Although I don’t necessarily agree with super-aggressive enforcement of certain copyright laws, OR the fact that she tried to sue one of my favorite recording-artists after he released an affectionate tribute-song about her, I don’t want anyone to think that I am hating on Wendy Carlos. Given the remarkable and really uncanny life of this great composer, who can really judge? Pictured above: Carlos with cats and synthesizers.

Although I don’t necessarily agree with super-aggressive enforcement of certain copyright laws, OR the fact that she tried to sue one of my favorite recording-artists after he released an affectionate tribute-song about her, I don’t want anyone to think that I am hating on Wendy Carlos. Given the remarkable and really uncanny life of this great composer, who can really judge? Pictured above: Carlos with cats and synthesizers.

Category: Uncategorized

This Wednesday at BAR in New Haven CT I will be performing as part of Tomorrow Tomorrow, a new group organized around Meredith Dimenna. Tomorrow Tomorrow is the first full-length album that I’ve produced in my new spot Gold Coast Recorders and it is very exciting to be bringing it to life for the first time. Meredith is a truly gifted vocalist and the music is unique hybrid of raw country and psychedelic drone. TT is opening for Daughn Gibson, a fine singer who was been getting acclaim for his new record on the White Denim label. If you’re in the area, come on down; the show is free and Bar serves some of the best pizza in world too.

This Wednesday at BAR in New Haven CT I will be performing as part of Tomorrow Tomorrow, a new group organized around Meredith Dimenna. Tomorrow Tomorrow is the first full-length album that I’ve produced in my new spot Gold Coast Recorders and it is very exciting to be bringing it to life for the first time. Meredith is a truly gifted vocalist and the music is unique hybrid of raw country and psychedelic drone. TT is opening for Daughn Gibson, a fine singer who was been getting acclaim for his new record on the White Denim label. If you’re in the area, come on down; the show is free and Bar serves some of the best pizza in world too.

Diggin

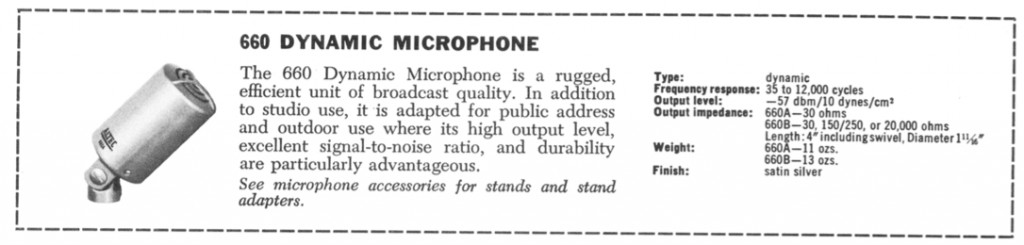

Picked up a few interesting pieces today. Above, an Altec 660B microphone circa 1958. I already had a 660A (same thing, but fixed impedance) but this was too good a deal to pass up. Altec marketed these as ‘broadcast mics’ but both of my units, while having pretty good top end, have a pretty weak bass response. The 660B sounds a little bit better to my ears.

Picked up a few interesting pieces today. Above, an Altec 660B microphone circa 1958. I already had a 660A (same thing, but fixed impedance) but this was too good a deal to pass up. Altec marketed these as ‘broadcast mics’ but both of my units, while having pretty good top end, have a pretty weak bass response. The 660B sounds a little bit better to my ears.

The 660B came mounted on this beautiful Shure S36 tabletop mic stand; that’s a push-to-talk DPDT switch mounted on the front.

The 660B came mounted on this beautiful Shure S36 tabletop mic stand; that’s a push-to-talk DPDT switch mounted on the front.

*******

***

Moving on to stranger fare: above, a “Little Mike” as made by the Brooklyn Metal Stamping Company circa 1930. This one confused me for a minute as it had no markings on it other than a patent date on the rear:

Moving on to stranger fare: above, a “Little Mike” as made by the Brooklyn Metal Stamping Company circa 1930. This one confused me for a minute as it had no markings on it other than a patent date on the rear:

This was enough information to coax Google into revealing the origins of this artifact. See here and here for the details.

This was enough information to coax Google into revealing the origins of this artifact. See here and here for the details.

The Little Mike’s rather long stretch of two-conductor cable terminates in these unusual copper discs. As it turns out, these discs are intended to be attached thru two of the pins on a radio’s detector tube; this will allow the mic signal to come out of the radio speaker.

The Little Mike’s rather long stretch of two-conductor cable terminates in these unusual copper discs. As it turns out, these discs are intended to be attached thru two of the pins on a radio’s detector tube; this will allow the mic signal to come out of the radio speaker.

The question is, naturally: which pins? The grid and the ground-side filament, I assume? I can’t figure out how to get sound out of this thing. I get no DC resistance reading across the two terminals, and no sound when I connect the terminals across a high-gain, high-impedance input. I am guessing, based on the patent date, that this is a single-button carbon mic, which would mean that I would need a low voltage source and a signal transformer that can handle DC on the primary in order to test it. Anyone have any suggestions/advice?

***update: read the comments section for implementation information courtesy of M. Shultz, as well as the not-so-thrilling conclusion to the saga of Little Mike.

