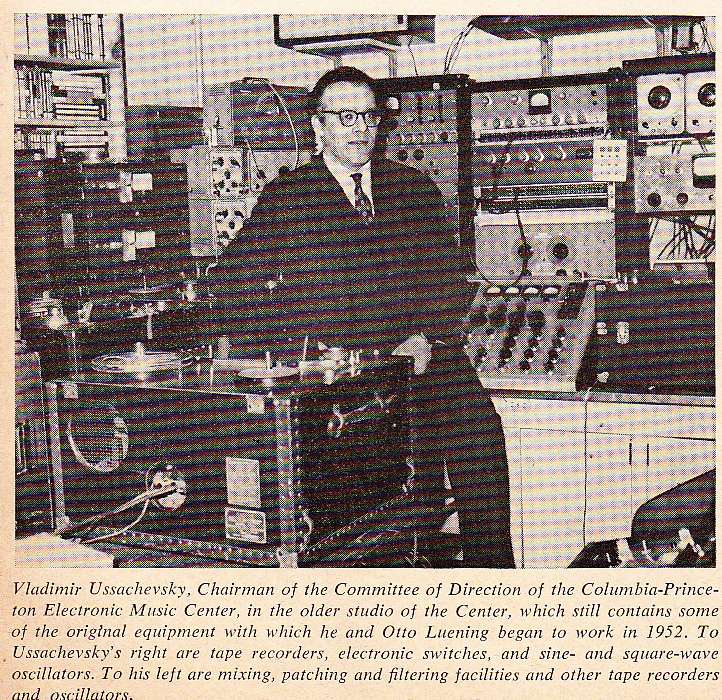

Imagine if this dude had been your college music professor. Read a 4-page essay by Mongolian-born composer Vladamir Ussachevsky as printed in the 1/17/74 issue of DOWNBEAT magazine. Ussachevsky was one of the founders of the legendary Columbia-Princeton electronic music studio, and one of the folks who bridged the tape-manipulation and synthesizer eras of early electronic music. It’s almost impossible for us to grasp the conceptual leaps that these early pioneers had to make in order to arrive the formulation of audio-manipulation-as-music; for many of us working as musicians in the past few decades, it’s hard to even separate music and audio, so intertwined is audio technology with music, so thoroughly has the studio become-an-instrument.

Follow the link to READ ON…

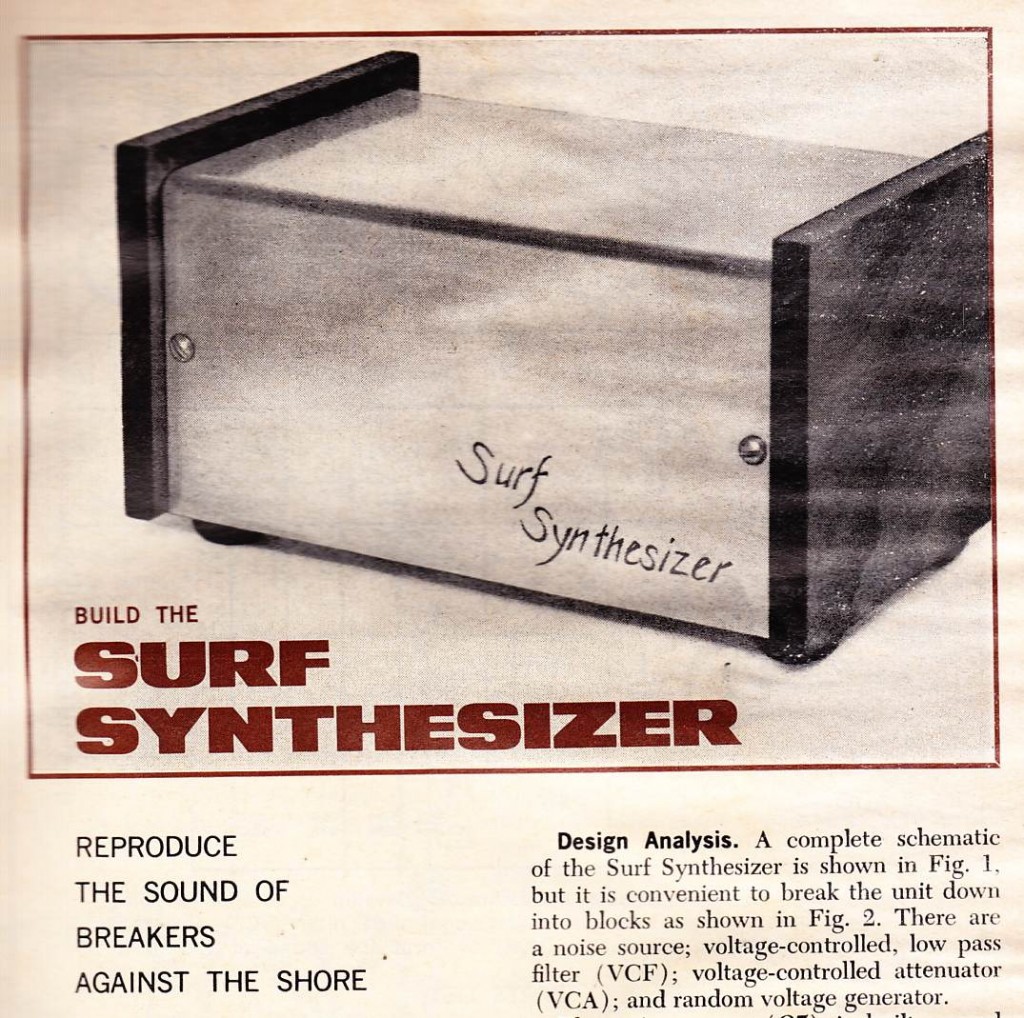

Download a five-page article by David L. Heiserman on “Music Synthesizers And How They Work” from Popular Electronics magazine, February 1972. Also included is a brief description and schematic for a ‘surf synthesizer’ project.

Download a five-page article by David L. Heiserman on “Music Synthesizers And How They Work” from Popular Electronics magazine, February 1972. Also included is a brief description and schematic for a ‘surf synthesizer’ project.

