Download the fifty-page 1940 PRESTO RECORDING CORP catalog:

Download the fifty-page 1940 PRESTO RECORDING CORP catalog:

DOWNLOAD (part 1): Presto_1940_Cat_1

DOWNLOAD (part 2):Presto_1940_cat_2

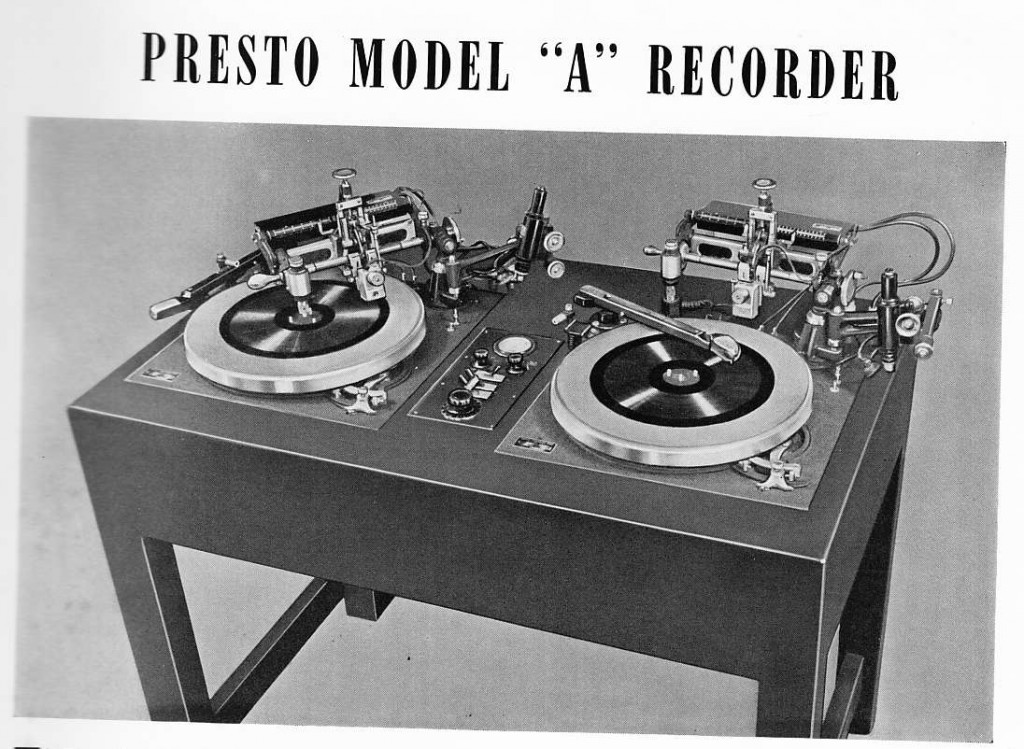

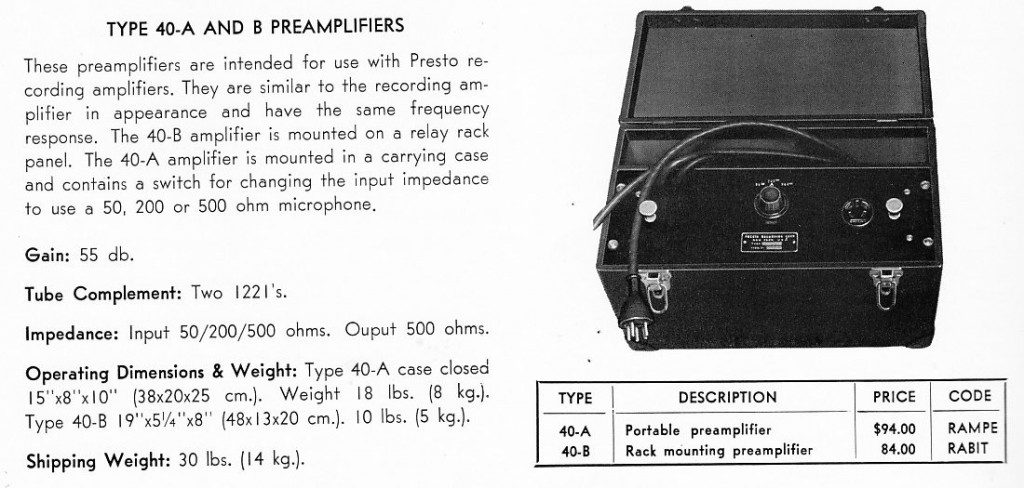

Products covered, with text, some specs, and photos, include: Presto Model A, Model B, Model F recording installations; Presto Model C, Model Y, and Model K portable recorders; Presto type 8-A, 8-B, 28-A, 6-D, 6-E, 6-F, 26-B, 75-A, 75-B, 75-C, 9-A, and 9-B recording turntables; Type 62-A transcription turntable; Automatic Equalizer 160; blower system 400; 150 and 151 pickups; Microphone Mixer type 130-A, B, C; Preamplifier type 40-A and 40-B; Presto radio tuner 50-A and 50-B; Recording Amplifiers 85-A, B, 85-E, 87-A and 87-B; plus a range of parts and accessories including Green Seal discs, Orange Seal discs, and Blue Label discs.

