A few years ago I bought a pile of old electronic parts from an anonymous junk dealer. Random stuff- 5 lbs of crappy ¼” jacks, some VU meters, a box of giant knobs, etc. The dealer also had a box of old AES Journals.

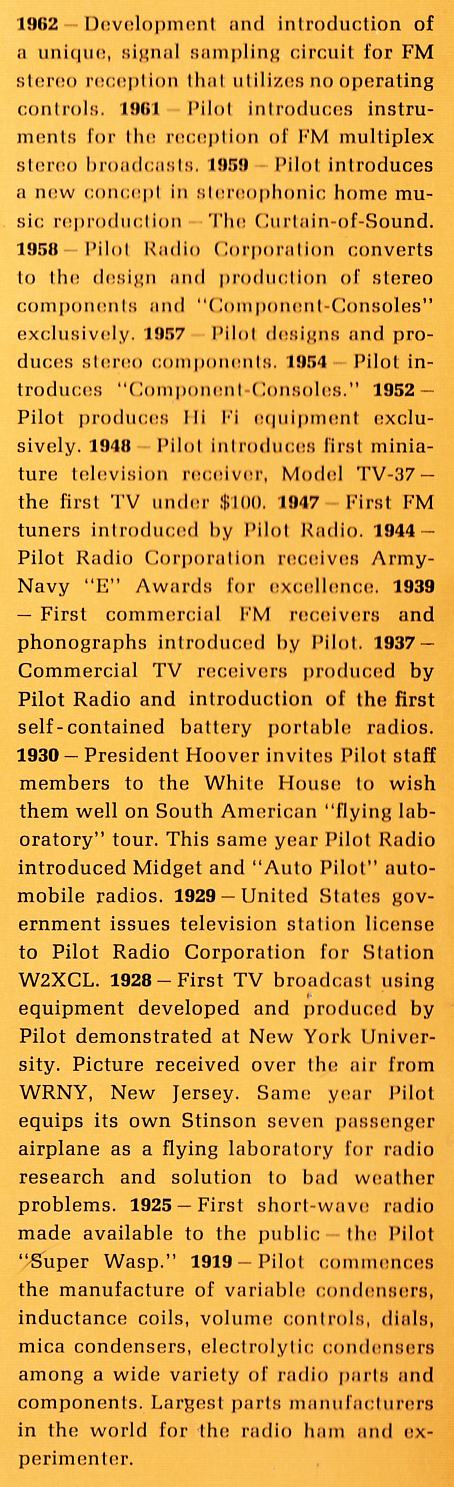

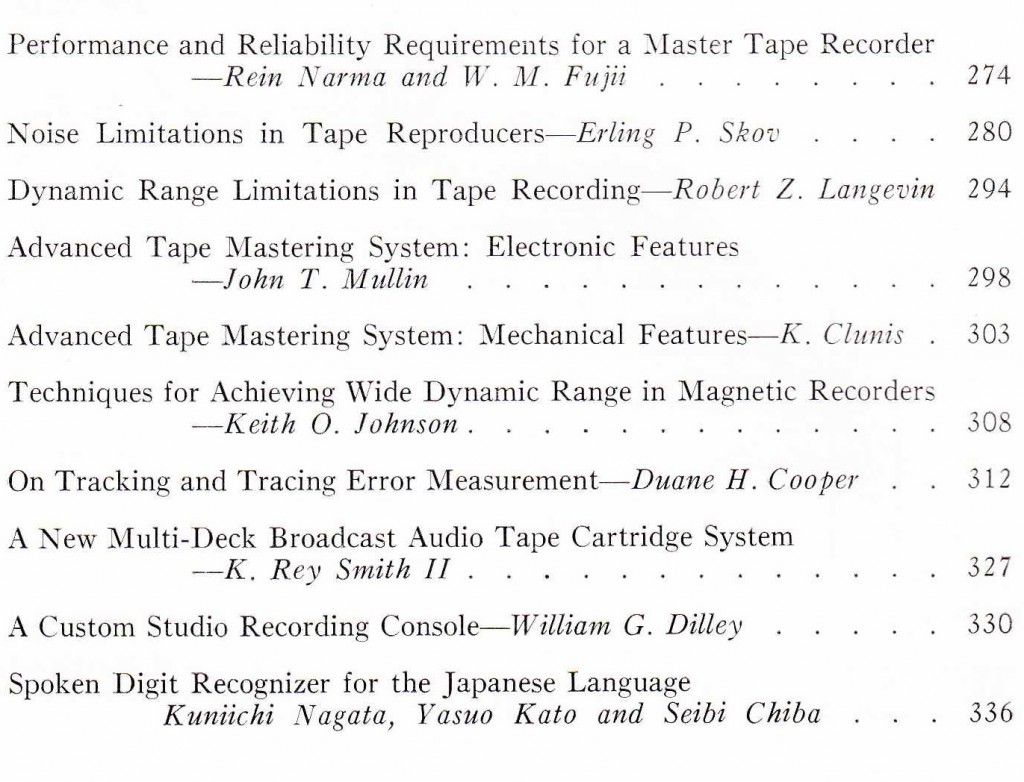

The AES, or Audio Engineering Society, is just what the name suggests. A professional organization for those who work in audio. I don’t know what the main focus of the AES is nowadays (i am not a member), but in the early 1960s it was very technical. Not so much an organization for people who engineer audio (IE., use equipment to manipulate audio signals), but rather an organization for people who engineer the equipment that recording engineers would then use to manipulate audio. Let’s put it this way: there’s a lot of math involved. Here’s a contents page from 1964. This issue was devoted to tape-recorder noise reduction. As in, designing the circuits. Not just building or using them.