DOWNLOAD: SynthsPopElecFeb1972

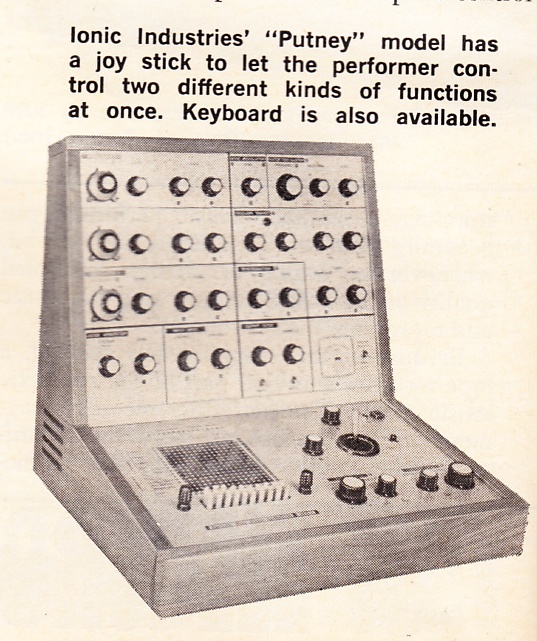

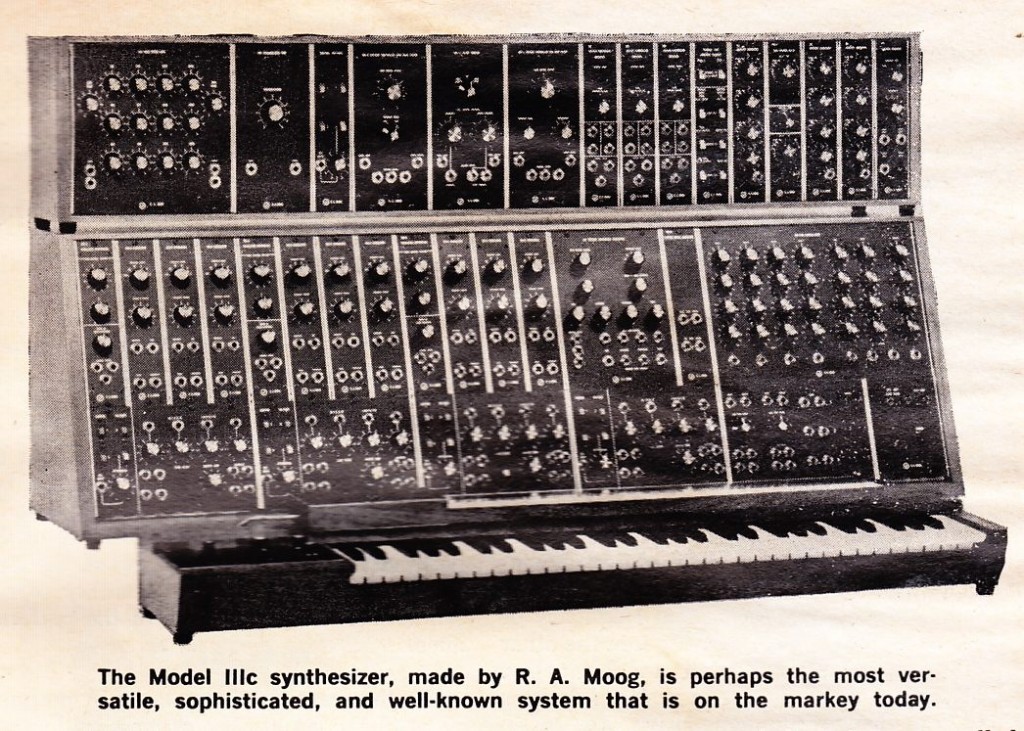

Nice images of the Putney Synth and a Moog IIIc. This article offers a very broad treatment of the subject, and it does not discuss music or music aesthetics very much; it is interesting though because it is intended for an audience with some technical savvy. Everything in this piece can easily be applied to gaining a greater fluency with the software synths that we use today.

Nice images of the Putney Synth and a Moog IIIc. This article offers a very broad treatment of the subject, and it does not discuss music or music aesthetics very much; it is interesting though because it is intended for an audience with some technical savvy. Everything in this piece can easily be applied to gaining a greater fluency with the software synths that we use today.

Naturally, any discussion of ‘music-synthesizers’ in Popular Electronics had to be followed by some sort of audio-synthesizer project; since this is 1972, the project is a Surf Synthesizer, aka a white-noise generator followed by a randomly-modulated low pass filter in sync with a VCA. If you know what any of that means, you might could be interested in the schematic, which you can find after the link below. I can imagine sitting at the kitchen table during the Nixon administration, carefully soldering this mood-enhancer while my wife macrames an Owl.

Naturally, any discussion of ‘music-synthesizers’ in Popular Electronics had to be followed by some sort of audio-synthesizer project; since this is 1972, the project is a Surf Synthesizer, aka a white-noise generator followed by a randomly-modulated low pass filter in sync with a VCA. If you know what any of that means, you might could be interested in the schematic, which you can find after the link below. I can imagine sitting at the kitchen table during the Nixon administration, carefully soldering this mood-enhancer while my wife macrames an Owl.