1971

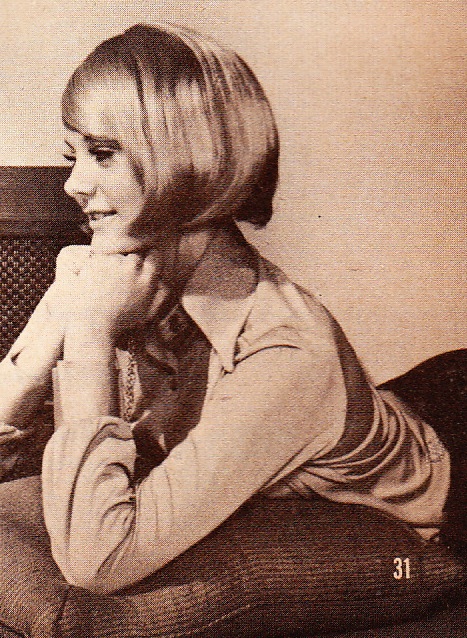

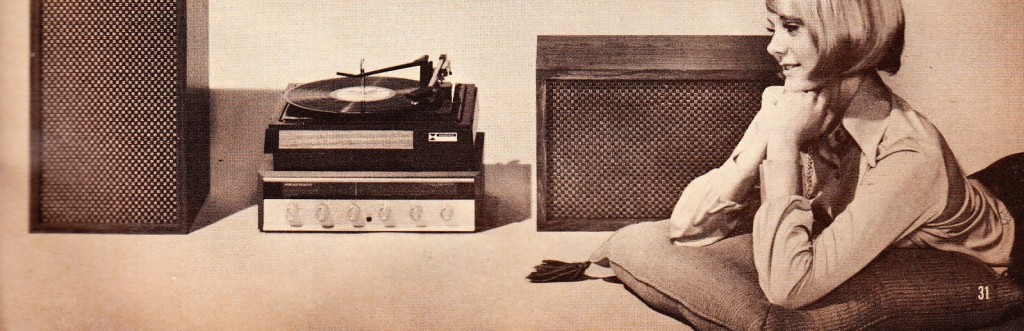

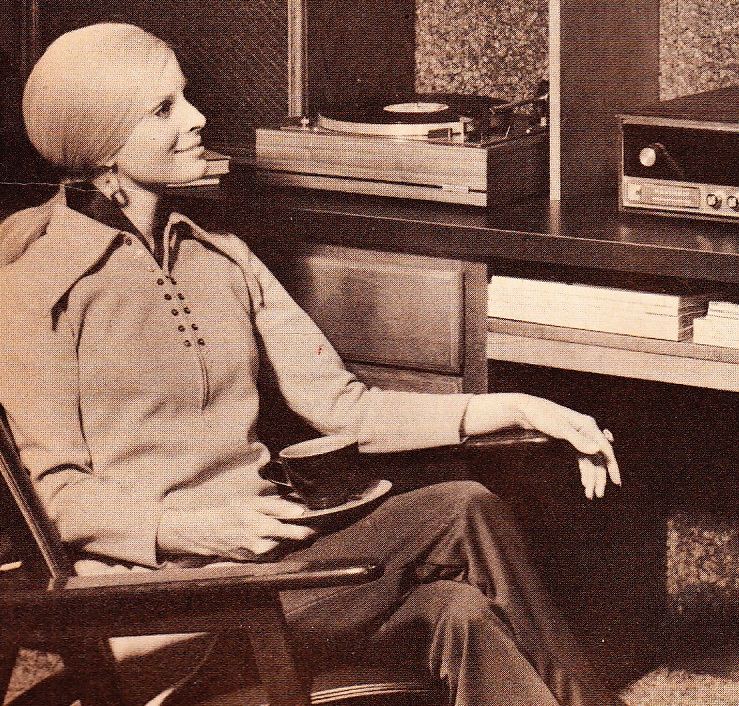

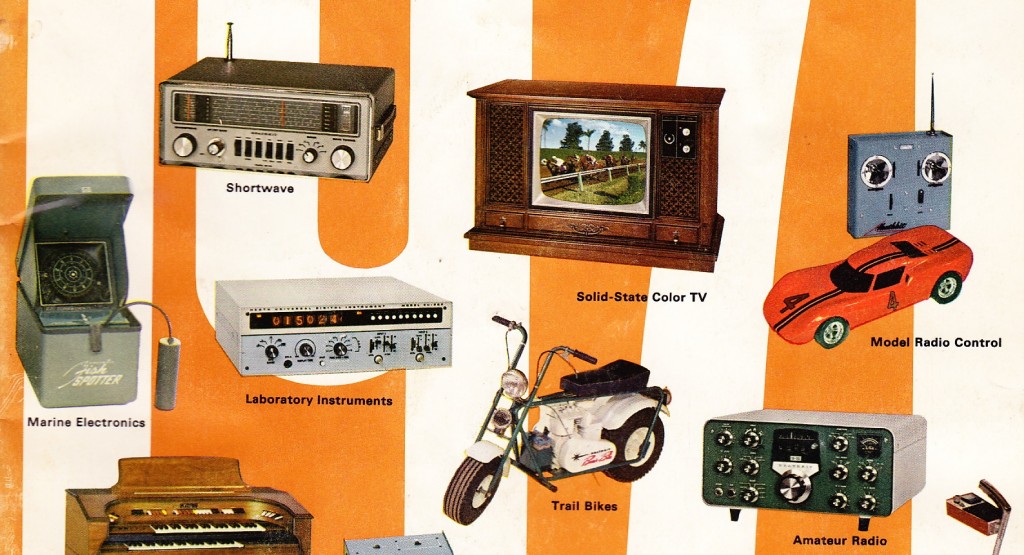

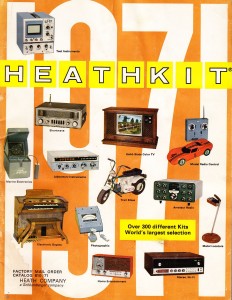

Art dep’t comp for a Wes Anderson film?

Art dep’t comp for a Wes Anderson film?

Nope, it’s the cover of the 1971 Heathkit catalog.

Nope, it’s the cover of the 1971 Heathkit catalog.