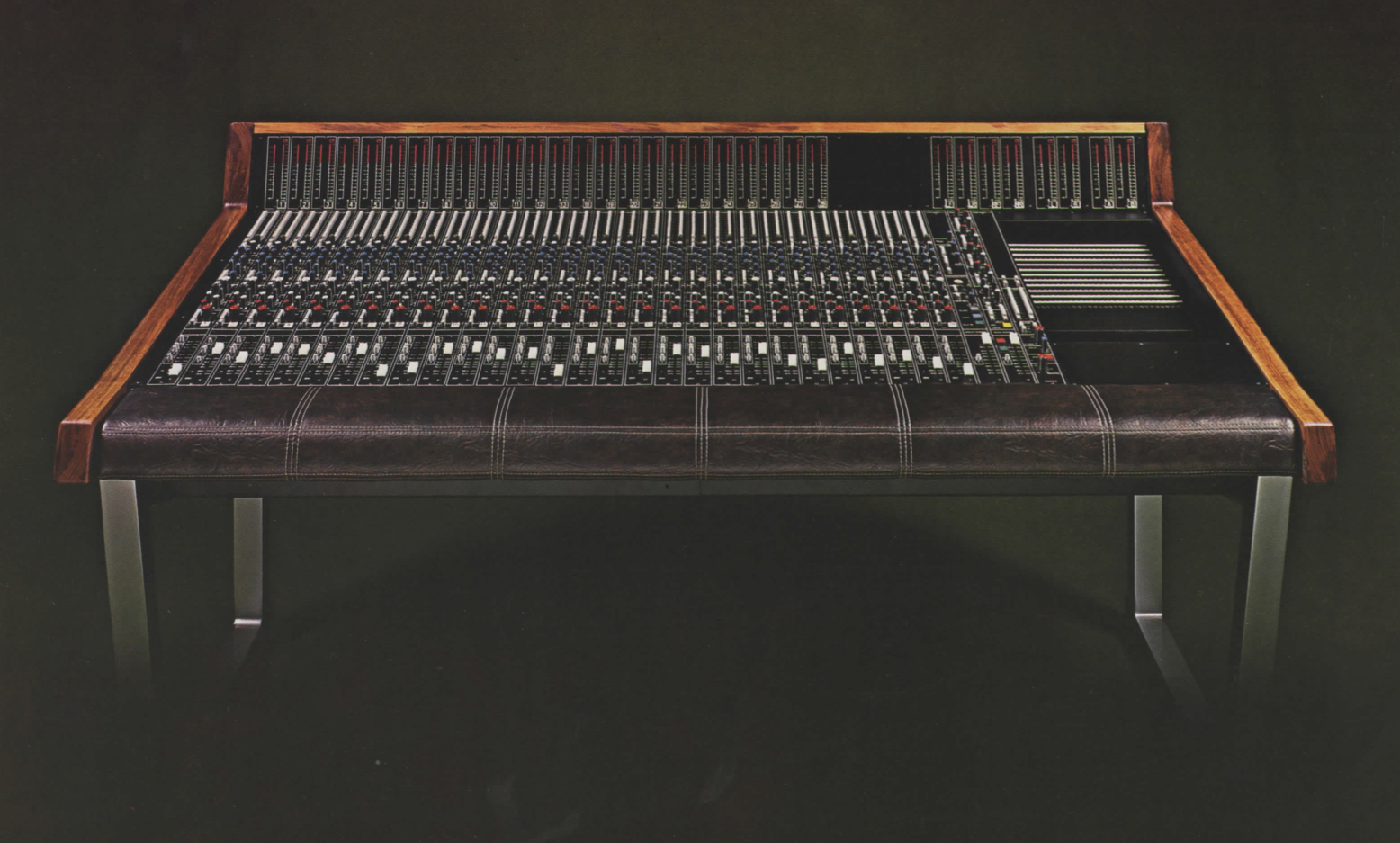

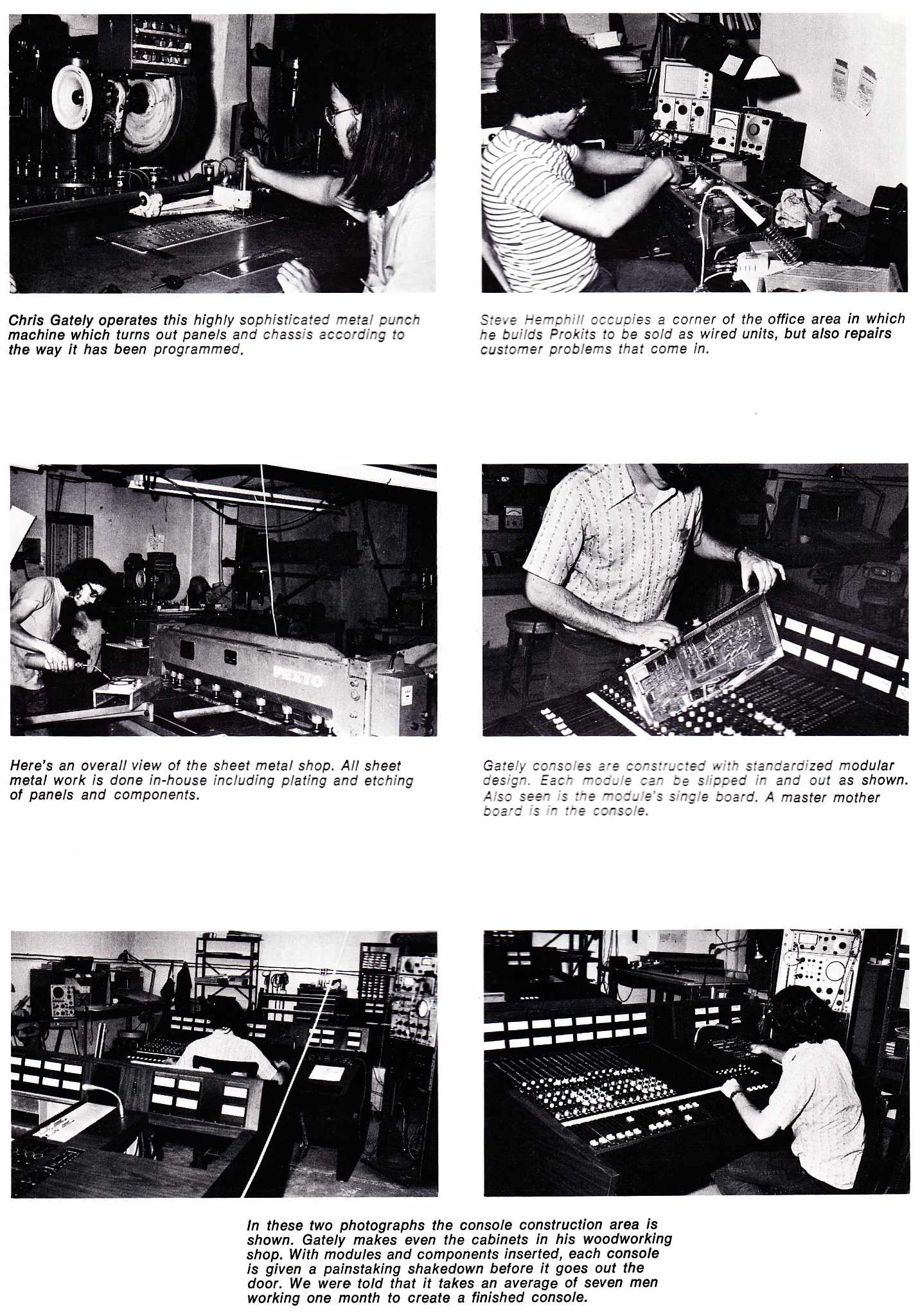

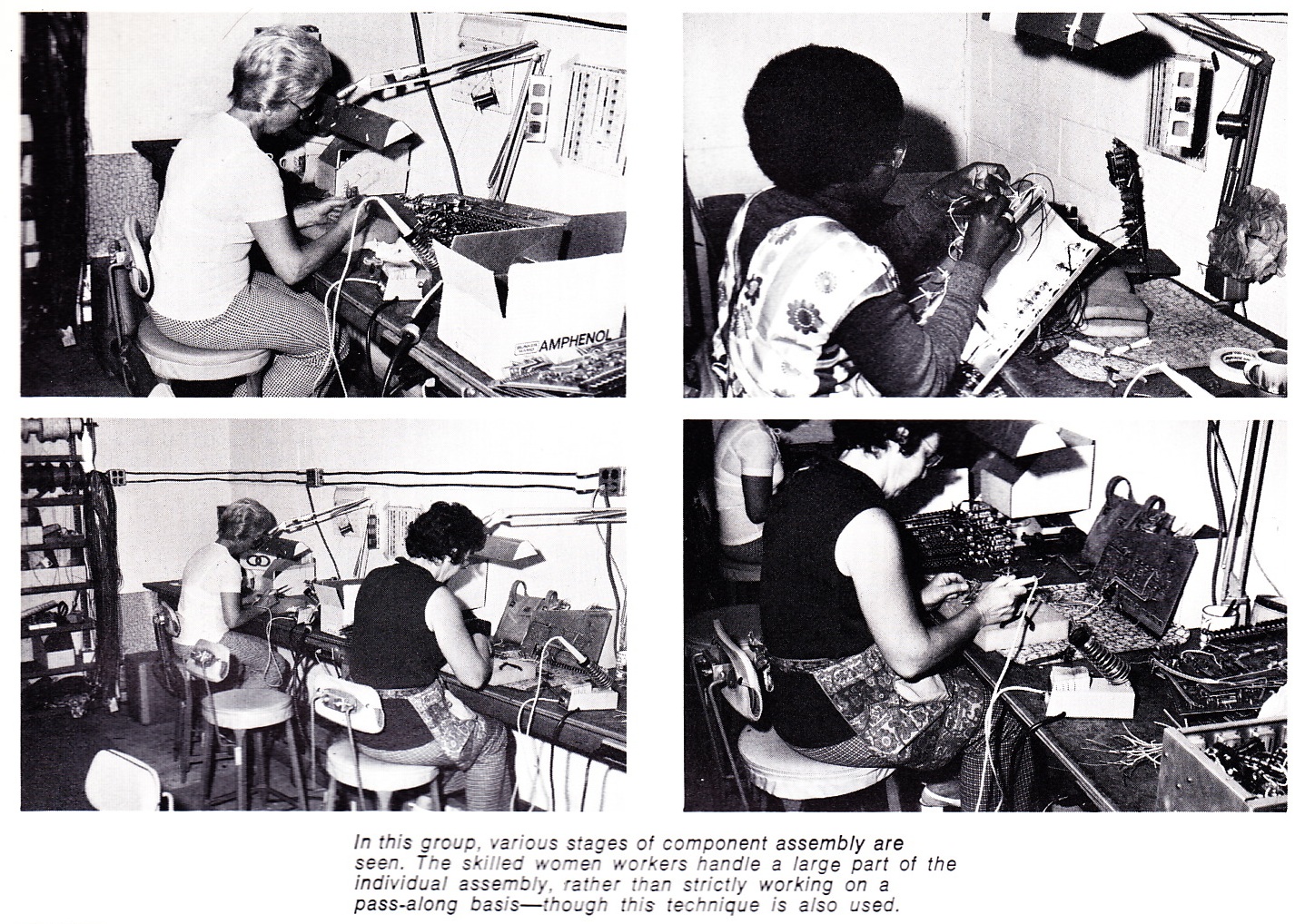

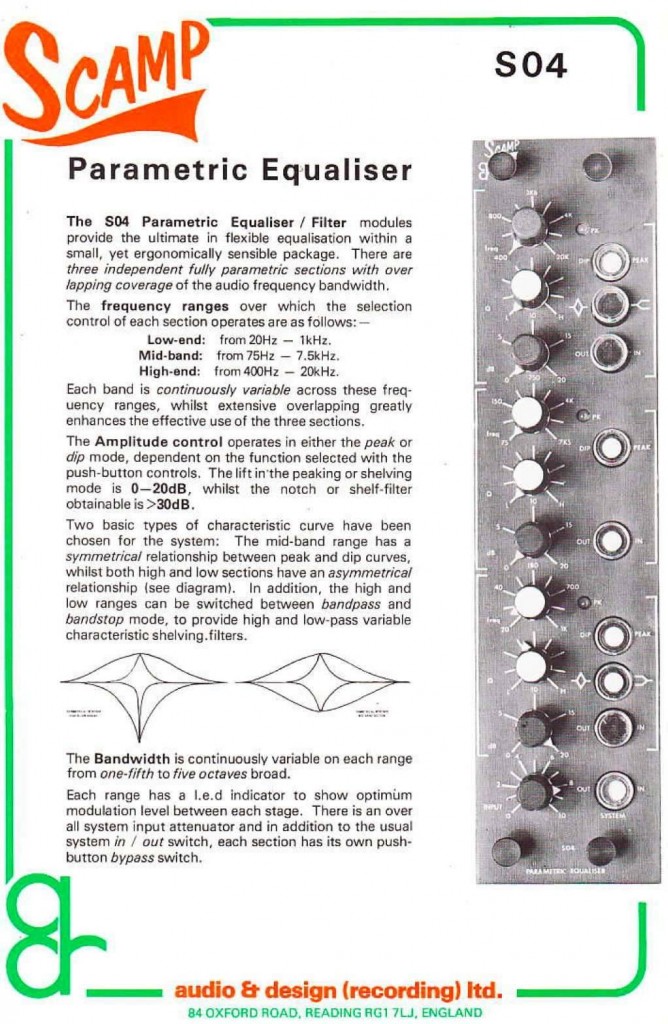

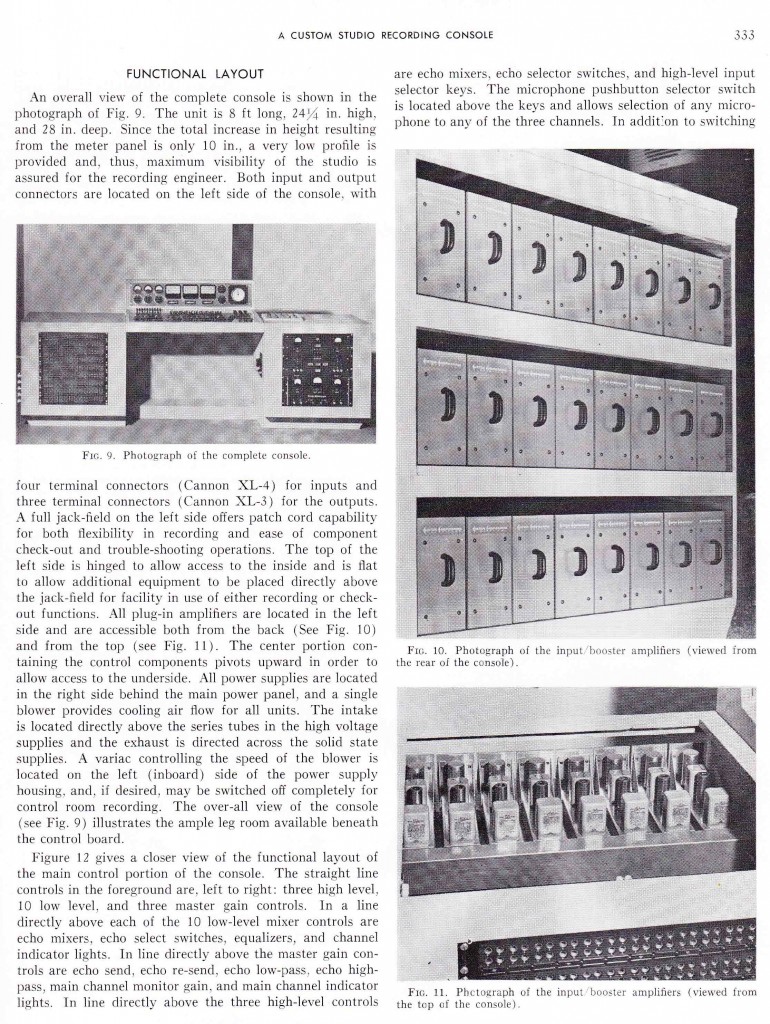