Above, the Presto Model A, their top-of-the-line system circa 1940.

Above, the Presto Model A, their top-of-the-line system circa 1940.

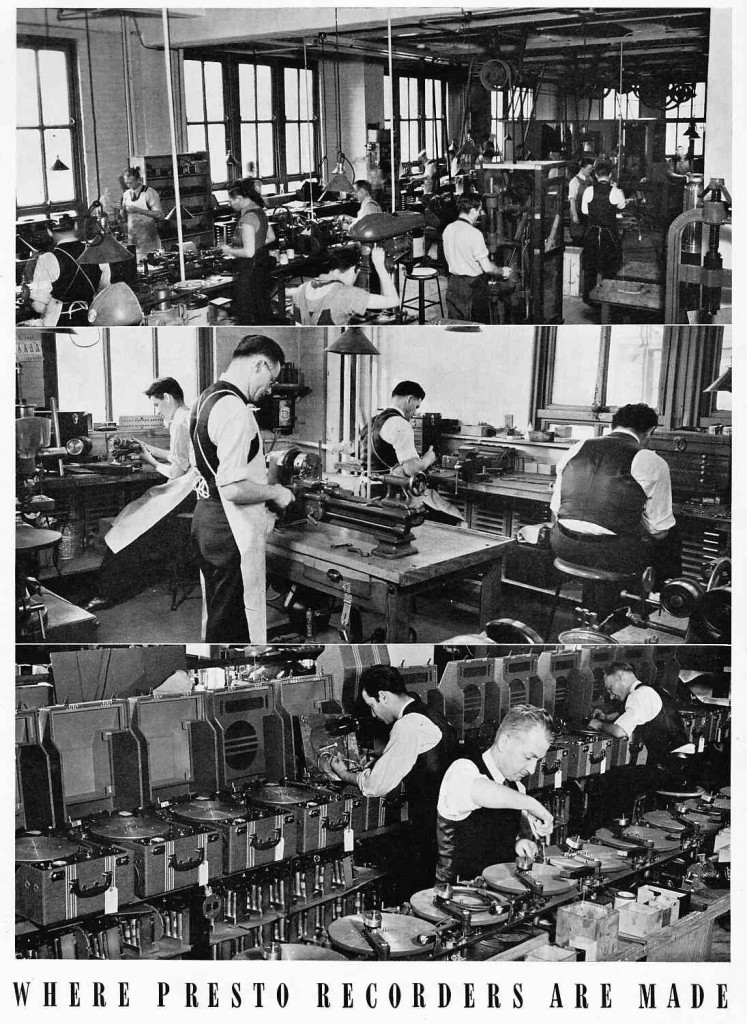

Presto Recording Corp was a pioneer of coated-disc ‘Instantaneous Recording.’ From 1933 through the end of WWII, Presto was the US leader in providing high-quality recording equipment to broadcasters, schools, studios, and government. There is a detailed history of the Presto Corp provided at this website, so no need to re-tread those waters. Basically, what Presto offered was a way to make good-sounding LP and 78 recordings that could be played back instantly on any home turntable. Unlike earlier commercial recording technologies, there was no intermediate submaster required. Presto was able to do this by having designed an aluminum (later, glass) disc that was coated with a special cellulose-based compound (featuring 51 ingredients!).