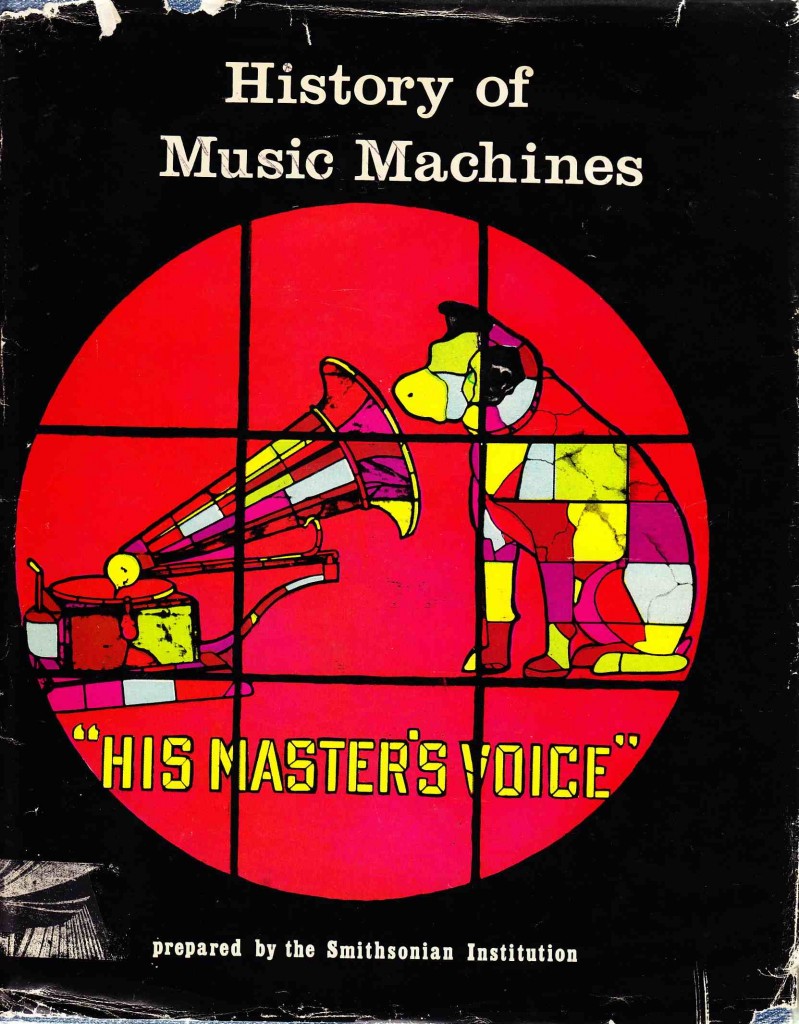

Came across this obscure volume in a rubbish bin several years ago. Published by Drake Publishers in 1975 and billed as being ‘Prepared By The Smithsonian’ (No author attributed), “(The)History Of Music Machines” (hf. ‘HOMM’) is a b&w hardcover gift/coffee-table book which presents a fairly interesting survey of the history of reproduced sound. Several copies are available for just a few bucks at amazon. 139pp.

Came across this obscure volume in a rubbish bin several years ago. Published by Drake Publishers in 1975 and billed as being ‘Prepared By The Smithsonian’ (No author attributed), “(The)History Of Music Machines” (hf. ‘HOMM’) is a b&w hardcover gift/coffee-table book which presents a fairly interesting survey of the history of reproduced sound. Several copies are available for just a few bucks at amazon. 139pp.

From the introduction (by writer Irving Kolodin):

From the introduction (by writer Irving Kolodin):

“Over the years, the debates have continued about the pros and cons of music machines, the impact of their existence on the habit patterns of society,…. their influence for good and evil on taste… As for taste, it has been driven to the wall, and all but through it, by exploitation of the music machines’ potential for serving the lowest common denominator. Whether in records, or in radio’s reliance on the Top Forty -those loudest, hardest, often cheapest appeals to the beetle-browed- selectivity has since foundered on the rock of commercialism.”

Jesus Irving. Don’t mince words buddy. Tell us how you really feel. Note how he allusively slips ‘Be(e/a)tle’ and ‘Rock’ in there. Nice one. ANYhow. Reactionary sentiments asides, HOMM is basically a chronological series of photos with explanatory captions. I find it interesting because it does not attempt to parse recording devices, electric instuments, synthesizers, amplification equipment, choosing instead to include all of these very different (in my mind, at least) type of equipment into the totality of ‘music machines.’ This suggests the view point that music is either made ‘by man alone’ or somehow made ‘by machine.’ It’s an interesting idea. A very outmoded binary opposition, certainly. Here are some highlights.

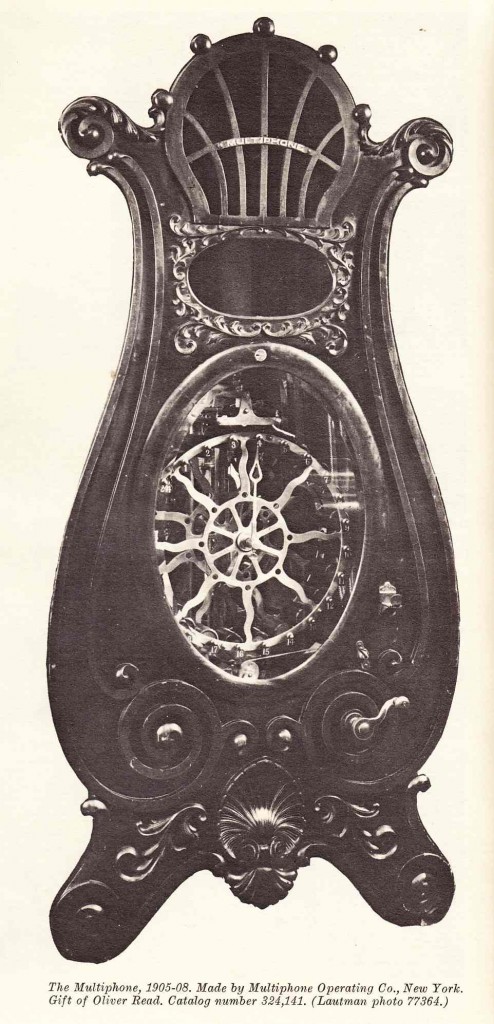

The multiphone, a wax-cylinder jukebox from 1905.

The multiphone, a wax-cylinder jukebox from 1905.

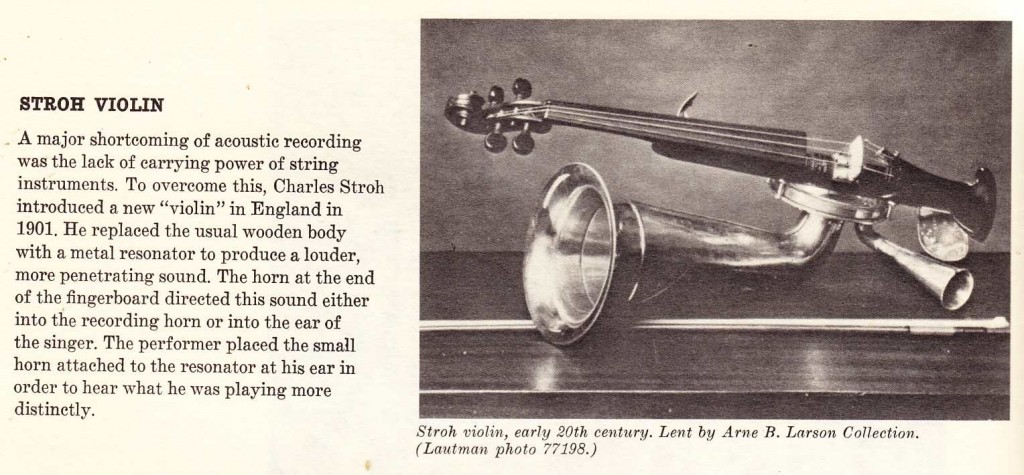

The Stroh Violin. DS mentioned last week that he had seen a band in NYC recently that performs exclusively 1900-1930 music on all period instruments. ‘One of those Violins with the victrola horn’ is apparently employed. Now we know that this is called a Stroh Violin.