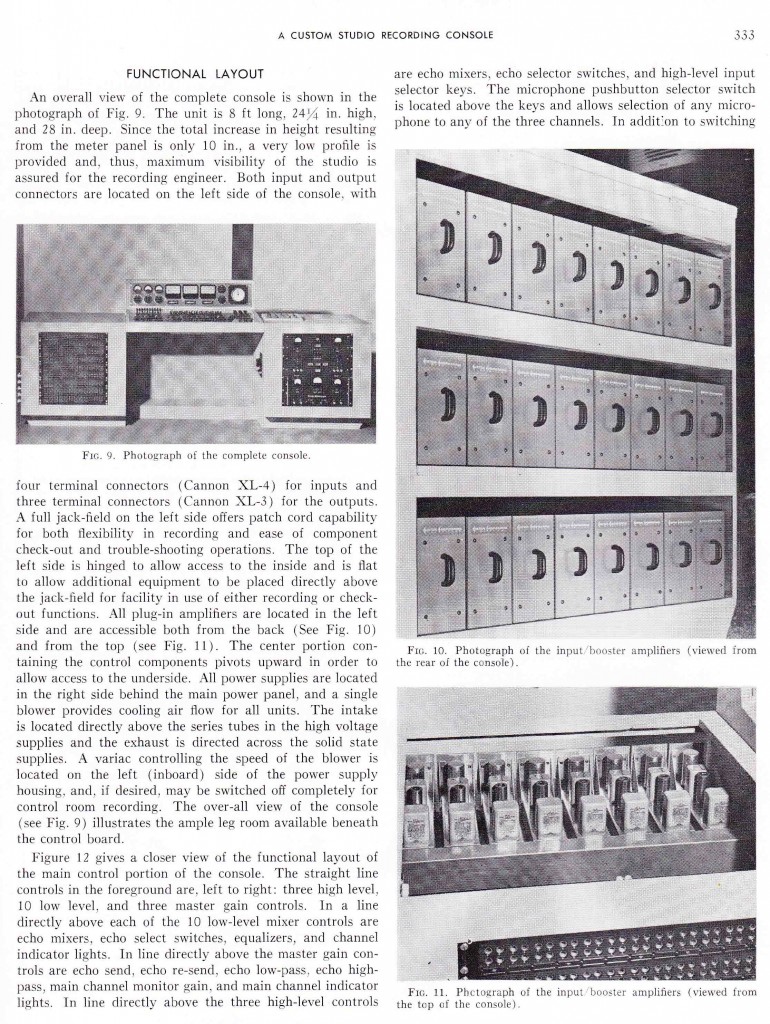

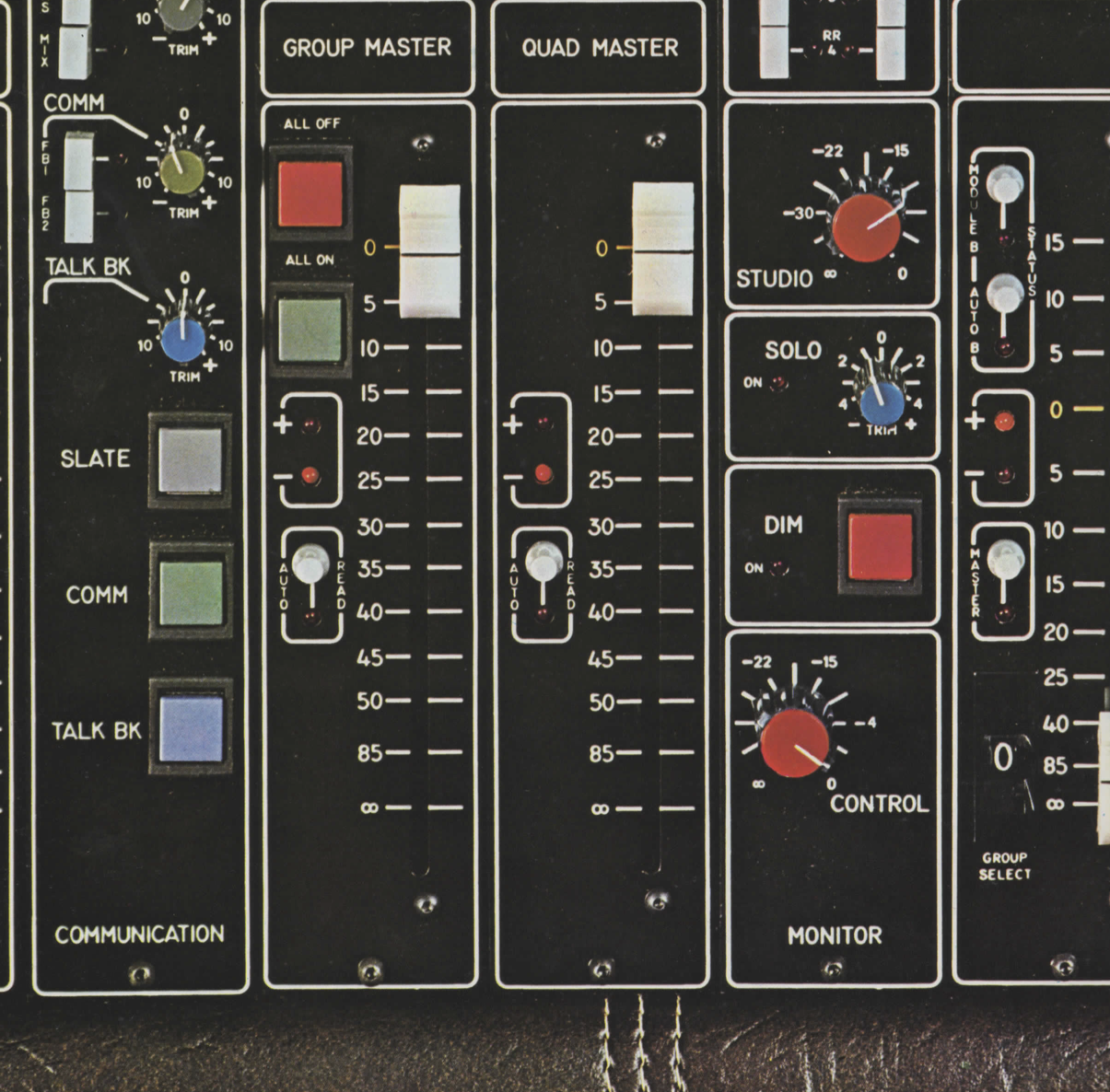

There are some more accessible articles, like this piece detailing a custom-made audio console:

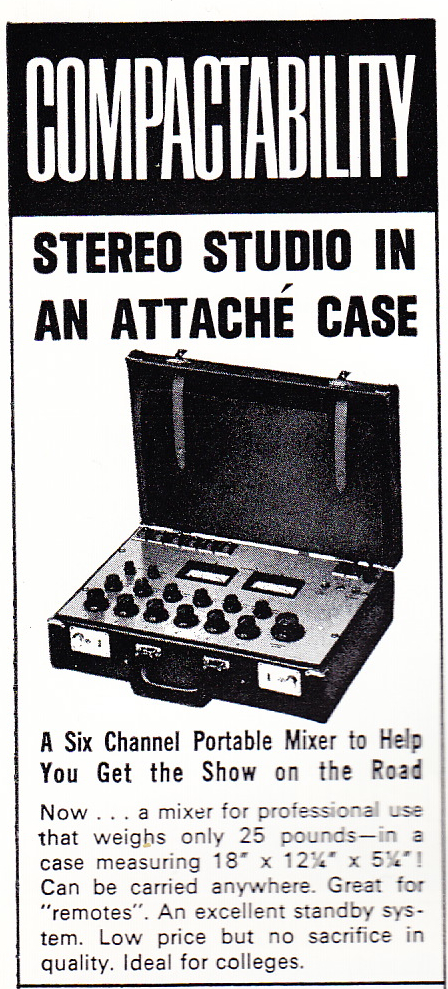

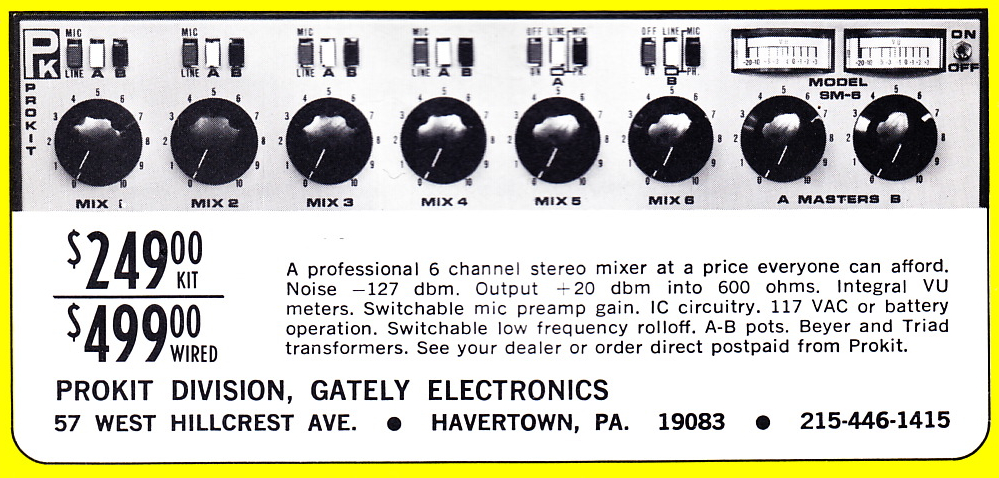

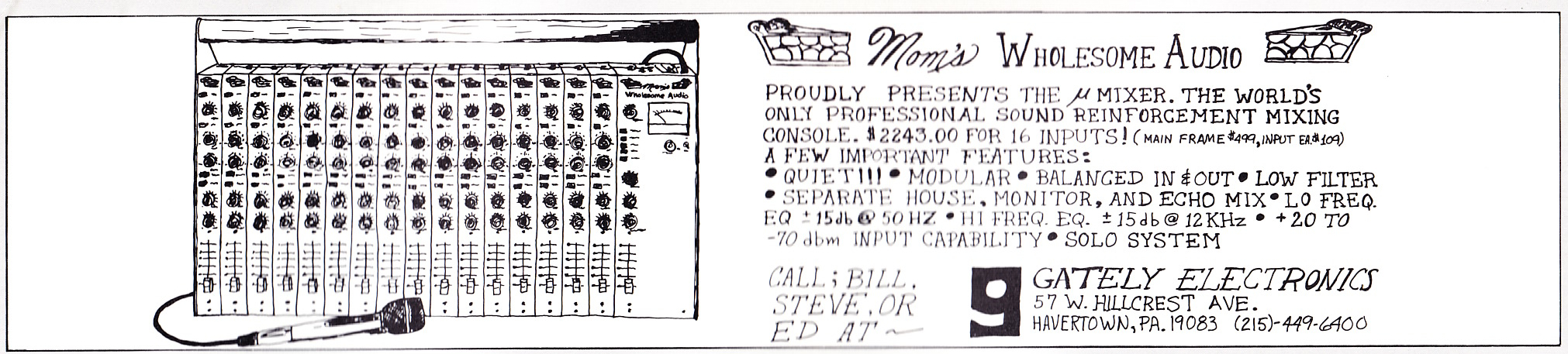

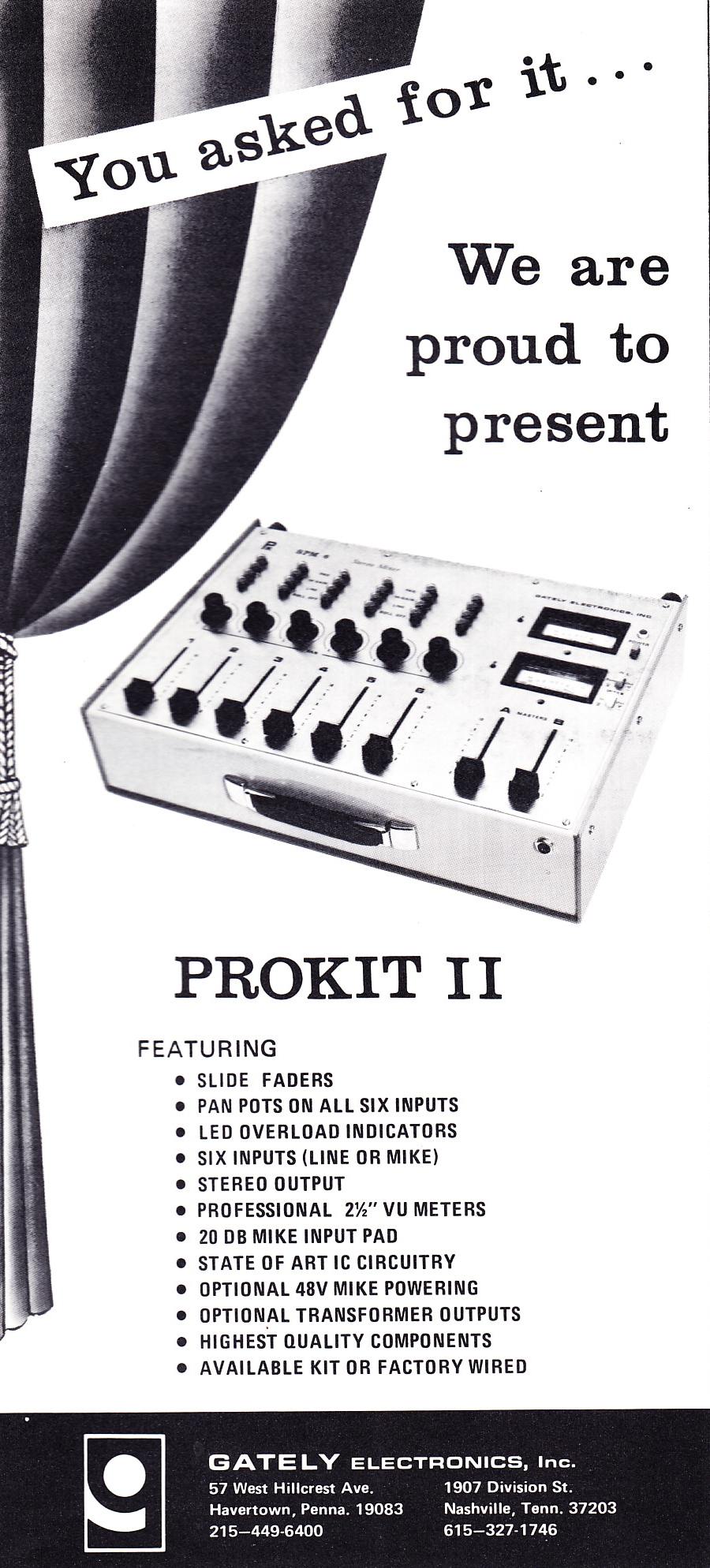

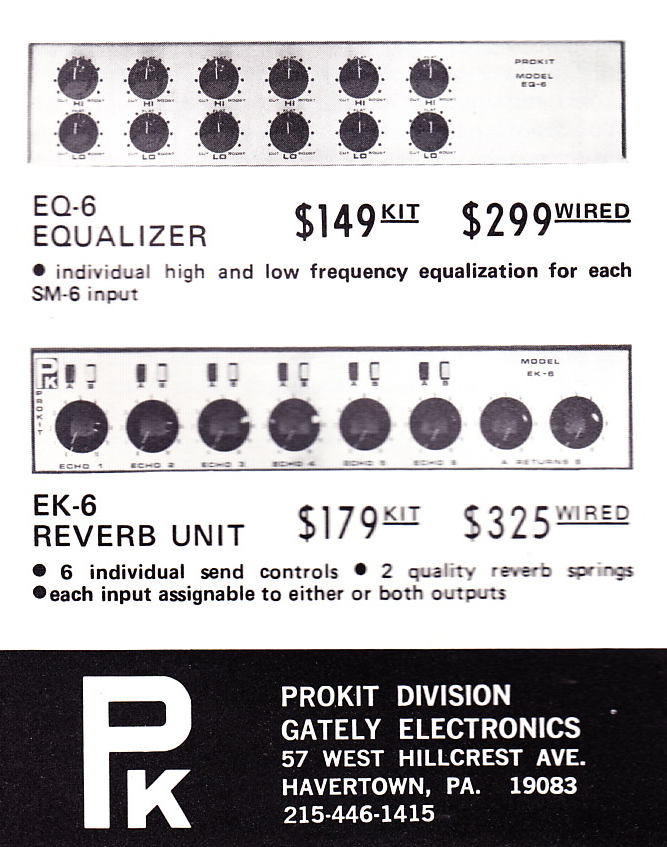

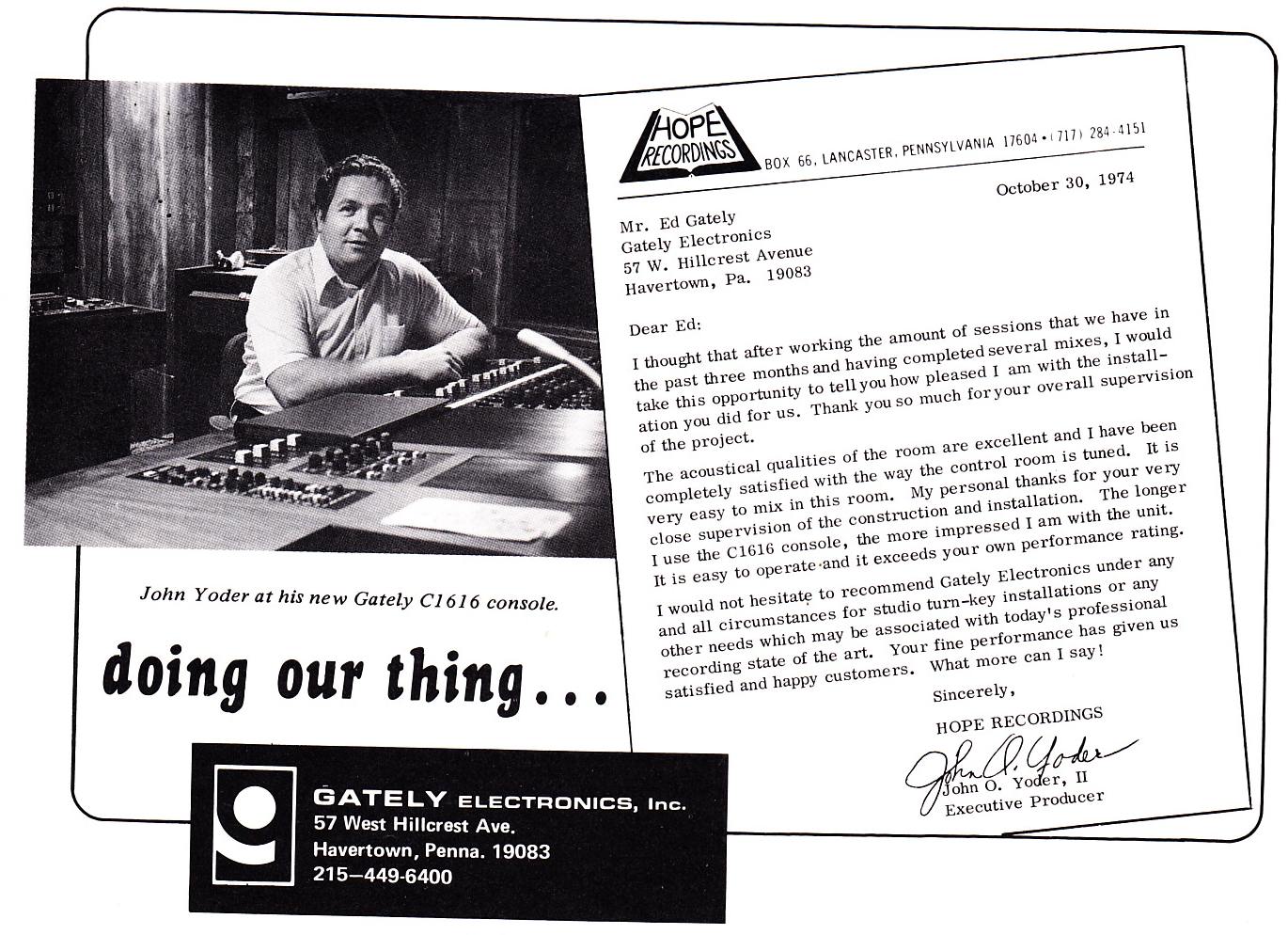