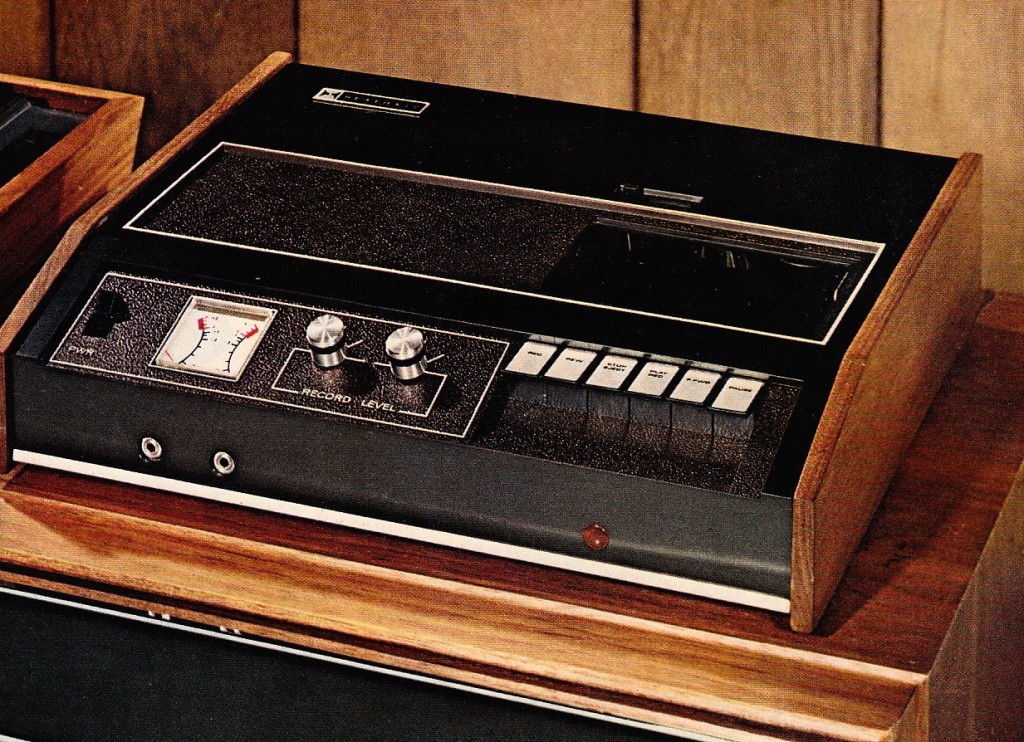

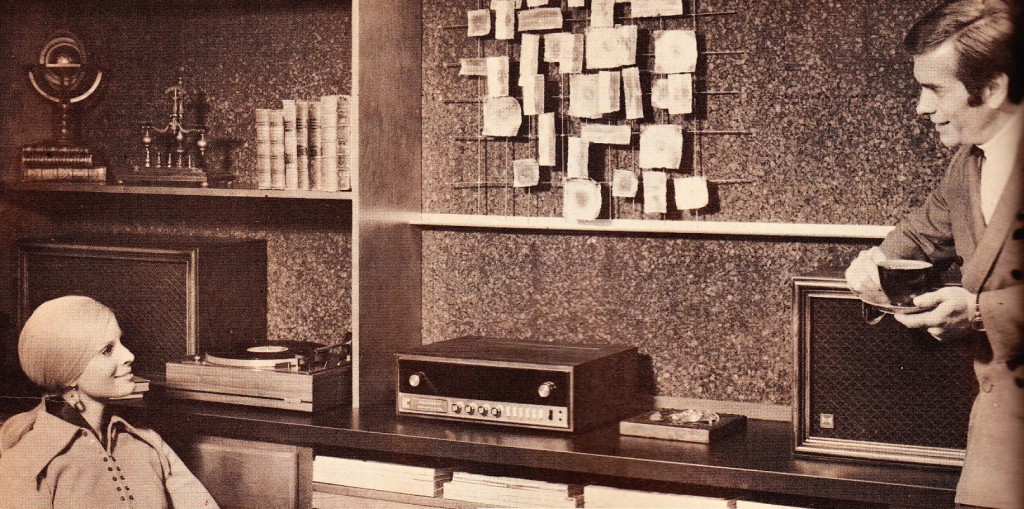

Stumbled upon this, and the accompanying 1971 Heathkit ‘Holiday Catalog’ at a sale today. Nothing too notable on display, but the photography is pretty fantastic. Just watched the latest Wes Anderson pic – his first period picture, I believe – and it struck me that it didn’t feel any different than his other films as far as the wardrobe, propping, and sets. His contemporary characters all seem to hide in the past, at least as far as their chattels are concerned. So heavy is the burden of material culture upon Mr. Anderson. And upon this writer, apparently. Dig in…

Do you remember the beach-times?

Do you remember the beach-times?

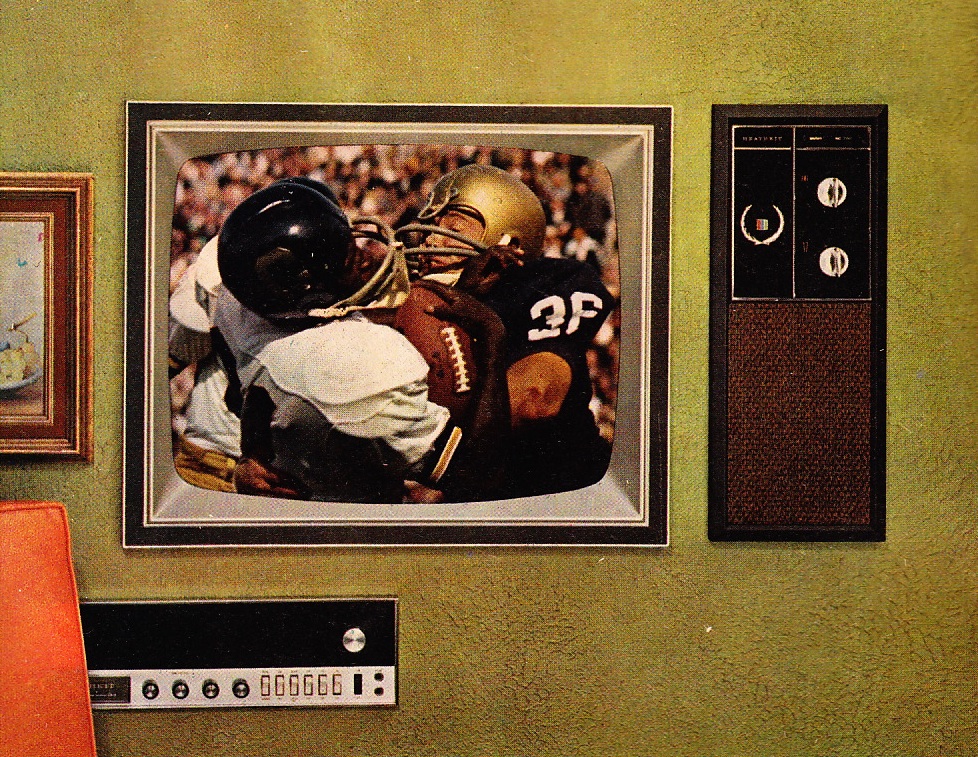

Fukk yr flat-screens. I’m talkin bout in-wall CRTs.