The Stroh Violin. DS mentioned last week that he had seen a band in NYC recently that performs exclusively 1900-1930 music on all period instruments. ‘One of those Violins with the victrola horn’ is apparently employed. Now we know that this is called a Stroh Violin.

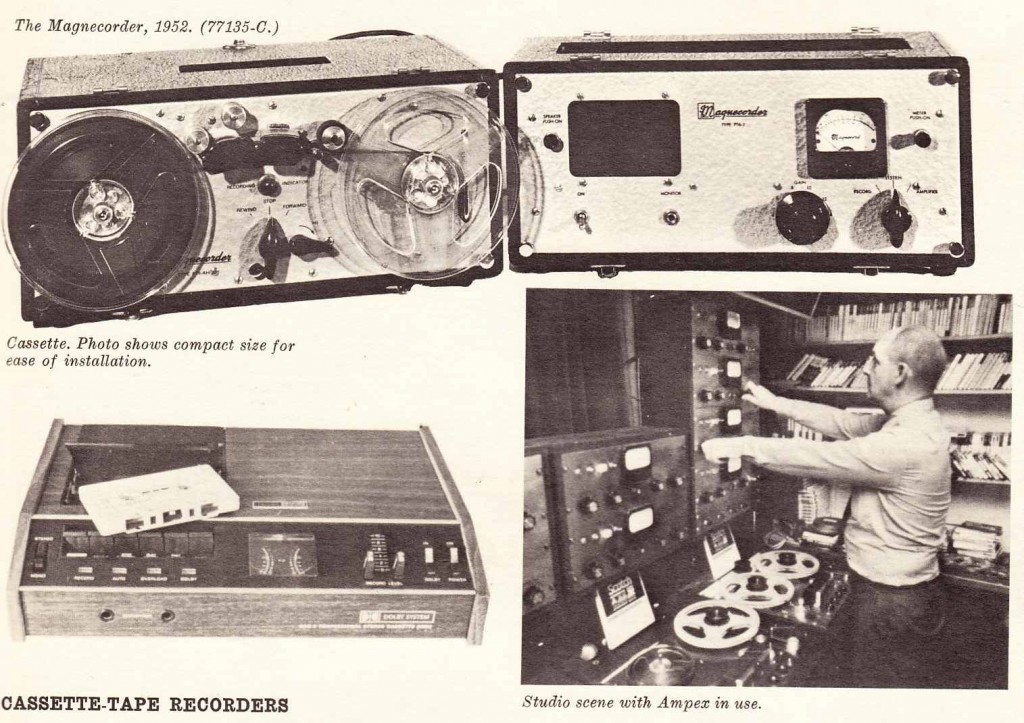

The much-loved Magnecord PT6 gets some praise.

The much-loved Magnecord PT6 gets some praise.