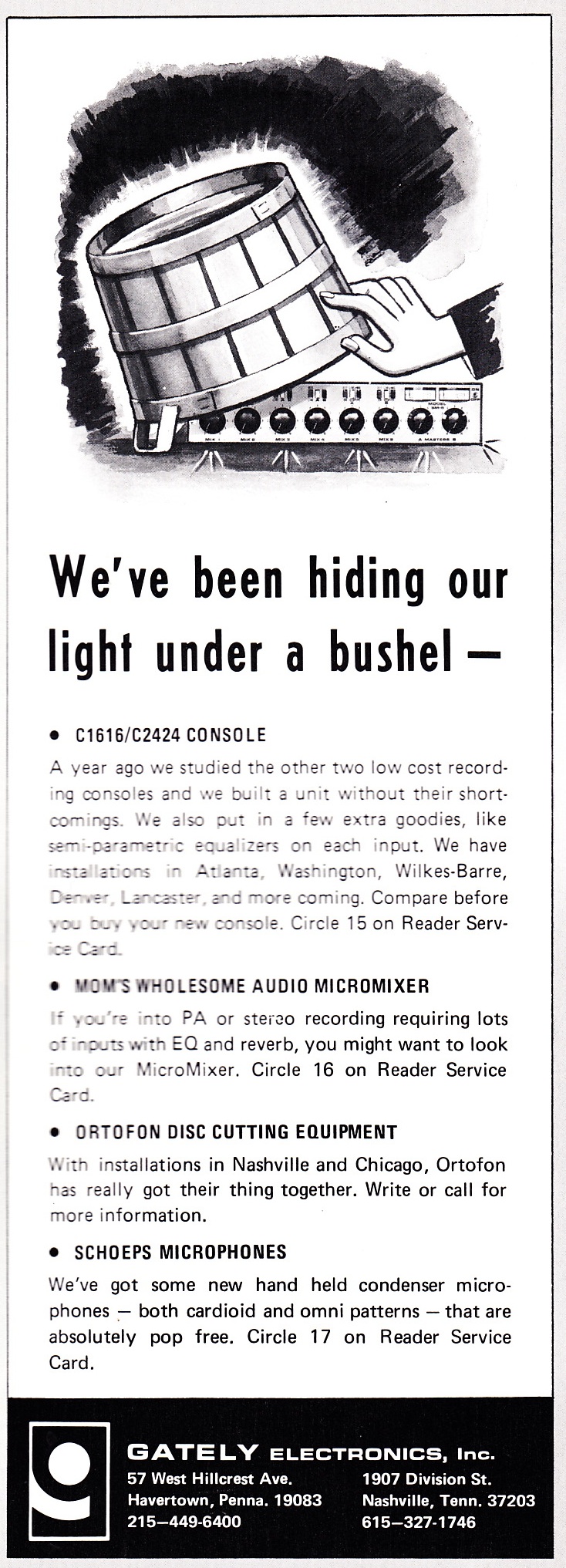

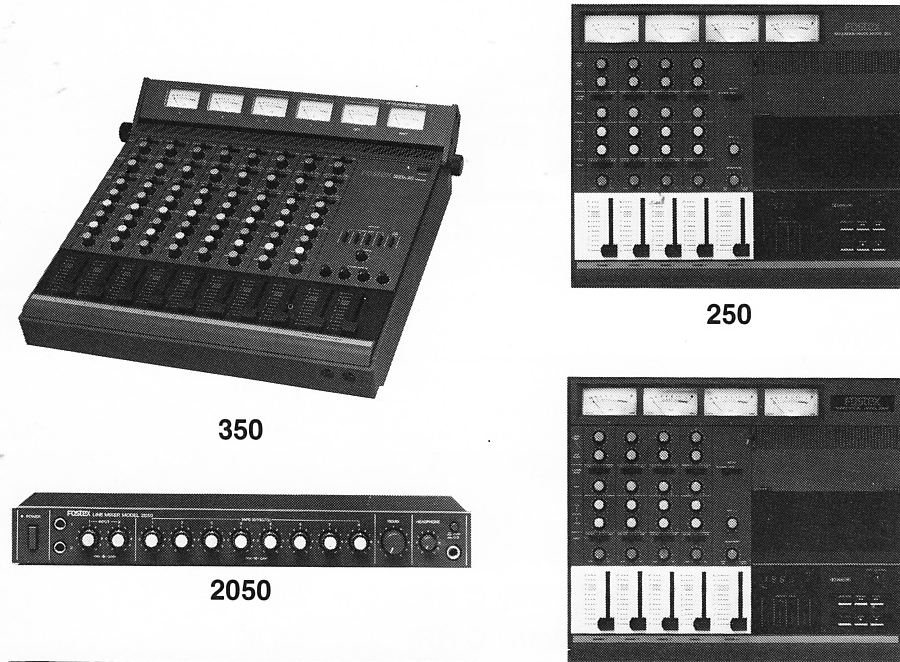

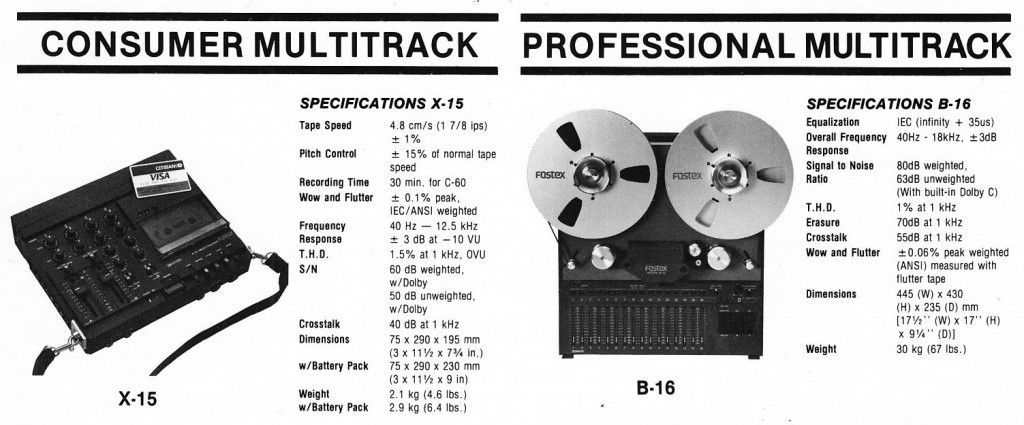

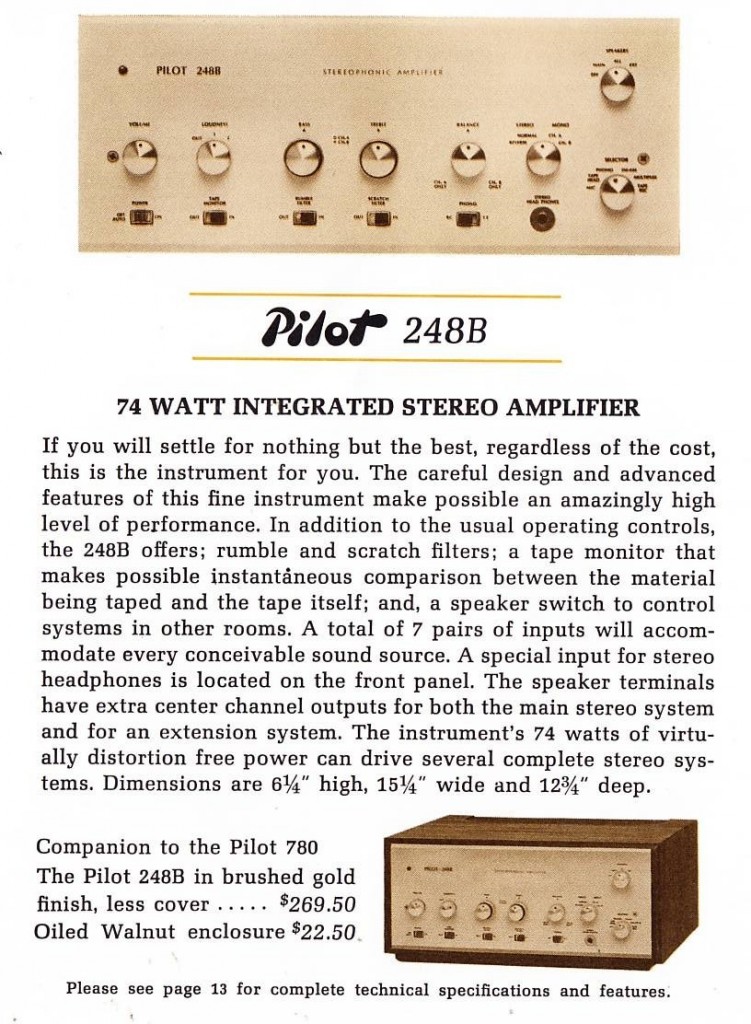

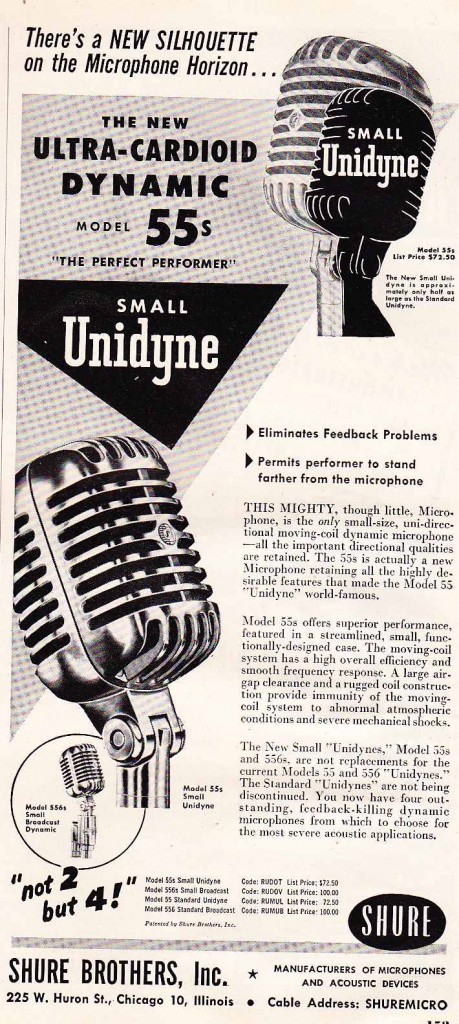