At right, the Presto 200-A Electronics package. This was a complete system of microphone preamps, cutting amps, patchbay, and AM radio tuner that was designed to accompany the Model-A pictured above. Presto’s ‘instant-disc’ technology was basically rendered obsolete by the development of magnetic tape recorders in the late 1940s, most notably, AMPEX (and to lesser degree, Magnecord). The specs for the better Presto systems weren’t awful: 50-8000hz frequency range, 50db signal-to-noise ratio; but this paled in comparison to the German Magnetophon technology that AMPEX built on, with a high-frequency response to 15,000hz.

At right, the Presto 200-A Electronics package. This was a complete system of microphone preamps, cutting amps, patchbay, and AM radio tuner that was designed to accompany the Model-A pictured above. Presto’s ‘instant-disc’ technology was basically rendered obsolete by the development of magnetic tape recorders in the late 1940s, most notably, AMPEX (and to lesser degree, Magnecord). The specs for the better Presto systems weren’t awful: 50-8000hz frequency range, 50db signal-to-noise ratio; but this paled in comparison to the German Magnetophon technology that AMPEX built on, with a high-frequency response to 15,000hz.

On a more basic user-level: you could always record-over a piece of magnetic tape; but cutting into a lacquer-coated disc (at $16/unit in today’s money) was a commitment.

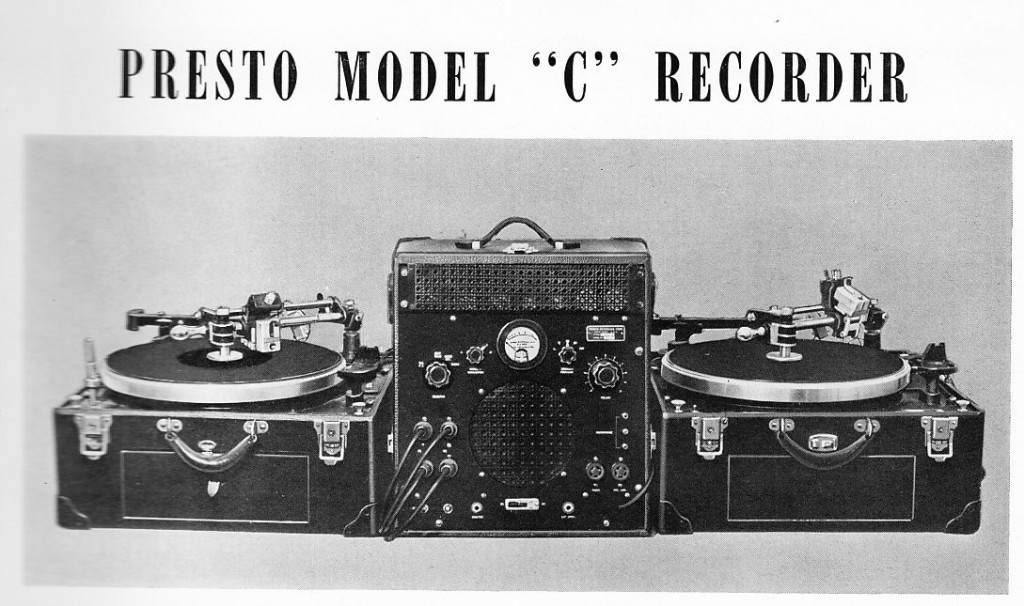

Presto Model C, their top-end portable system of 1940 ($20,000 in 2011 dollars; 138 lbs)