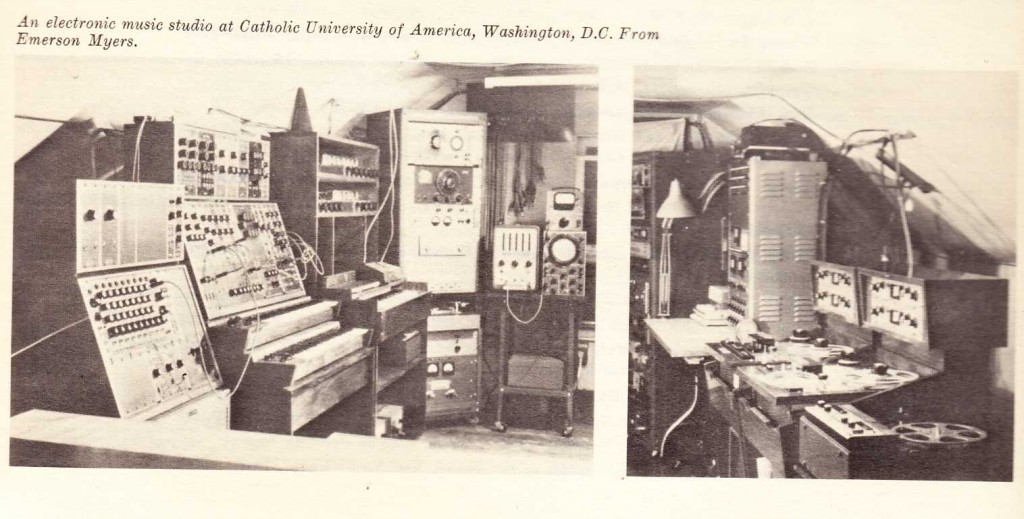

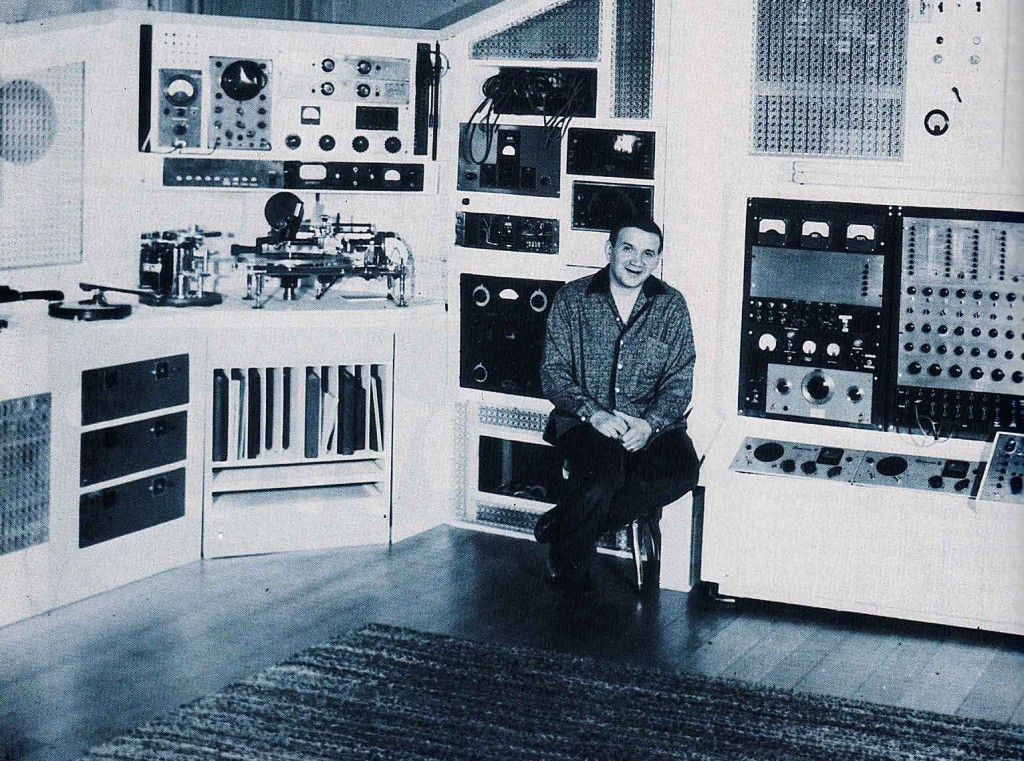

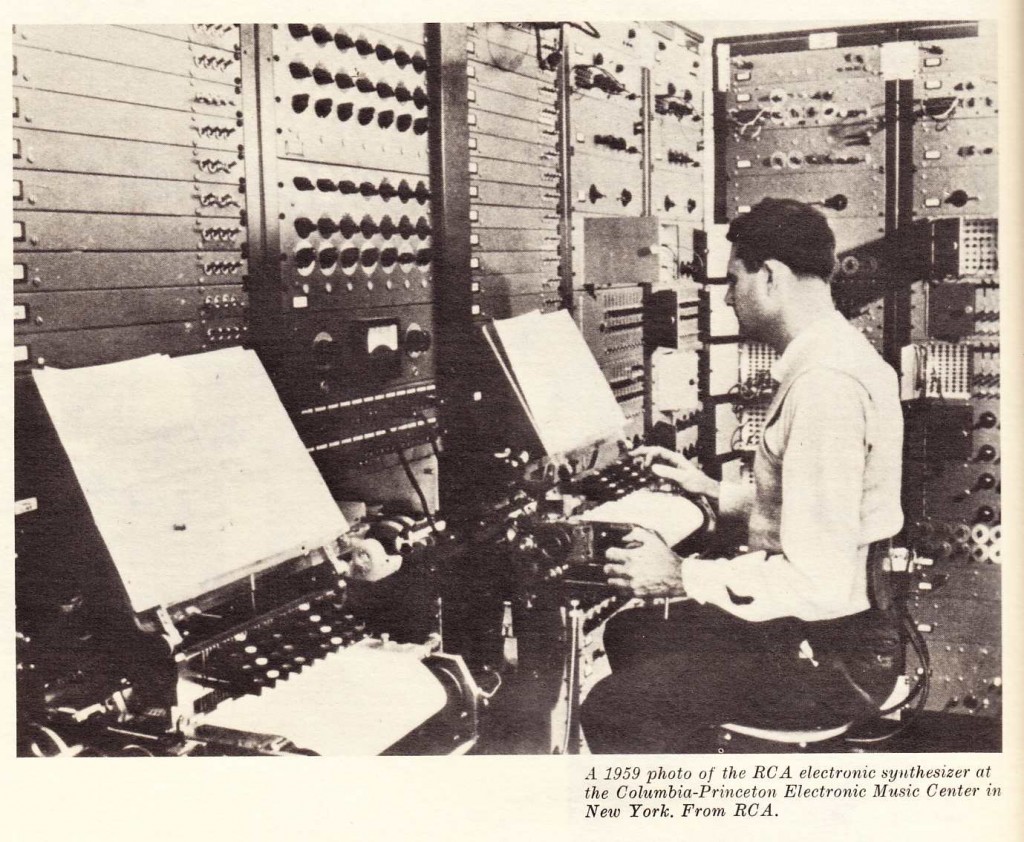

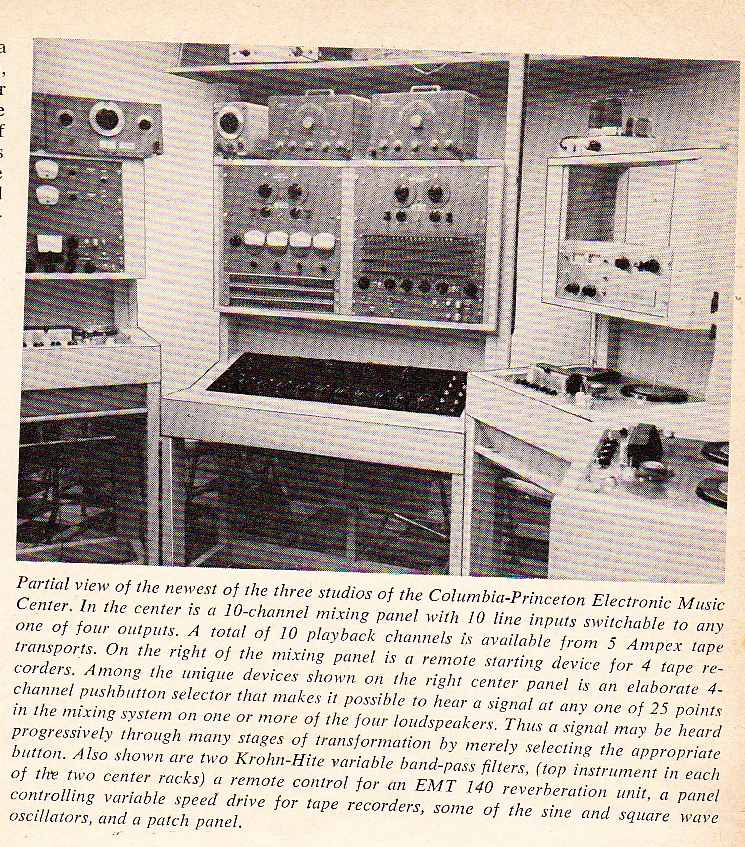

HOMM ends with some (even then very-dated) images of Electronic Music Studios. Above we have the Columbia-Princeton Studio circa 1959 (see my previous post) and below some rare images of the circa ’65 studios at the Catholic University of America.