Fukk yr flat-screens. I’m talkin bout in-wall CRTs.

The elusive Tequila Sunrise, miraculously captured indoors

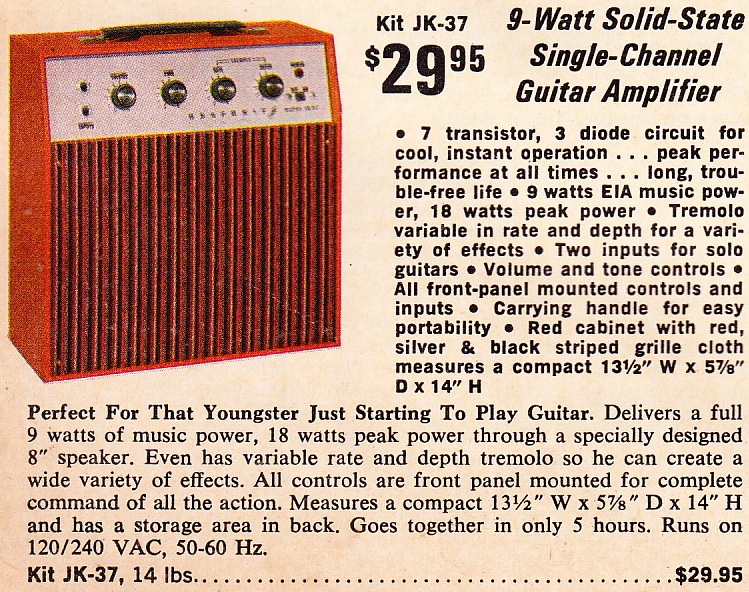

Pictured above: the Heathkit TA-38 bass amplifier and the Heathkit TA-29 and JK-37 guitar amplifiers. Also, your parents.

*************

*******

***

For earlier Heathkit coverage on Preservation Sound dot com, click here.

Genre-branded instruments

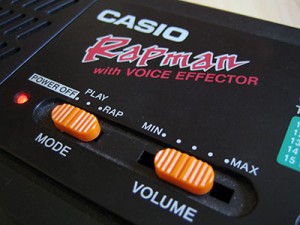

On eBay: a circa 1990 Casio Rap-1 ‘Rapman’ synthesizer/child’s-toy. In its original box with original accessory-microphone; click here and make it yours for $20 plus s+h.

The Rapman (see here for a detailed analysis of its feature-set and cultural positioning) is an early example of the trend to market synthesizers towards performers of specific genres of music. Other notable examples (and there are many more…) include the E-Mu Planet Phatt and Orbit (hip hop and dance, respectively).

The Rapman (see here for a detailed analysis of its feature-set and cultural positioning) is an early example of the trend to market synthesizers towards performers of specific genres of music. Other notable examples (and there are many more…) include the E-Mu Planet Phatt and Orbit (hip hop and dance, respectively).

Above, a recent attempt by an equipment-retailer to genre-fix some of their keyboard wares. A quick scan of the current crop of widely-available synthesizers indicates that there are in fact no actual ‘chillwave-branded’ instruments but nice try anyhow.

Genre-branded guitars are nothing new, of course; above we can see the ‘Gretsch Country-Roc’ circa 1976 and below it a recent ESP something-or-other. Since the electric guitar is generally worn as apparel on-stage and in photographs, its presentational aspect offers ample opportunity for associating it with a specific set of aesthetic and cultural values. On the other hand, how much of a musician’s keyboard (or synth-module) does an audience member ever see? Only the narrow strip at the rear; any free-space there is generally used for overall manufacturer-branding.

Whatever special-value for use in any particular genre of music, therefore, is largely limited to the actual sonics of the keyboard instrument and not its appearance. Attempts to buck this trend have resulted in limited success.

The Keytar, for instance, presents no so much a particular genre-affiliation but rather a desire to celebrate the values of the 1980s.

If you’re curious about the sonic-possibilities of the Casio Rapman, you can gain access to its drum sounds by downloading a free sample-set offered at this website. For the rest of its bounty, you’re just gonna have to drop the $40 or wait for the right yard-sale.

Tape Editing Primer – part 2

The Alice 62/3B broadcast console circa 1977. No relation to the subject of this article….

The Alice 62/3B broadcast console circa 1977. No relation to the subject of this article….

Following our earlier post of DB magazine’s excellent 1976 tape-editing primer: the 1977 followup. Download it here…

DOWNLOAD: dB-7702-CBS_Radio-Art_of_Tape_Editing-followup

Many great insights in this piece as well. Good reading for anyone who’s work requires any sort of audio editing.

To read part one, click here…

Above: Mato (drums) and Jon (seated) during drum tracking. Recognize the space? If so, you are one of the 12 people who saw this cinematic debacle, filmed largely in this very building.

Above: Mato (drums) and Jon (seated) during drum tracking. Recognize the space? If so, you are one of the 12 people who saw this cinematic debacle, filmed largely in this very building.

Several years ago, before I had Gold Coast Recorders, I had a modest recording-studio setup in the former American Fabrics factory on the east side. It was a small operation with a large control room and two small ‘booths’ with observation windows linking all the spaces. Nothing fancy, but I did manage to make a number of successful productions there. NEways… due to the very small size of the tracking rooms I sometimes resorted to tracking after-hours and on weekends in other parts of the floor. A few tracks from one of my final sessions there were recently released.

Have a listen to “Brass Bonanza,” the lead-off track from Five Minute Major (In D Minor), the latest album by The Zambonis. The record was released in February 2012 to great response from The New Yorker, The Examiner, and NPR.