Presto Model C, their top-end portable system of 1940 ($20,000 in 2011 dollars; 138 lbs)

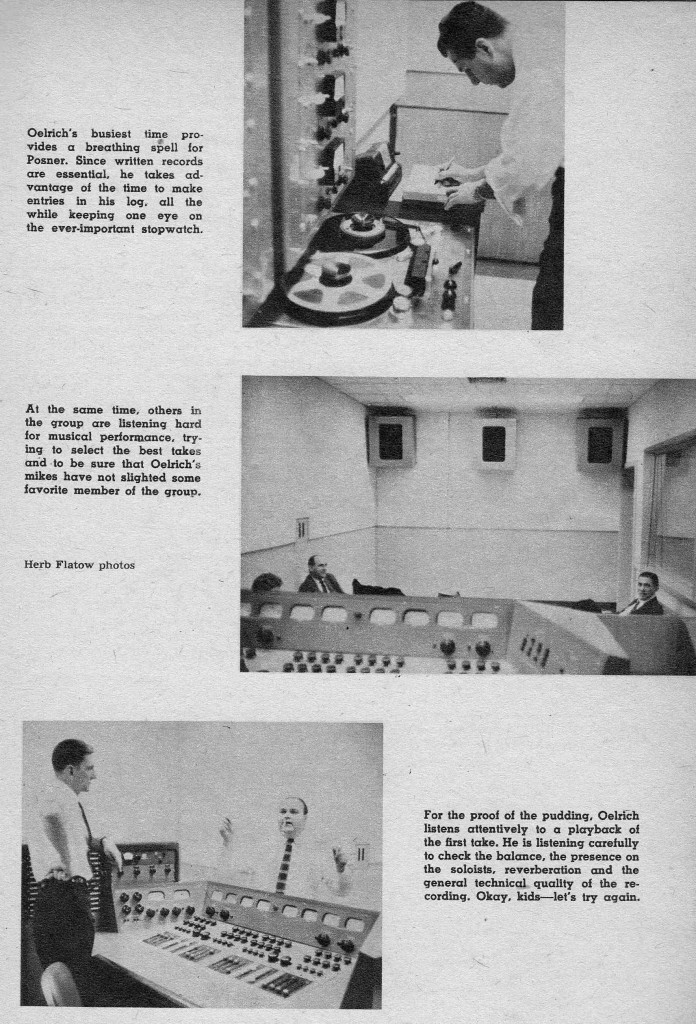

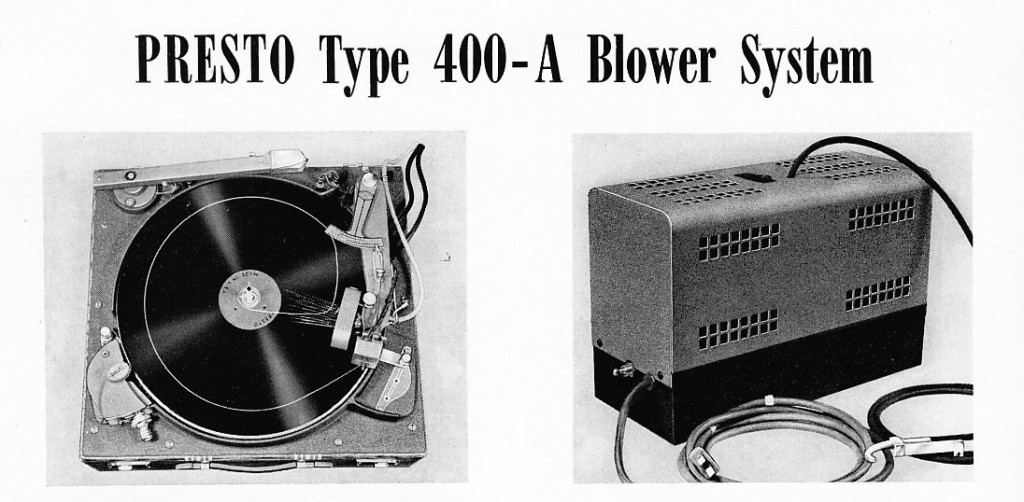

Looking through this catalog, the most fascinating aspect is the large range of mechanical devices and accessories recommended to insure the fidelity of the audio. Nowadays almost all audio control happens electronically; once the room is treated and the microphone carefully placed, our work as recording engineers leaves the realm of physical manipulation and enters a world of electronic control. In the era of analog disc recording, though, a careful recording engineer needed blowers…

