I had often heard of primitive ‘field-coil’ speakers, but it was not until i was confronted with a pair of them that I actually had to come to grips with this ancient technology.

Consider how a basic modern speaker driver works. See this excellent animation for a quick example.

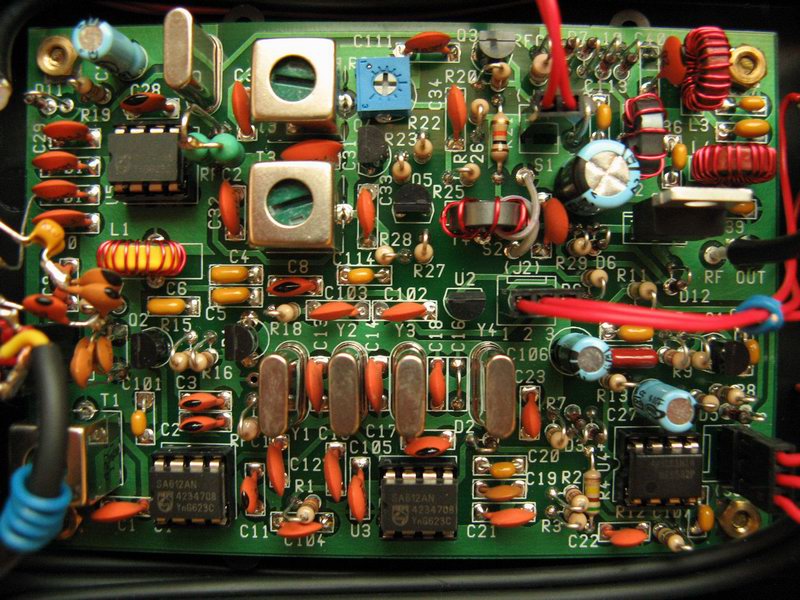

There is a (usually) paper cone with some wire wrapped around a center post. The wire coil sits roughly inside a ring of magnetic material (either ceramic or metallic).

An electrical-signal is sent into the wire coil, and this causes it move relative to the fixed magnet.

OK so we all know what a paper cone is. And we all know what a coil of wire is. But what about this magnet? Where did it come from?

Well, it turns out that modern speakers use what are called ‘permanent magnets.’ As-in, the magnet has a permanent charge. The material which composes the magnet is always magnetic, regardless of any other influence. Hold a key up to the back of any raw speaker driver and you will see that yes this is in fact a magnet. And a pretty powerful one.

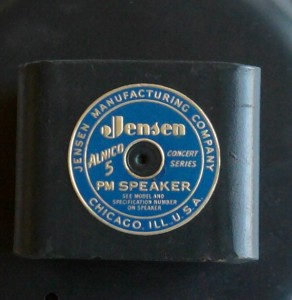

Permament magnets possesing enough magnetic power to function in a speaker driver are not naturally occurring materials, though. They had to be invented. And they were, largely as part of American WW2 engineering efforts. These new, powerful permanent magnets were engineerd from an alloy of aluminum, nickel, and cobalt, hence their name: Alnico magnets. In the 1950s, newer ‘ceramic’ permanent magnets were engineered, and these became the norm owing to their even greater efficiency and lower cost (cobalt is expensive as a raw material).