Have a listen to “Brass Bonanza,” the lead-off track from Five Minute Major (In D Minor), the latest album by The Zambonis. The record was released in February 2012 to great response from The New Yorker, The Examiner, and NPR.

LISTEN: Brass Bonanza

Horn tracking space for “Brass Bonanza.”

Horn tracking space for “Brass Bonanza.”

I love Pro Tools. I’m not afraid to say it. I love the convenience, the low cost, the rapid editing ability, the fact that it leaves essentially no limits to music production other than the imagination and the skill of the artists/engineer. And while I tend to use plug-ins (audio-processing sub-programs that run within the pro tools software body) for more corrective rather than creative purposes, preferring to ‘get-the-right-sound-on-the-way-in,’ I don’t have many issues with how they sound either. The one thing, the one little thing that I can’t quite fall-in-with, though, is digital reverb.

Back in the ole’ days when I used a Yamaha Rev7 and ADATs I really did not mind the sound of digital reverb; the recording media was lower-resolution, the Rev7 was 12-bit and had much less high-frequency content to begin with, and I was certainly less critical of a listener. In my current set-up of Pro Tools HD3 with Lynx convertors and a properly tuned control room, though, I just can’t seem to fool myself into thinking that the digital reverb plug-ins effectively create the sound of an actual space. Not that this is the only possible function of reverb; reverb is also useful for smoothing out pitch issues and simply creating multiple planes of depth within a sonic field. But when I’m recording a rock band, trying to capture the energy and volume of a performance, I feel like it does the band the most justice to ‘put it in a space.’ And what better space than real space? In the case of ‘Brass Bonanza,’ there was no artificial reverberation used. The drums were tracked in the space that you see them in: approximately 30% of the way along a 100-foot hallway. The horns were tracked in the tiled restroom that you see, with the single ribbon mic depicted in the photo. How much additional value/merit does this give to the recording versus running a reverb plug in? That’s up to you to decide. The band wanted a very reverberant sound and the only way that I can be satisfied with heavy reverb is if it has some if the complexity, texture, and non-linearity that a real space offers.

So what do you do if you don’t have a 100-foot hallway or an 1100-sq ft live room to track drums in? I’ll begin with some advice given to me several years ago by the great producer Martin Bisi. I was subletting studio space from Martin at the time and in one of our many wonderful conversations Martin offered me this bit of wisdom which I paraphrase for you here. Life is complex; reality is complex. What we experience in the world is complex. The more sonic complexity you introduce into a recording, the closer you come to recreating actual lived experience. I hesitate to say “you make it life-like,” since this is ultimately not possible, but you get closer to that impossible goal.

So if this is true, what does it mean for process? Well, first of all, notice that there is no mention here of musical complexity. We’re talking about adding sonic interest to a musical performance. This ultimately holds the promise of allowing us to simplify and streamline the musical lines/performances while still creating and maintaining a huge amount of interest for the listener. With enough detail, care, and complexity achieved in the audio rendering of a musical performance, even the most utterly simple melody, phrase, line, or note can create incredible meaning. This is the most basic, and the most profound, goal of creative audio engineering.

Second, but no less important, is this idea that perhaps it is the complexity of the sonic-event, and not necessarily any verisimilitude to any actual acoustic even/space, that really matters most. So while I may have coveted the sound of that long hallway and that super-reflective restroom, perhaps what I really gain from those sonic generators is the infinite amount of complexity that they bring to the sound, and not necessarily the fact that I think the qualities of actual physical space are accurately described in the mix. Here’s something you can try at home. Create your mix using whatever digital reverb tools you have. Print the output of the reverb as an audio stem. Solo that stem. Find the space in your house/apartment/studio that has the most interesting sonic quality and a pleasing frequency-response character. Put your monitor speakers and a stereo pair of mics in that space and re-amp the reverb stem only. Record that to its own stereo track. You have now added an infinite (within the limitations of the A/D convertors) amount of complexity to a digital reverb that is, necessarily, somewhat limited in detail. See if this new, 2nd-generation reverb adds interest and complexity to the mix. You will probably need to EQ it a bit, but you can do this fairly easily by using the first-generation digital print as a guide. Consider using this 2nd gen reverb as perhaps a ‘spotlight’ reverb for the ld vox, chorus snare drum, or percussion stem. When we re-orient our awareness to the problem/promise of complexity in sound-recordings rather than fidelity, great things can and will happen.

You can learn more about The Zambonis and stream their new record at TheZambonis.com. “Brass Bonanza” and “Fight On The Ice” are my two productions on the record; the rest of the album was produced and engineered by the great Peter Katis and Greg Giorgio at the world-renowned Tarquin Studios, also located in scenic Bridgeport Connecticut.

Tomorrow, 5.11.12, I’ll be a guest on Del’s “In Transition” show in the eight o’clock hour. We’ll be listening to some recent productions I’ve put together at Gold Coast Recorders and talking shop about music, audio, love, loss, and life. In addition to being a radio host and rocknroll aficionado Del is a veteran audio tech with a long resume that includes many of the greatest recording studios in NYC. So it promises to be an interesting chat. Listen in at 8AM tomorrow EST at 89.5FM in the New York Metro Area or stream it live at www.wpkn.org.

Tomorrow, 5.11.12, I’ll be a guest on Del’s “In Transition” show in the eight o’clock hour. We’ll be listening to some recent productions I’ve put together at Gold Coast Recorders and talking shop about music, audio, love, loss, and life. In addition to being a radio host and rocknroll aficionado Del is a veteran audio tech with a long resume that includes many of the greatest recording studios in NYC. So it promises to be an interesting chat. Listen in at 8AM tomorrow EST at 89.5FM in the New York Metro Area or stream it live at www.wpkn.org.

UPDATE: This segment has aired and can now+forever be streamed from the WPKN archive. Click on this link to listen. My bit comes in around the sixty-minute mark. One correction: in the piece I state that my tenure at SONY began in 1991; this is not correct. I started in 2001. Blame it on the A – M.