…to efficiently remove the bits of cellulose material that the cutting needle carved out the the recording blanks;

…to efficiently remove the bits of cellulose material that the cutting needle carved out the the recording blanks;

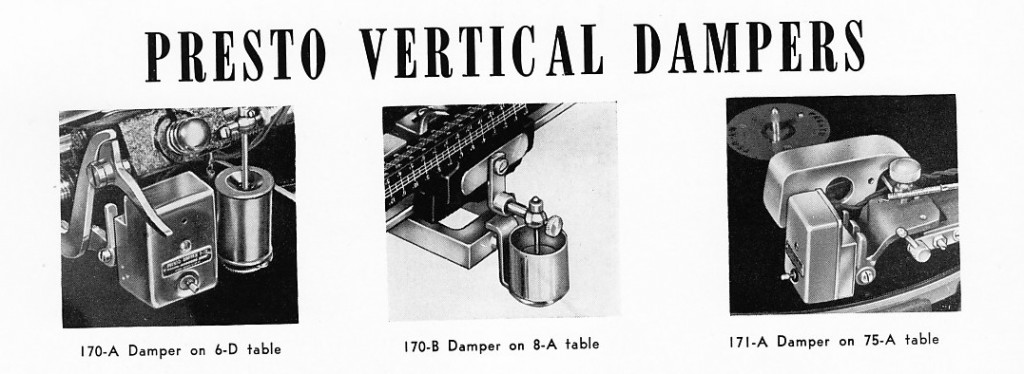

viscous-oil-filled dampers to regulate vertical movement of the cutting head (a mechanical audio compressor, I would imagine);

viscous-oil-filled dampers to regulate vertical movement of the cutting head (a mechanical audio compressor, I would imagine);

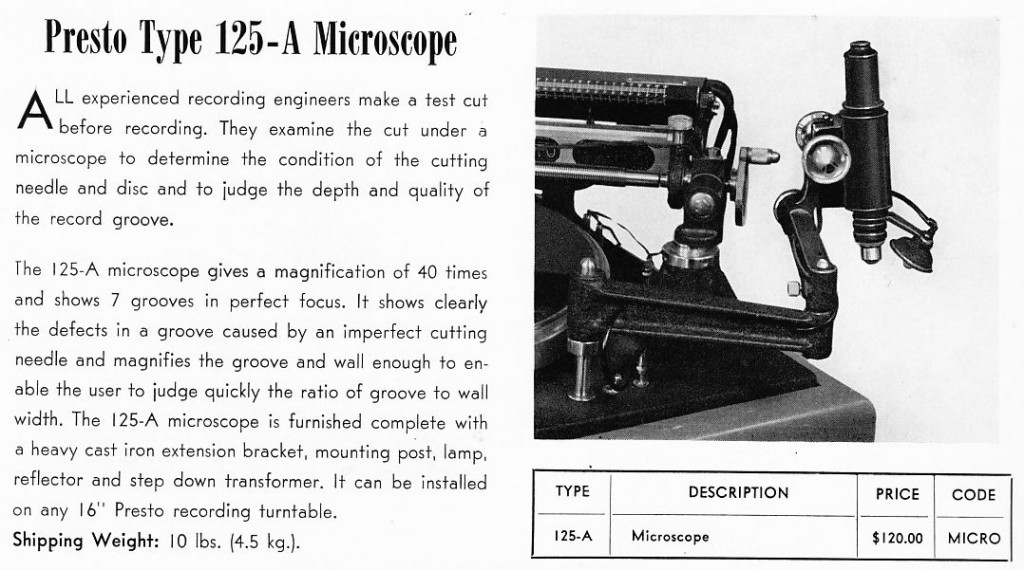

…an optical microscope to examine the grooves that you just cut for quality-control purposes…