HOMM ends with some (even then very-dated) images of Electronic Music Studios. Above we have the Columbia-Princeton Studio circa 1959 (see my previous post) and below some rare images of the circa ’65 studios at the Catholic University of America.

(footnote: a nod to EKL, originator of the ‘out-of-print-book-report’ in her PARFAIT series)

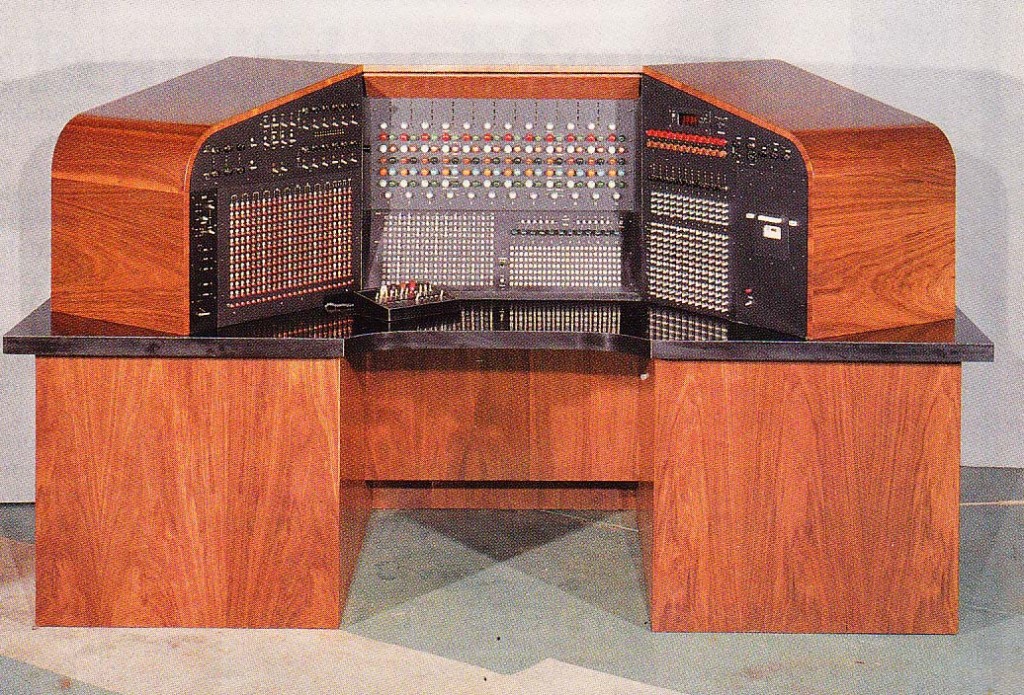

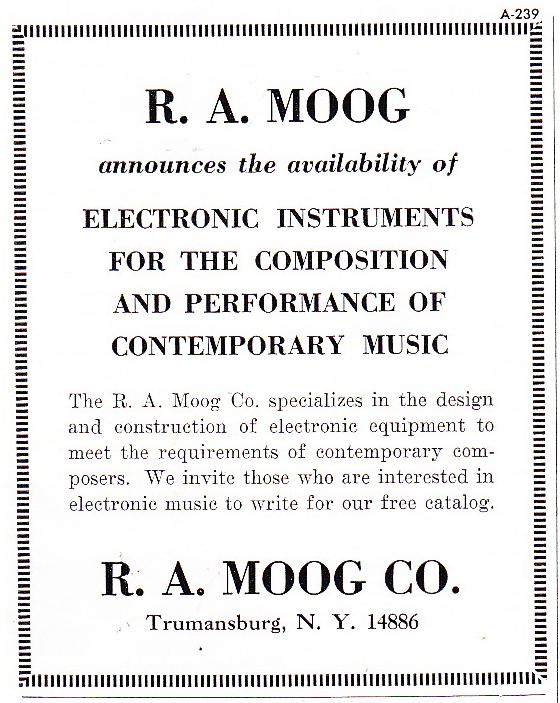

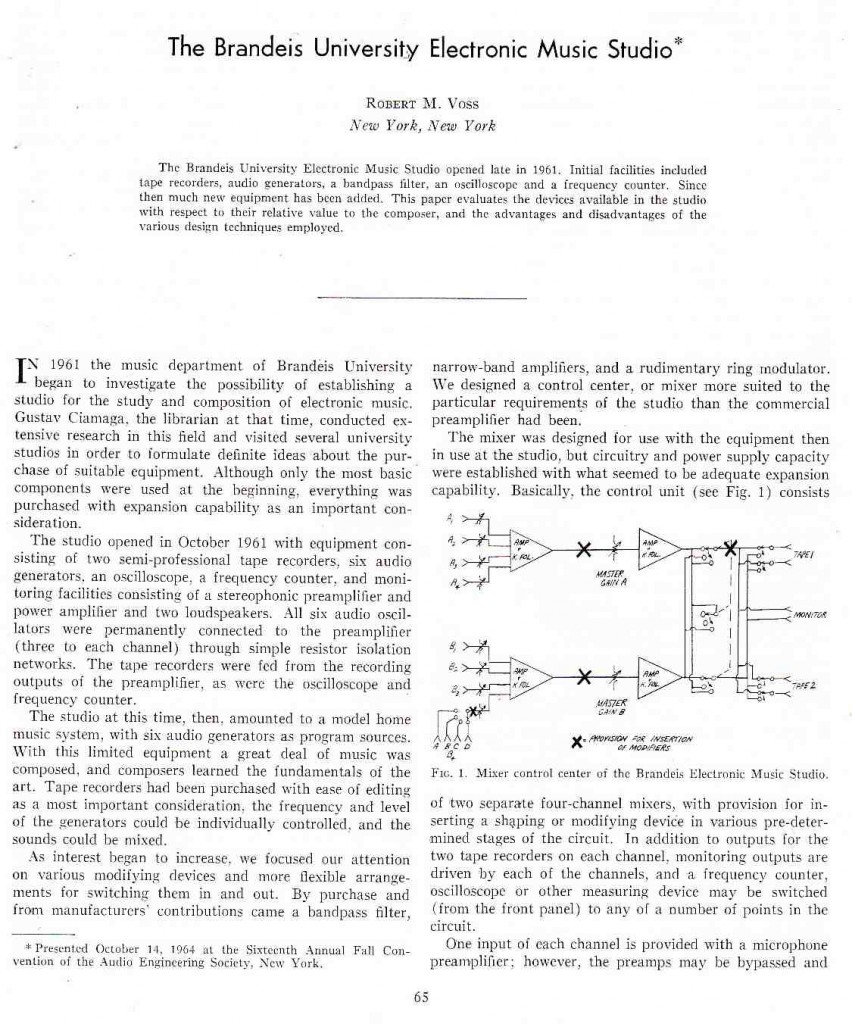

From the back-pages of the AES Journal in 1965:

Moog is a legendary name in the world of music. As far as manufacturers/innovators of musical/audio equipment go, Robert Moog is a close to a household name as anyone I can think of. The original Moog Modular Synthesizer, as used in early ‘hit’ electronic records such as Carlos’ “Switched on Bach,” was the earliest commercially-available integrated audio synthesizer instrument.

Moog is a legendary name in the world of music. As far as manufacturers/innovators of musical/audio equipment go, Robert Moog is a close to a household name as anyone I can think of. The original Moog Modular Synthesizer, as used in early ‘hit’ electronic records such as Carlos’ “Switched on Bach,” was the earliest commercially-available integrated audio synthesizer instrument.

But as much as Moog was indeed an innovator and a massive contributor to the world of music and audio, widespread acceptance of his (and others – Buchla, EMS, etc) synthesizer systems actually marked the demise of a much earlier tradition of electronic music practice. Because the Moog Modular, complex and inscrutable as it now seems, was in fact a massive simplification and streamlining of the earlier academic/institutional ad-hoc electronic music studio. Today we will start (what I intend to be) a series of investigations into the technology of early studios used by electronic pioneers such as Varese, Stockhausen, and Luening.

I am slowly-but-surely accumulating some of the original circa 1960 equipment similar to that which pre-Moog electronic music was created with, and I hope to attempt some of this early practice myself.