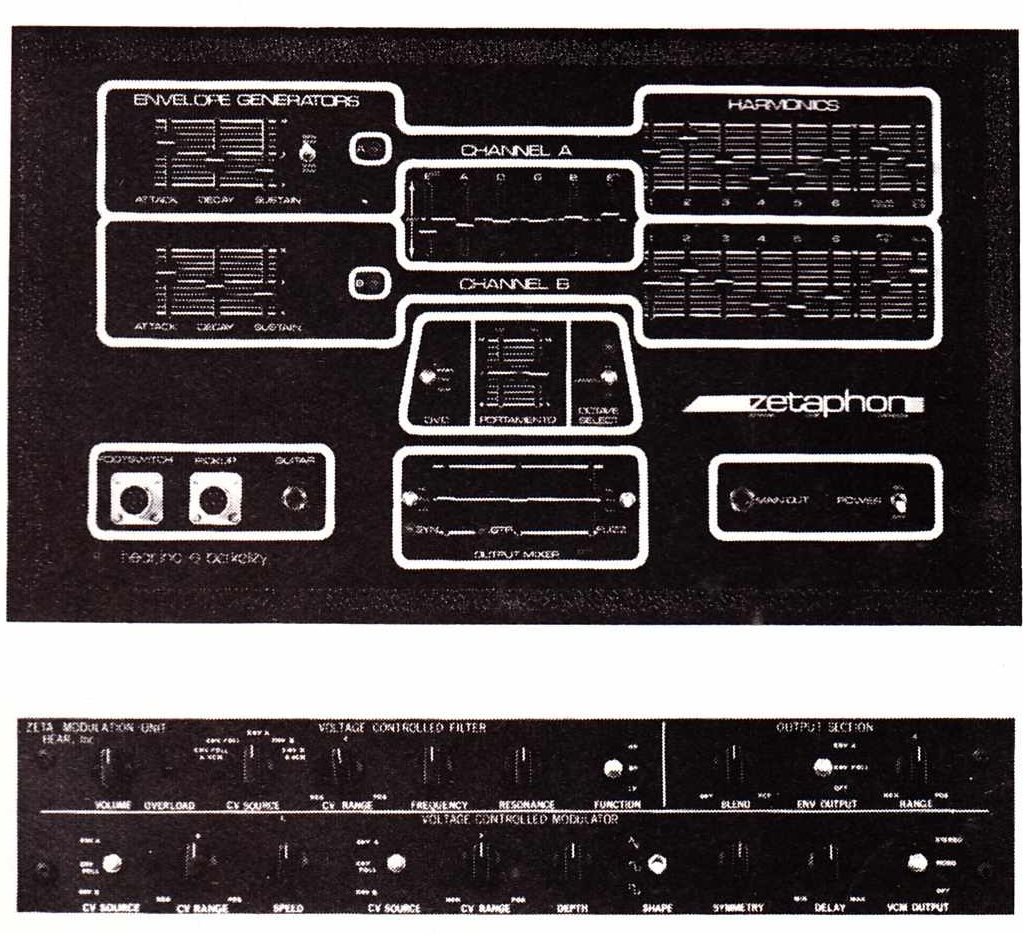

Guitar Synths of the late 1970s

Today as PS dot com: a quick look at the then-new product-category of Guitar Synths circa 1979. A great number of small manufacturers sprung up to offer these devices, and a few of the big names got involved as well. What is required for a guitar synth? Well, at minimum, independent pitch-to-CV and envelope-to-gate tracking and conversion for each of the six strings, and then some sort of synthesis engine (x6) to create the actual sound that you hear. Some of the units covered in this post were only the first part of the equation, and you could certainly find monophonic pitch/gate-to-CV modules going back to the early 70s (anyone know the release dates of the specific Moog and ARP modules that did such?). But putting it all together in a package that a guitar player might want to buy: this took some time. Guitar synths never really caught on, probably due to the cost initially, but even as prices came down it really seems like the vast majority of players were just happier with a bunch of effects pedals. In addition, there is something inherently retrograde with performing on the electric guitar regardless; it is very much a signifier of the 1950s and 1960s; so why muddy the waters of yr joyous celebration of the past with so much technology?

If anyone is still using any of these things on-stage or in productions, drop a line and let us know…