…an optical microscope to examine the grooves that you just cut for quality-control purposes…

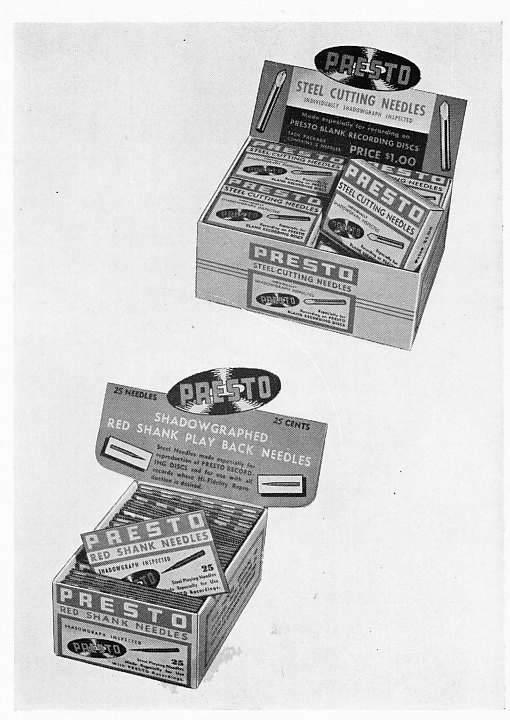

fresh sharp needles to do the actual cutting work…

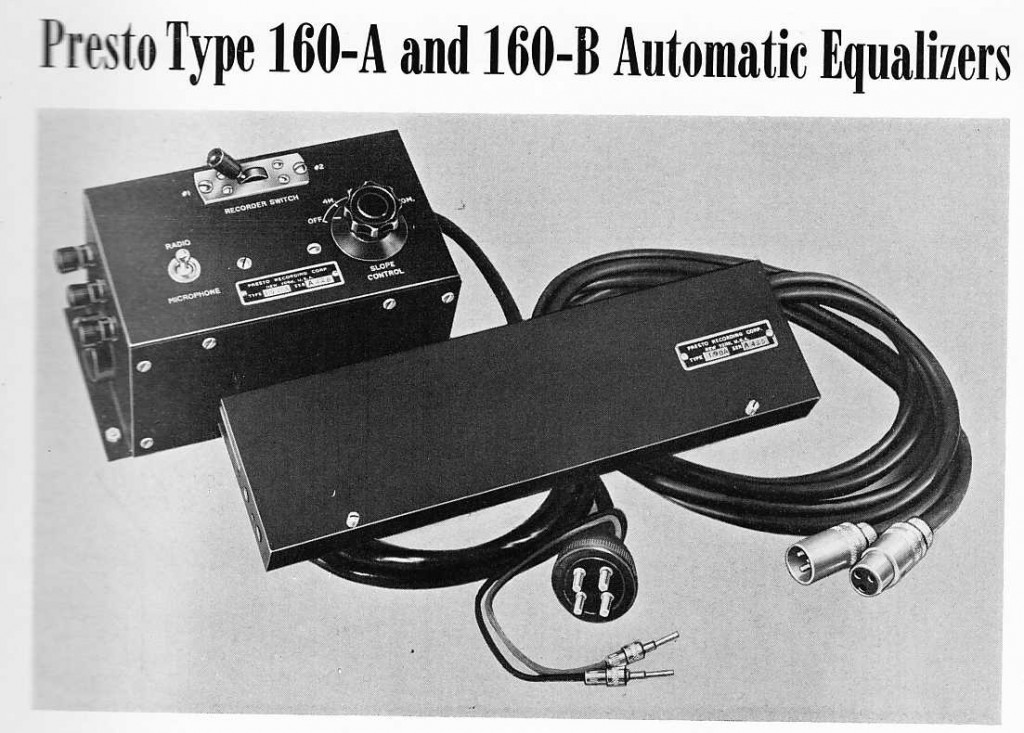

fresh sharp needles to do the actual cutting work… and, if you wanted the ultimate in convenience, an ‘automatic equalizer’ to automatically boost the treble frequencies as the cutting head moved closer to the center of the disc (since discs spin at a constant rate, as the needle gets closer to the center of the disc, the actual linear speed of the needle relative to the surface medium gets slower, and as we know well in all types of analog recording, slower equals less high-end).