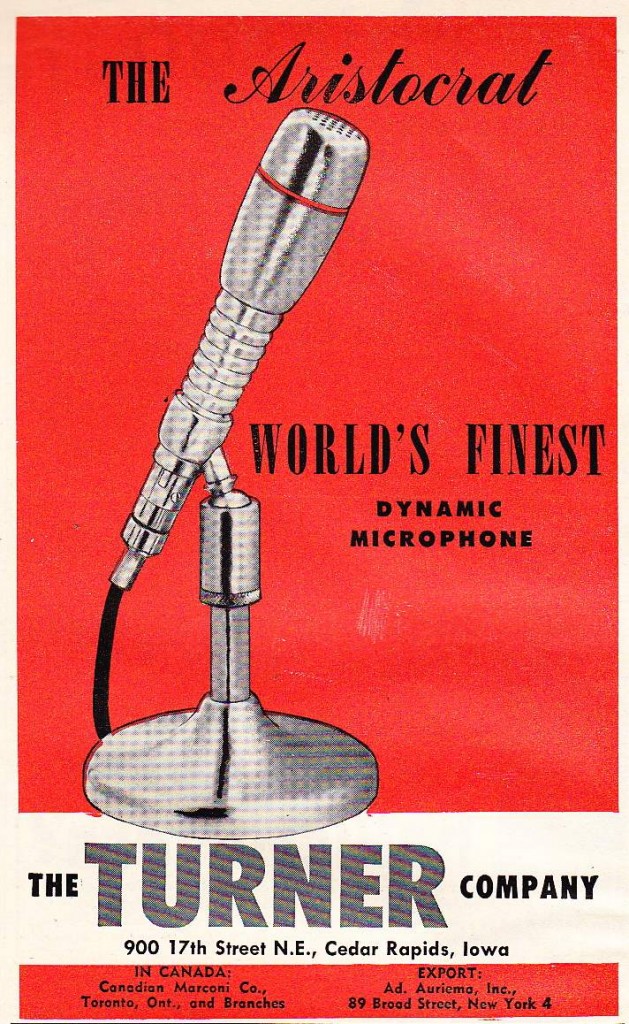

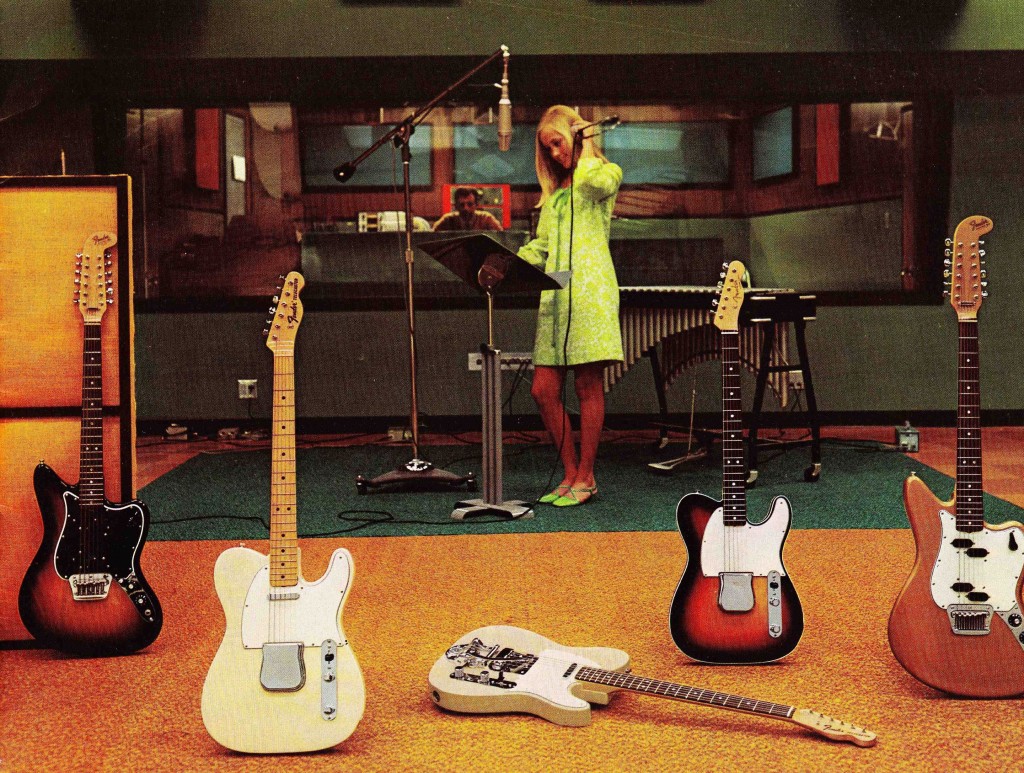

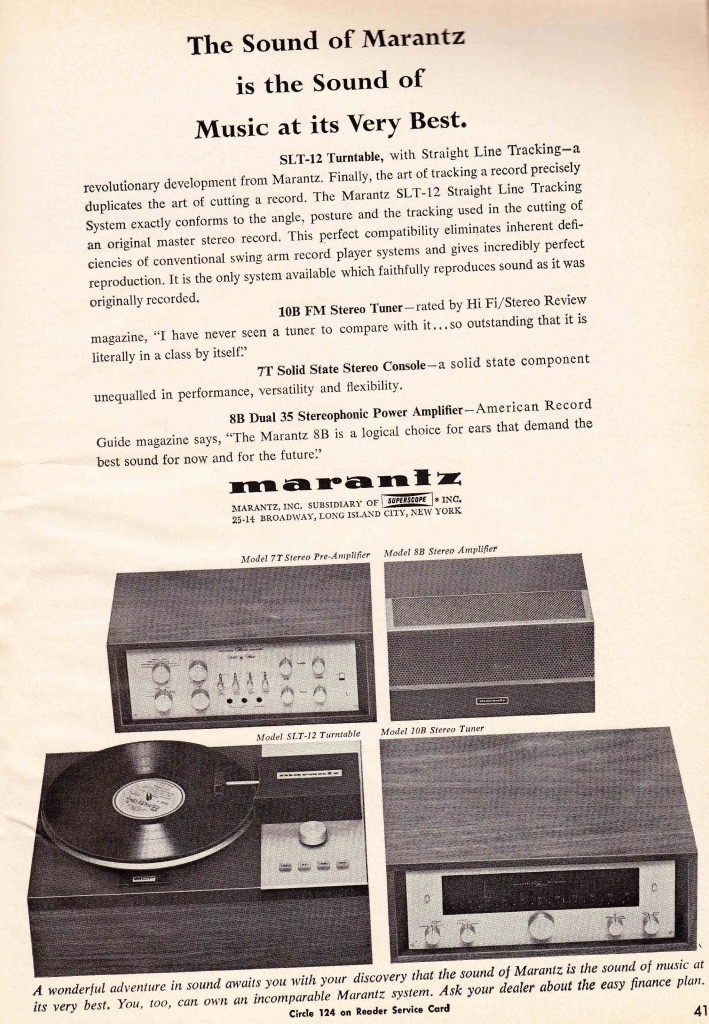

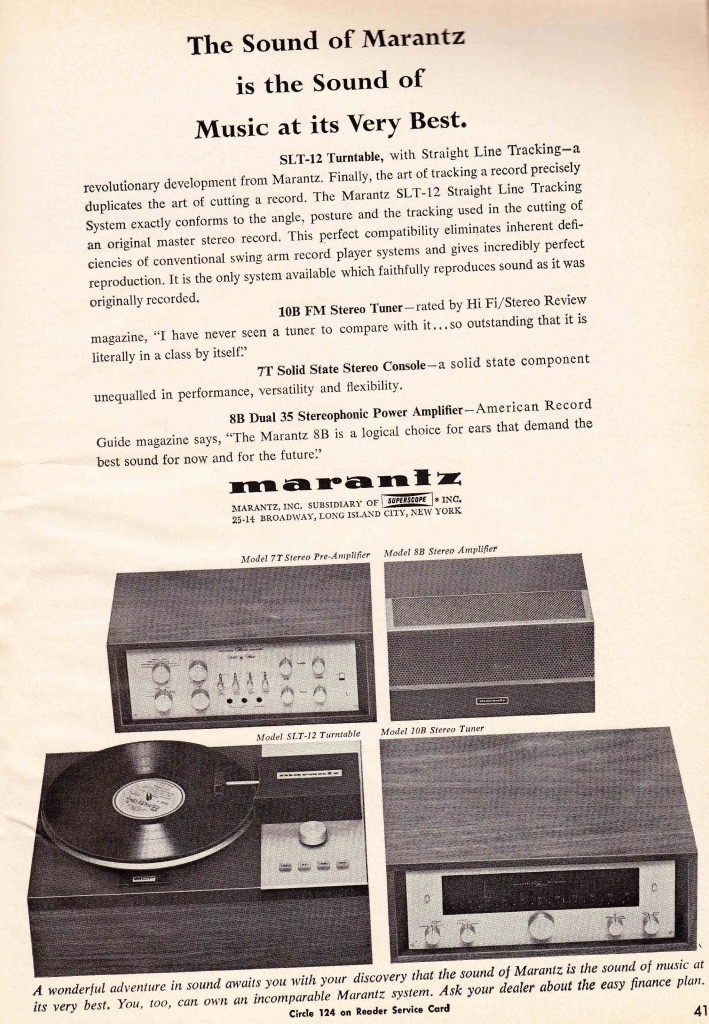

…and, of course, all those great old advertisements.