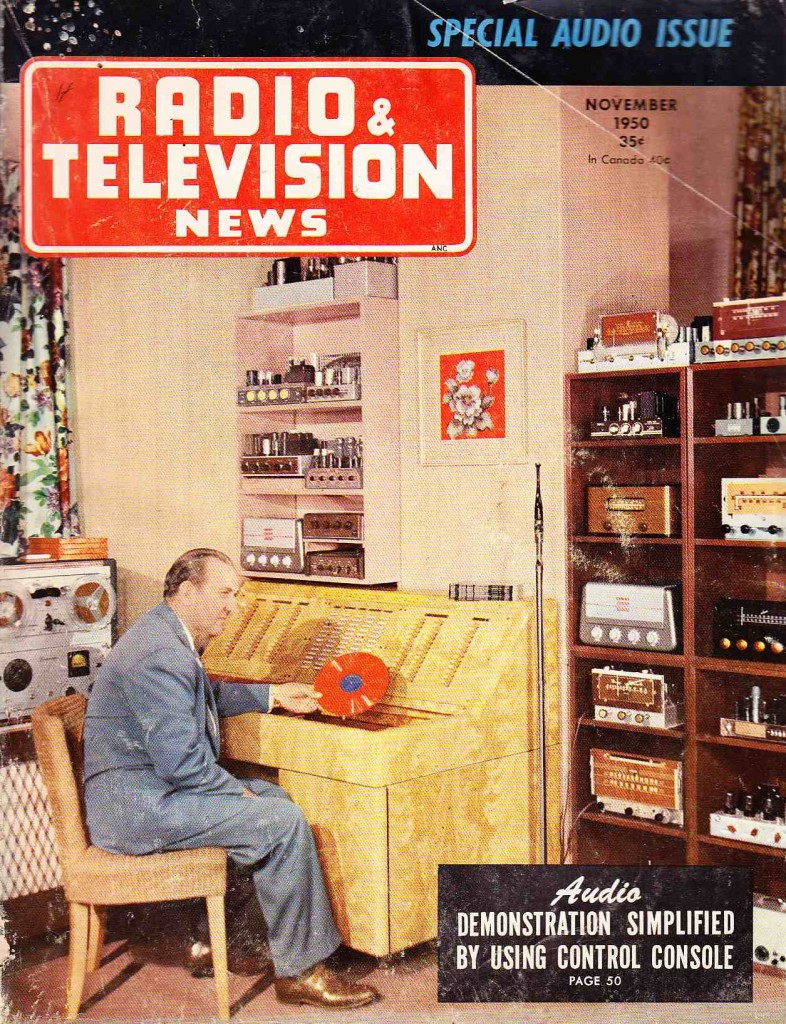

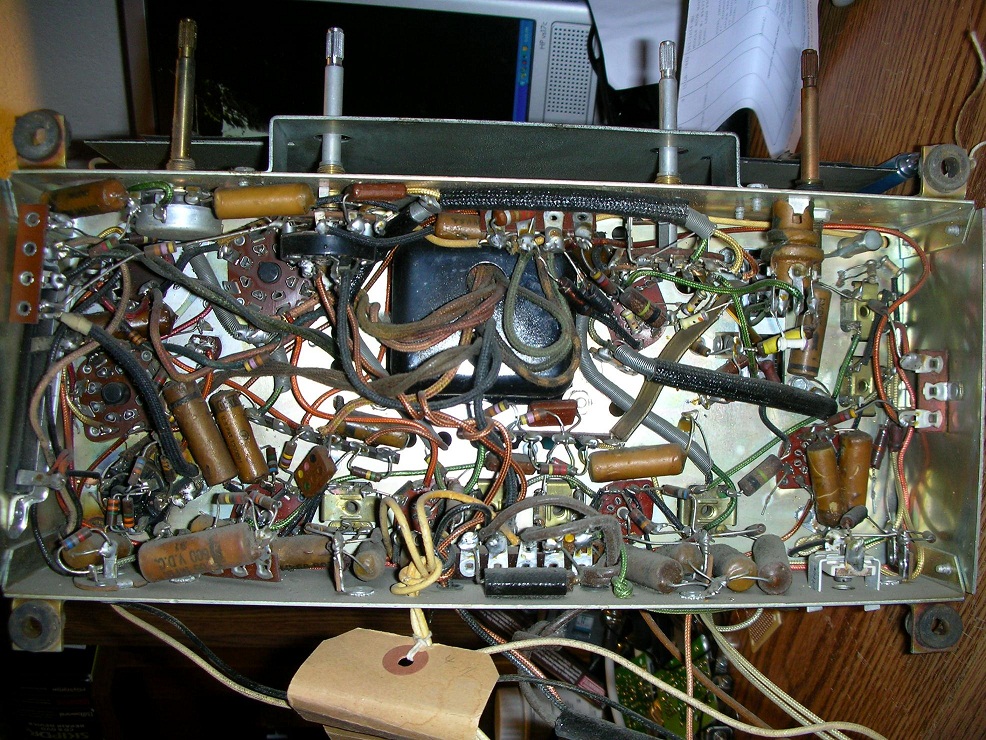

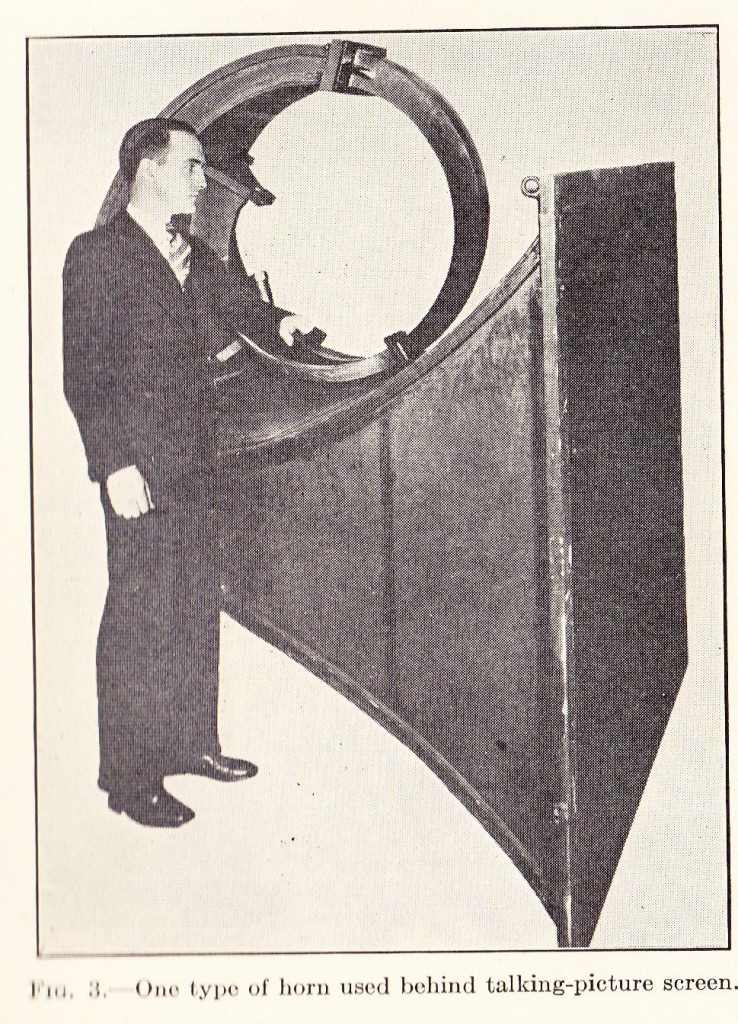

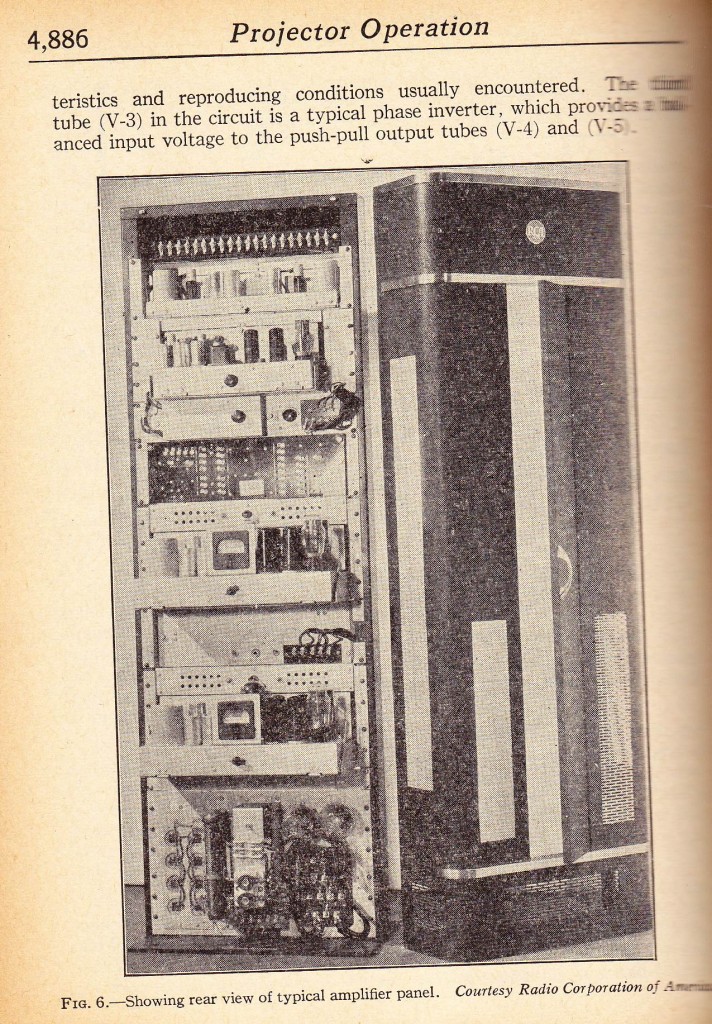

But what about all the speakers and guitar amps designed BEFORE the invention of this wonderful Alnico substance? These devices (and it’s rare to find one that is still in good working condition) use similar looking speakers, but with a very different type of magnet. They use Electromagnets. Meaning: they use magnets which are made of a material which only become magnetic when a large DC current is passing through it.

Exactly where the audio device creates this large DC current, and exactly what effect this arrangement has on the total system, are interesting issues to explore. This piece is a still a work-in progress.

I hope to have it completed soon, and I will post some audio examples of this antique technology at work.