and, if you wanted the ultimate in convenience, an ‘automatic equalizer’ to automatically boost the treble frequencies as the cutting head moved closer to the center of the disc (since discs spin at a constant rate, as the needle gets closer to the center of the disc, the actual linear speed of the needle relative to the surface medium gets slower, and as we know well in all types of analog recording, slower equals less high-end).

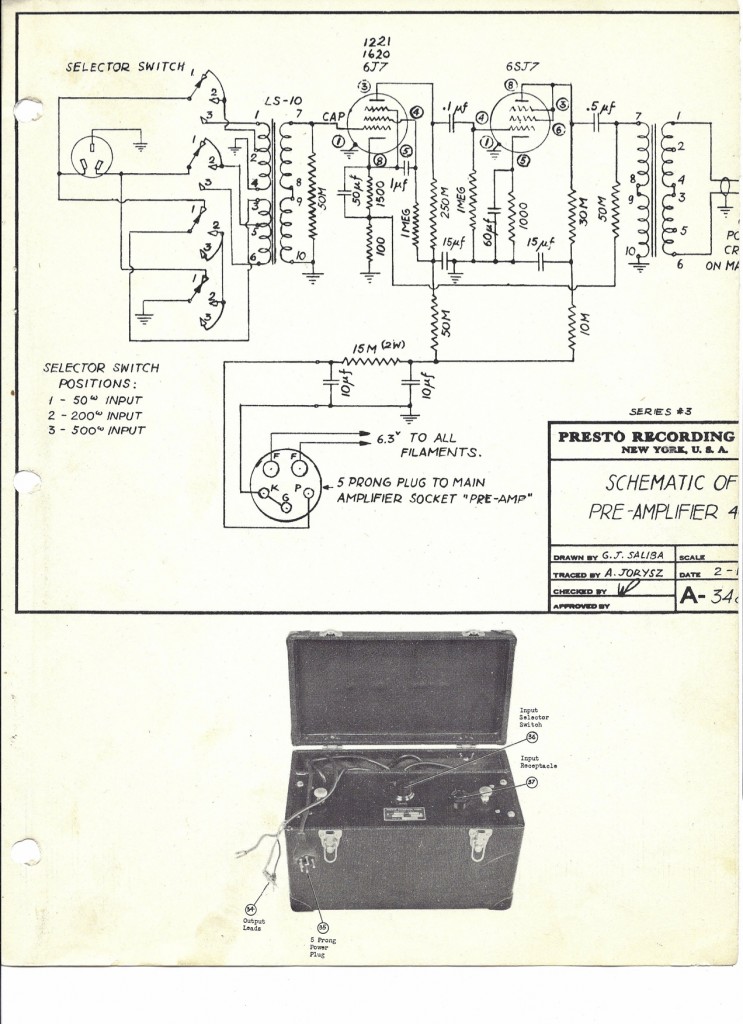

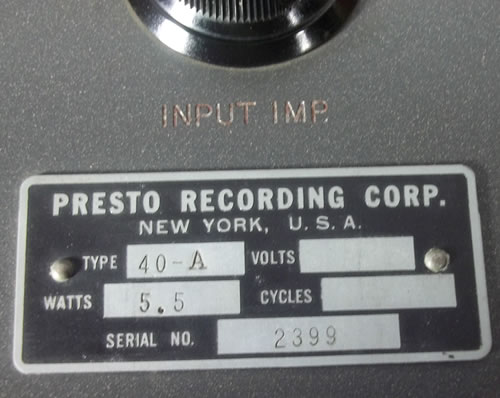

Above, the Presto 40-A microphone pre-amplifier, the one piece of equipment in this lengthy catalog that could still be of potential use to modern recordists. It uses two 1221 tubes to deliver 55dbs of gain (from what I can gather, 1221s are interchangeable with 6C6, the 6C6 being the predecessor to the 6J7, likely making these 40As likely very similar to RCA BA1/2/11 series mic preamps). If anyone has the schematic to the Presto 40 mic preamp, please send it to us… coincidentally I built a preamp with 6C6s a few years ago (based on a schematic from an ancient UTC catalog) and I liked the results.

Above, the Presto 40-A microphone pre-amplifier, the one piece of equipment in this lengthy catalog that could still be of potential use to modern recordists. It uses two 1221 tubes to deliver 55dbs of gain (from what I can gather, 1221s are interchangeable with 6C6, the 6C6 being the predecessor to the 6J7, likely making these 40As likely very similar to RCA BA1/2/11 series mic preamps). If anyone has the schematic to the Presto 40 mic preamp, please send it to us… coincidentally I built a preamp with 6C6s a few years ago (based on a schematic from an ancient UTC catalog) and I liked the results.

UDPATE:

Thank-you to reader EL for sending us the schem to the Presto 40-A. Here ’tis as a download: PRESTO Type 40-A preamp schematic