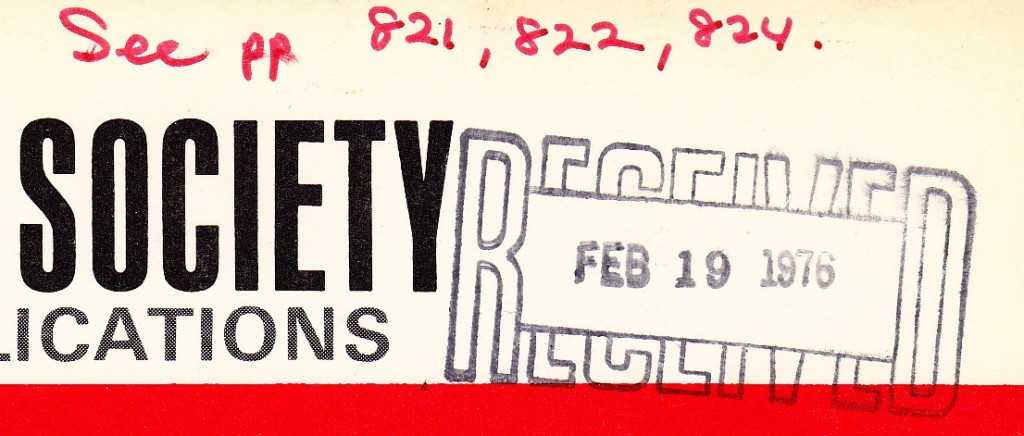

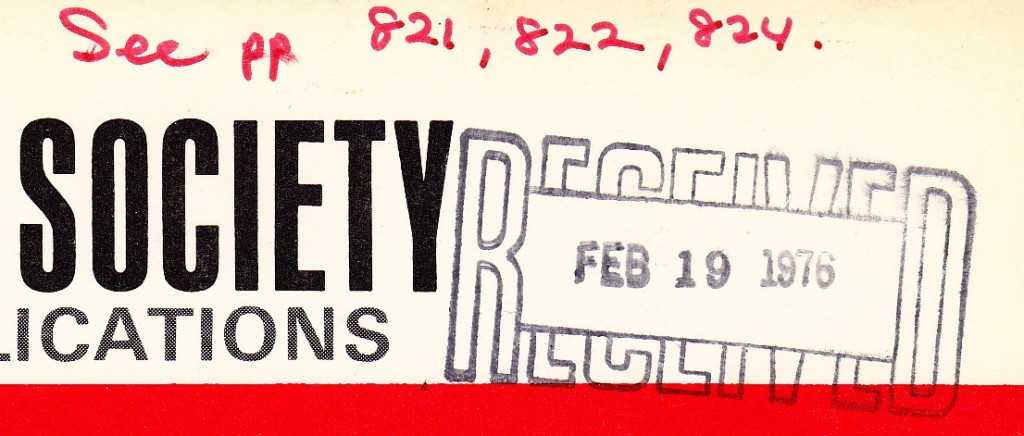

Anyhow, when i had the chance to examine the circa-1970 AES journals that the dealer sold me, it became apparent that they had once been the property of one Saul Marantz.