***********

*******

***

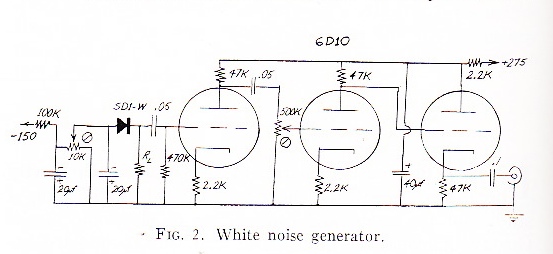

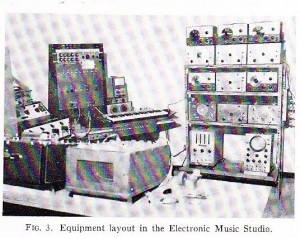

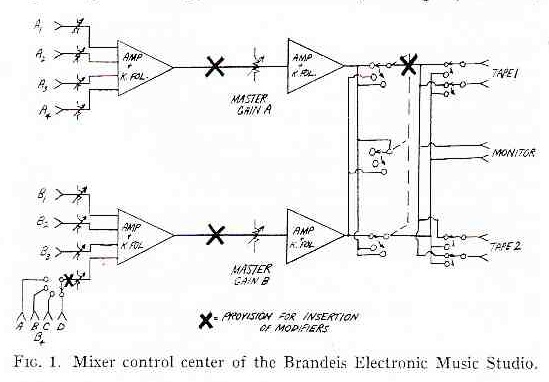

This article, from the same 1965 issue of the AES journal which heralded the arrival of ‘The Moog,” details a basic ad-hoc electronic studio of the era. Read through it. The basic components that Robert Moog integrated into his ‘modular instrument’ are all present in the Brandeis studio, minus the keyboard: oscillators, a mixer, a filter, a noise generator, a ring modulator, a spring reverb unit. And, of course, several tape-recorders to allow the various sounds to be layered and combined in order to meet the composer’s intent. In order to understand just how much effort was necessary to create even these basic conditions for composing, consider this: the (very simple) mixer had to be custom-designed and built by an engineering firm.

This article, from the same 1965 issue of the AES journal which heralded the arrival of ‘The Moog,” details a basic ad-hoc electronic studio of the era. Read through it. The basic components that Robert Moog integrated into his ‘modular instrument’ are all present in the Brandeis studio, minus the keyboard: oscillators, a mixer, a filter, a noise generator, a ring modulator, a spring reverb unit. And, of course, several tape-recorders to allow the various sounds to be layered and combined in order to meet the composer’s intent. In order to understand just how much effort was necessary to create even these basic conditions for composing, consider this: the (very simple) mixer had to be custom-designed and built by an engineering firm.

And the studio-staff themselves designed and built the white-noise generator that the set-up used.

And the studio-staff themselves designed and built the white-noise generator that the set-up used.

*******

***

Columbia University had a similar, but much more sophisticated studio at the time. They began the construction of their set-up in 1952, nine years before Brandeis did the same.