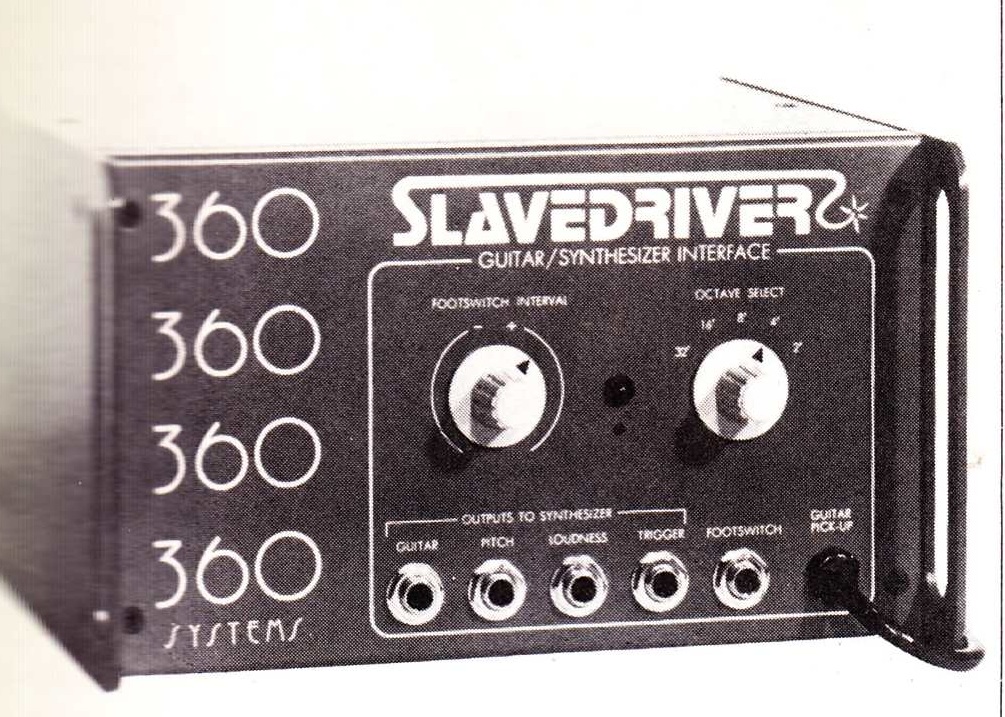

The Slave Driver, also from 360 Systems

The Slave Driver, also from 360 Systems

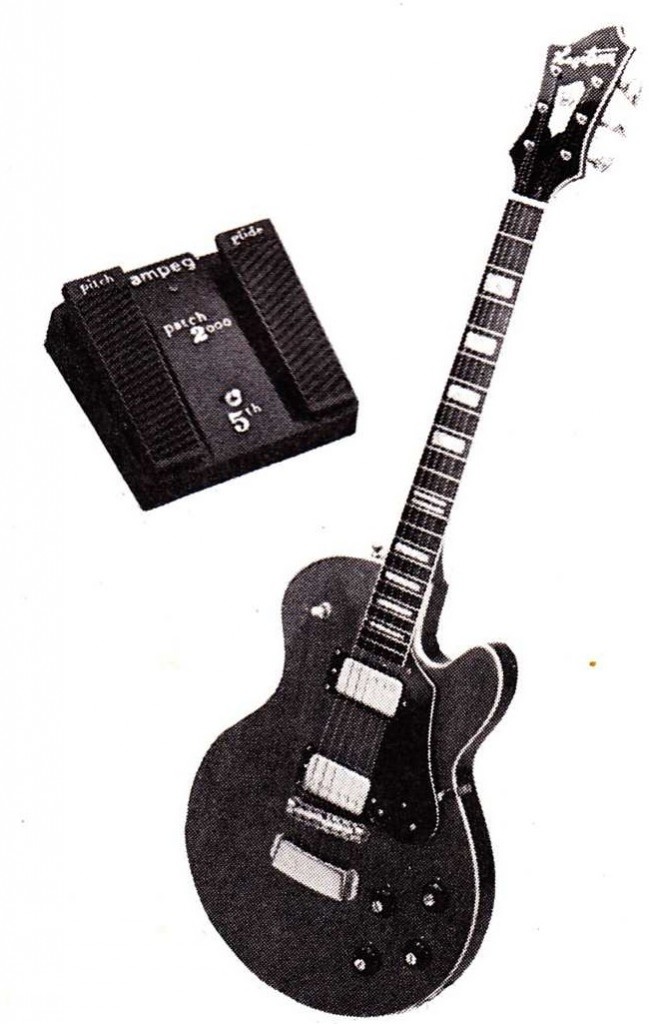

The Ampeg Patch 200: Note Hagstrom-Swede.

The Gentle Electric (love that name…) model 101 pitch/envelope follower

The Gentle Electric (love that name…) model 101 pitch/envelope follower

The Polyfusion FFI frequency follower. Click here for previous Polyfusion coverage at PS dot com.

The Polyfusion FFI frequency follower. Click here for previous Polyfusion coverage at PS dot com.