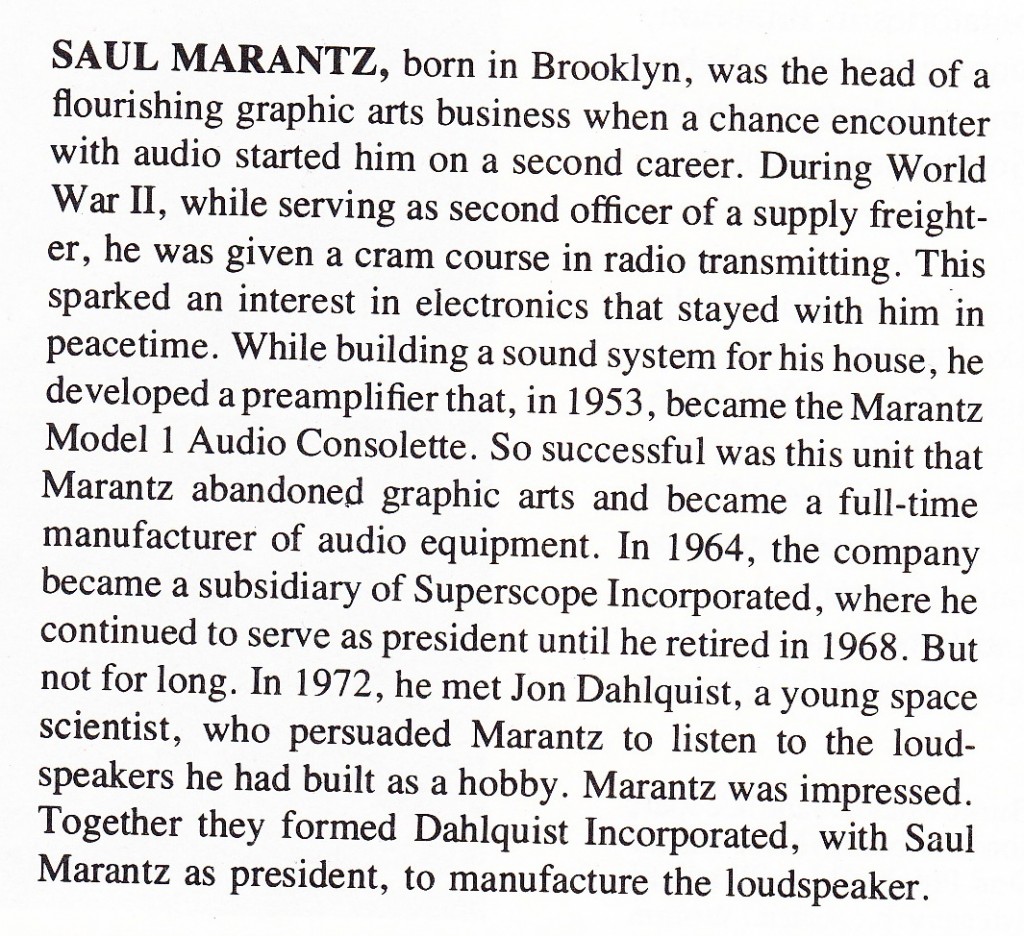

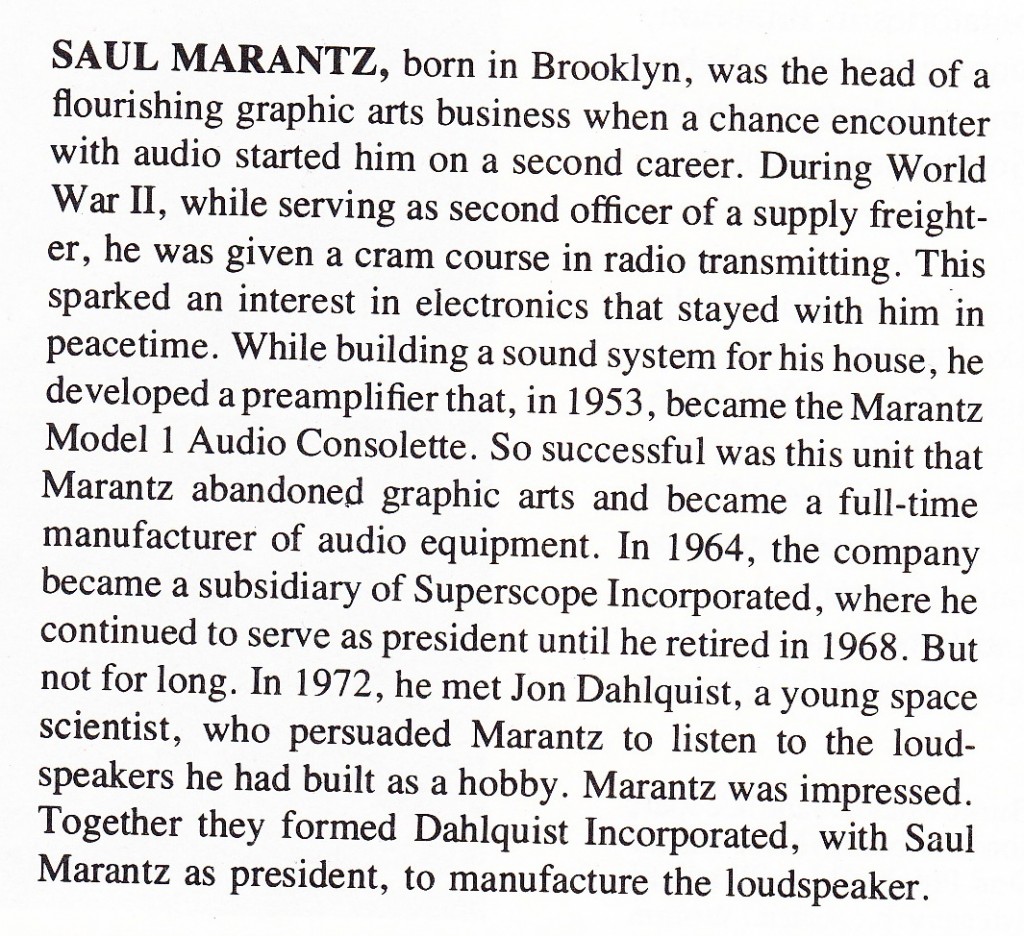

I knew the name Marantz as it applies to audio equipment – my wife in fact has a complete (circa 1995) Marantz hi-fi system in her studio – but i knew a little about the man. Turns out he was a fascinating character.

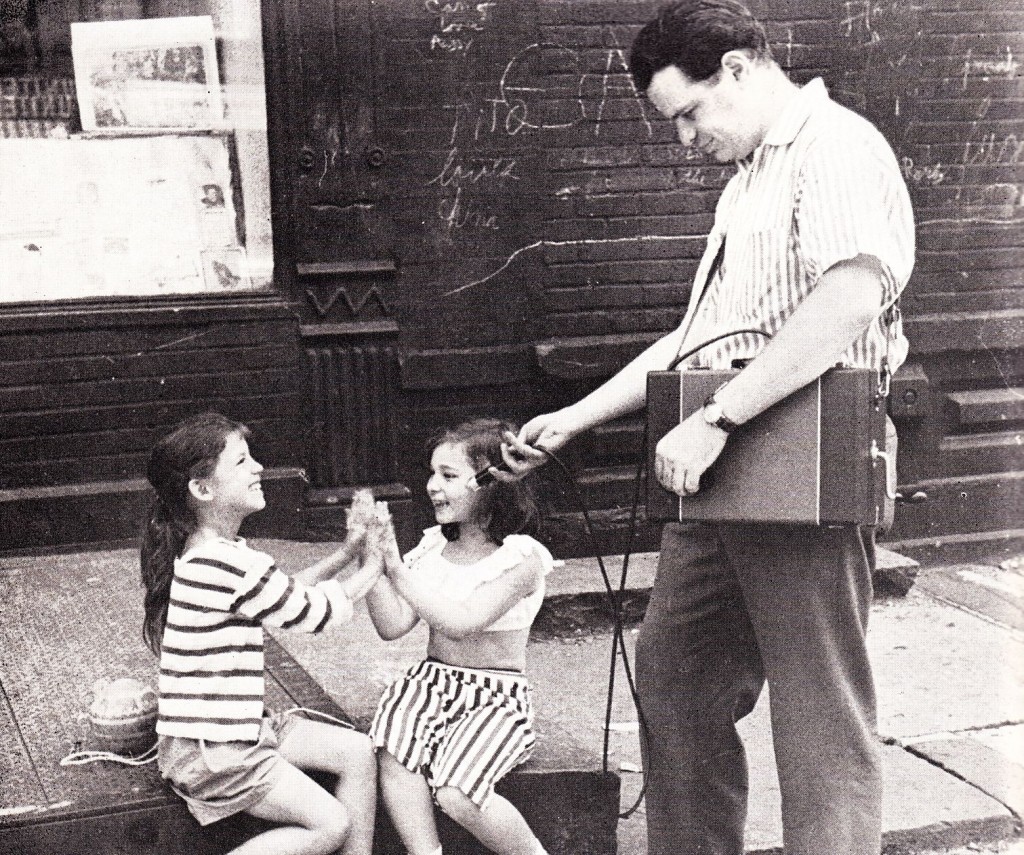

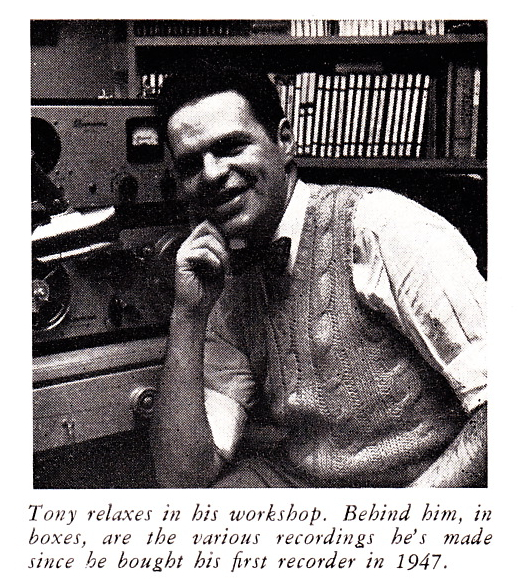

From the NYtimes: “ A man of many parts — photographer, classical guitarist, graphics designer, collector of Chinese and Japanese art — Mr. Marantz was fascinated by electronics from his boyhood days in Brooklyn. His passion for music led to his first attempts at building audio components…. After service in the Army during World War II, Mr. Marantz and his wife, Jean Dickey Marantz, settled in Kew Gardens, Queens. One day in 1945, he decided to rip the radio out of his 1940 Mercury, where he rarely listened to it, and put it to more practical use in his house. But that transplant required building additional electronics to make the radio work indoors. Such was the hook that snared Mr. Marantz for life.”

Saul Marantz was a career graphic designer at the time. He left this career once his Hi -Fi components (co-designed with engineer Sidney Smith) took off.

Learning that S. Marantz had been a graphic designer (and collector of Japanese art) really put the puzzle together for me. The extremely elegant appearance of all the Marantz products (until he left the company in 1968, at least) always made a big impression on me. Early Marantz hardware was high-end, sure – with prices and specs close to McIntosh pieces – but their visual design is in a league buy itself.

(web source)

(web source)

In another of the Marantz AES journals, S. Marantz receives an achievement award for outstanding contribution to consumer audio equipment.

The ‘classic’ Marantz designs were introduced between 1950 and 1964. After that point, it became a ‘name-only’ company. The more recent Marantz-branded products are of good quality, for what’s it worth.

How important are visuals to your appreciation of audio hardware? How important the tactile interface with the devices?

When everything is reduced (enhanced??) to a touch screen, with the visual experience of audio tools be heightened, or reduced?

we’re probably in the same karass

we’re probably in the same karass and if you get that second reference as well

and if you get that second reference as well