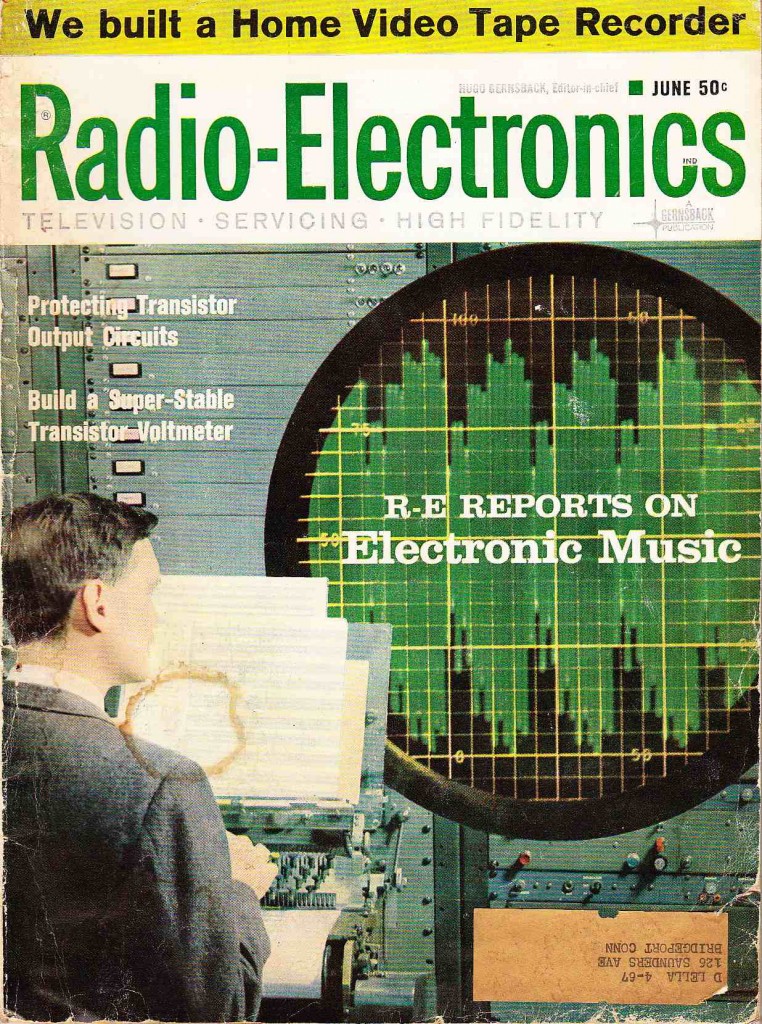

Here the Columbia/Princeton studio is profiled in the June 1965 issue of ‘Radio Electronics,’ the same year that the AES covered Brandeis.

You can here some of the music that Otto Luening made on this rig (presumably) at the youtube link earlier in my article. I find it to be very beautiful; it is in many ways the most basic type of music: I think we experience it directly as ‘Organized Noise,’ as free-as-possible from cliche and expectation. Just my $.02.

You can here some of the music that Otto Luening made on this rig (presumably) at the youtube link earlier in my article. I find it to be very beautiful; it is in many ways the most basic type of music: I think we experience it directly as ‘Organized Noise,’ as free-as-possible from cliche and expectation. Just my $.02.

***********

*******

***

As I had mentioned earlier, Moog’s real innovation was to take all of the disparate components of electronic sound-generation – the oscillators, mixer, filters, noise generator, ring modulator, a spring reverb – and combine them into little panels that fit a single chassis, with a conventional piano-type keyboard as the primary input-control device.

But where did our pre-Moog pioneers source their hardware? As the c. 1965 coverage indicates, Brandeis and Columbia had some of it custom built; some was built by the staff; and some originated as non-musical laboratory equipment.

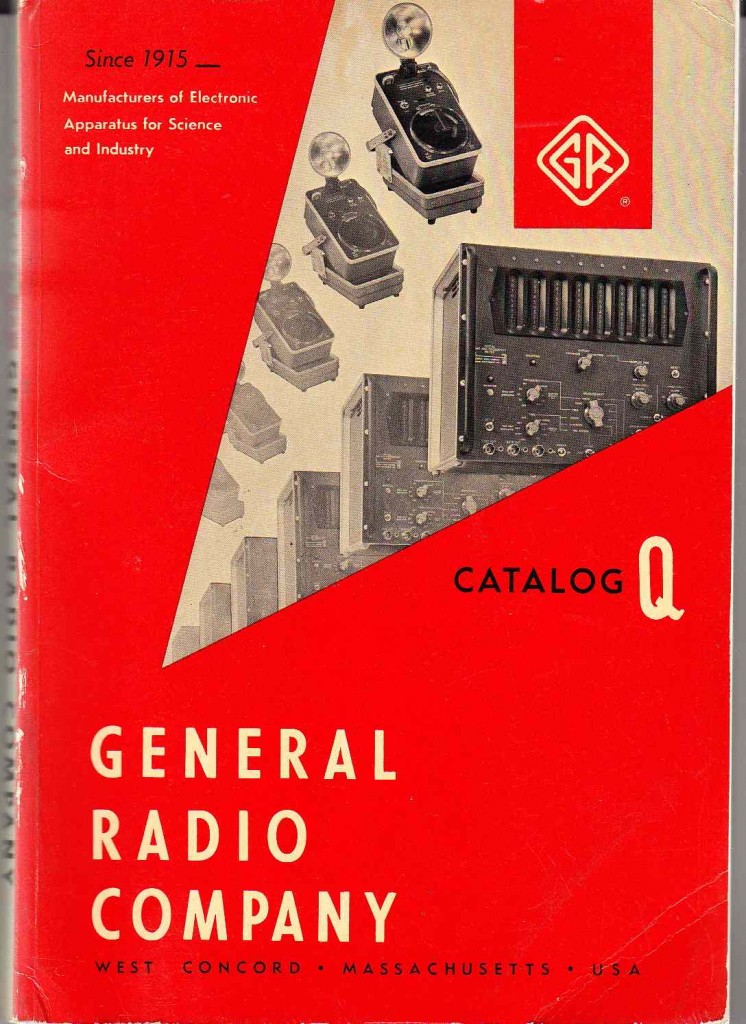

General Radio was perhaps the pre-eminent manufacturer of electronic test equipment in the 1950s and 1960s. I have owned some of their pieces, and the build-quality is absolutely incredible.

General Radio was perhaps the pre-eminent manufacturer of electronic test equipment in the 1950s and 1960s. I have owned some of their pieces, and the build-quality is absolutely incredible.

This type of hardware is fairly easily obtained nowadways for very little money – i generally pay $5 – $20 for a unit – and usually it still works. Sometimes it is hard to resist the temptation to chop up these pieces in order to use the valuable transformers for other projects, but I have saved a few of the better pieces in the hopes of getting my own super-primitive Electronic Composing Studio together.

*******

***

Anyone out there ever made music on a pre-Moog system?

Anyone attend the Brandeis or Columbia programs in the early 1960’s? Drop a line and let know about it.