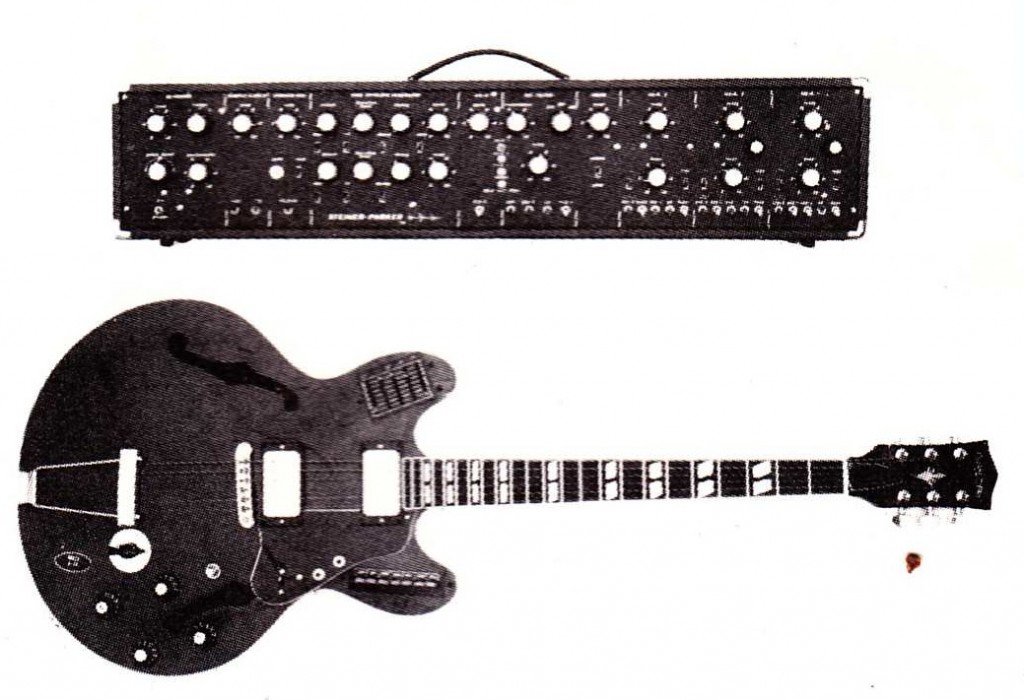

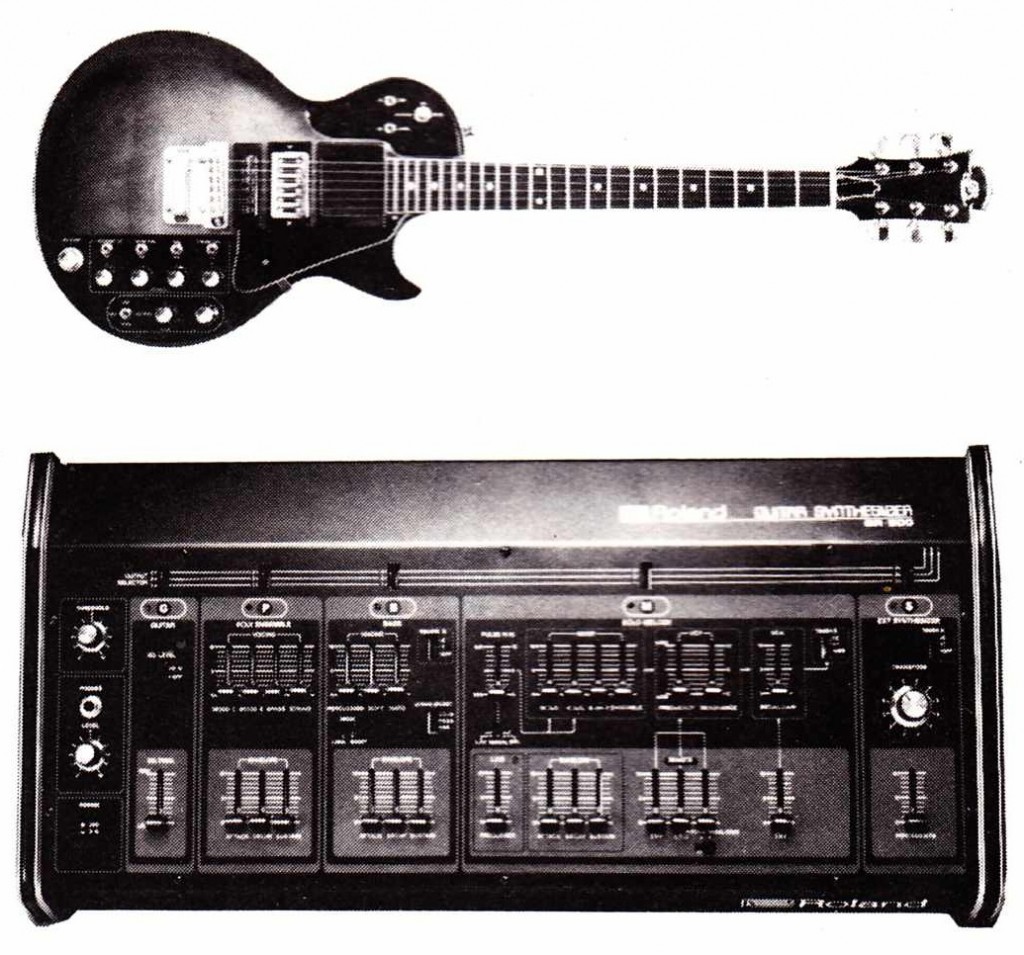

The Roland GS500 and GR500: early products in a line that is still being produced today, over 30 years later.

The Roland GS500 and GR500: early products in a line that is still being produced today, over 30 years later.

![]() The mighty ARP Avatar. Below, a period advert…

The mighty ARP Avatar. Below, a period advert…

![]() …and click here to view the same-period ARP full-line catalog available for download at PS dot com.

…and click here to view the same-period ARP full-line catalog available for download at PS dot com.

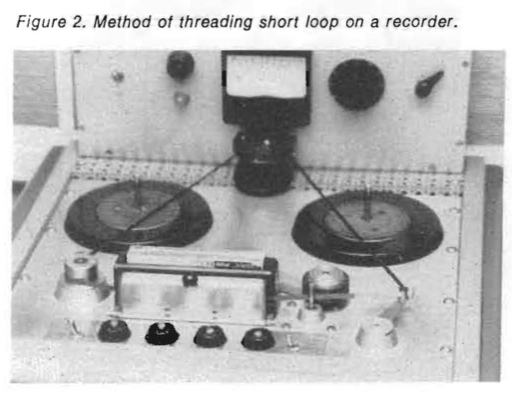

Download a five-page article by Mortimer Goldberg as first published in DB magazine, 12/76:

Download a five-page article by Mortimer Goldberg as first published in DB magazine, 12/76:

DOWNLOAD:dB-7612-CBS_Radio-Art_of_Tape_Editing

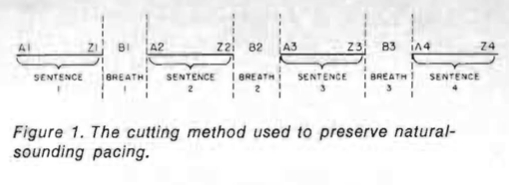

Many thanks to T.F. for sending us this wonderful piece. Anyone who is involved with editing audio or video should give this a read. Goldberg gives an explanation of what goes into making ‘natural’ sounding dialogue edits, and my god he’s really got it down to a science.

Goldberg was a technical supervisor for CBS for over a quarter-century, and everything that he offers here is still very applicable to modern DAW production. I was fortunate enough to learn these techniques first-hand from some of the wonderful audio-post engineers at the now-vanished SONY Music Studios in Manhattan, and the applications extend way beyond dialogue and into music production. Even if you never do audio-post work, remember that our minds are incredibly attuned to human speech; if you can learn to make perfect, in-detectible speech edits, your music edits will follow suit. Also notable: Goldberg offers a very insightful account of why the critical demands of Radio speech-editing are far greater than similar work for Television production. Great stuff.

Goldberg was a technical supervisor for CBS for over a quarter-century, and everything that he offers here is still very applicable to modern DAW production. I was fortunate enough to learn these techniques first-hand from some of the wonderful audio-post engineers at the now-vanished SONY Music Studios in Manhattan, and the applications extend way beyond dialogue and into music production. Even if you never do audio-post work, remember that our minds are incredibly attuned to human speech; if you can learn to make perfect, in-detectible speech edits, your music edits will follow suit. Also notable: Goldberg offers a very insightful account of why the critical demands of Radio speech-editing are far greater than similar work for Television production. Great stuff.

BTW, I have not been able to find any other issues of this particular ‘DB Magazine’ (as you might imagine, many publications have been offered under this title). The full title seems to be “DB The Sound Engineering Magazine” and fwict it was published between 1968 and 1984. Anyone know where I can get some back issues for a good price? eBay is asking $14.95 an issue…