…And here as well:

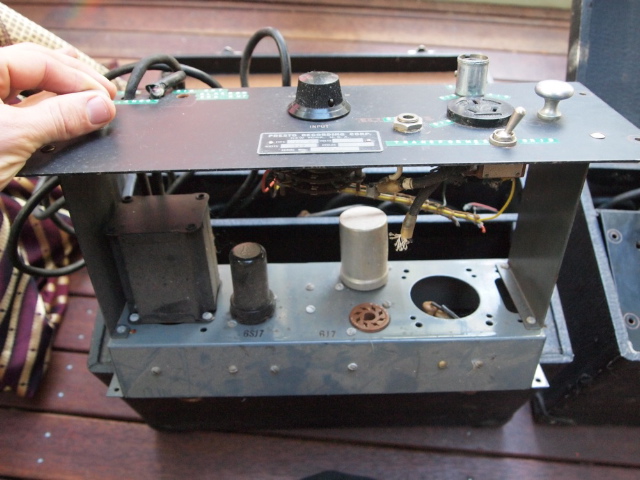

This must be a slightly later version of the 40-A, as the 2nd tube is a 6SJ7, which is a variant of the 6J7 that has the input grid connection in the base rather than on the top. Other things to note: the input transformer spec’d is an ‘LS-10,’ which I can only assume means the UTC LS-10… circuit-wise, we have the first 6J7 connected in pentode, coupled by a .1uf cap to the 2nd 6SJ7 stage, this time wired in Triode in order to more easily drive the output transformer. A ’50M’ resistor (or as we know them, 50K ohms) provides negative feedback from stage 2 to stage one. Thinking that this circuit could be nice as the back end to a 3-stage pre, maybe with a something low-gain like a 76 or 6J5 on the front end with a volume pot following.

UPDATE (2)

EL also provided some images of his particular 40A units… check ’em out…

Pretty amazing that these things made it all the way to Australia way back when… my lord can you imagine how much these things must have cost in their day?

Pretty amazing that these things made it all the way to Australia way back when… my lord can you imagine how much these things must have cost in their day?

***********

*******

***

*

*************

*******

***

Update Sept 2013:

E.L. directed us to this eBay auction; a Presto 40a in nice condition (Nashville, TN) sold for $510. Here are some images:

*******

***

Anyone out there using any Presto equipment in their work? Drop a line and tell us about it….

UPDATE: a friend has alerted us to The 78 project, a series of new recordings of notable musicians made using just a Shure 51 mic and a Presto disc recorder. They sound great, and in the videos you can hear both the modern production-sound of the session via the camera audio-track and the actual 78 playback. Very interesting contrast…