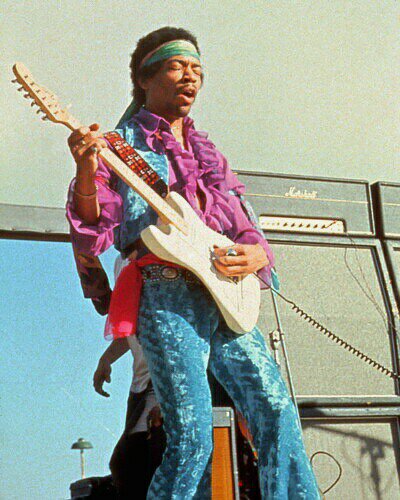

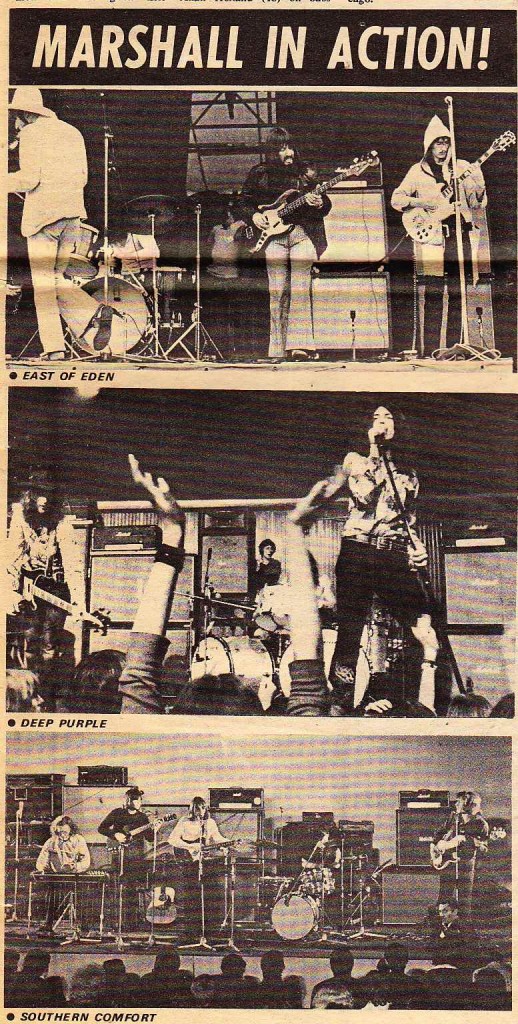

What greater visual icon for the mythic virility and power of the circa-1970 Rock-Star than the “Marshall Stack?”

Jim Marshall was a drum-shop keeper in London in the mid-60’s who began cloning the 1959 Fender Bassman amplifier in order to give British Musicians the popular American-Amplifer sound they wanted at a lower price made possible by domestic UK manufacture.

By around 1968 he had arrived at the classic Marshall formula of a simple Fender-derived circuit using 4x EL34 output tubes, Drake transformers, and a head unit sitting atop 2 large sealed cabinets each holding four 12-inch speakers. It is the use of the EL34 tubes (rather than Fender’s 6L6s) , with their greater power and gain, along with the ‘tight’ bass response afforded by the large speakers in the sealed boxes, that are most responsible for the ‘Marshall’ sound.

By around 1968 he had arrived at the classic Marshall formula of a simple Fender-derived circuit using 4x EL34 output tubes, Drake transformers, and a head unit sitting atop 2 large sealed cabinets each holding four 12-inch speakers. It is the use of the EL34 tubes (rather than Fender’s 6L6s) , with their greater power and gain, along with the ‘tight’ bass response afforded by the large speakers in the sealed boxes, that are most responsible for the ‘Marshall’ sound.

It is said that Pete Townsend was the impetus for the large human-height ‘stack’ aspect of the amplifier. The form of these things certainly suggests the huge volumes of sound/noise that they can produce. A great many bands used the ‘Marshall Stack’ in the 1970’s.

Nowadays, the ‘Marshall Stack’ is generally only used by true hard-rock and Metal bands, as well as the occasional ironic user. Well, maybe ironic. Who knows.

Nowadays, the ‘Marshall Stack’ is generally only used by true hard-rock and Metal bands, as well as the occasional ironic user. Well, maybe ironic. Who knows.

***********

*******

***

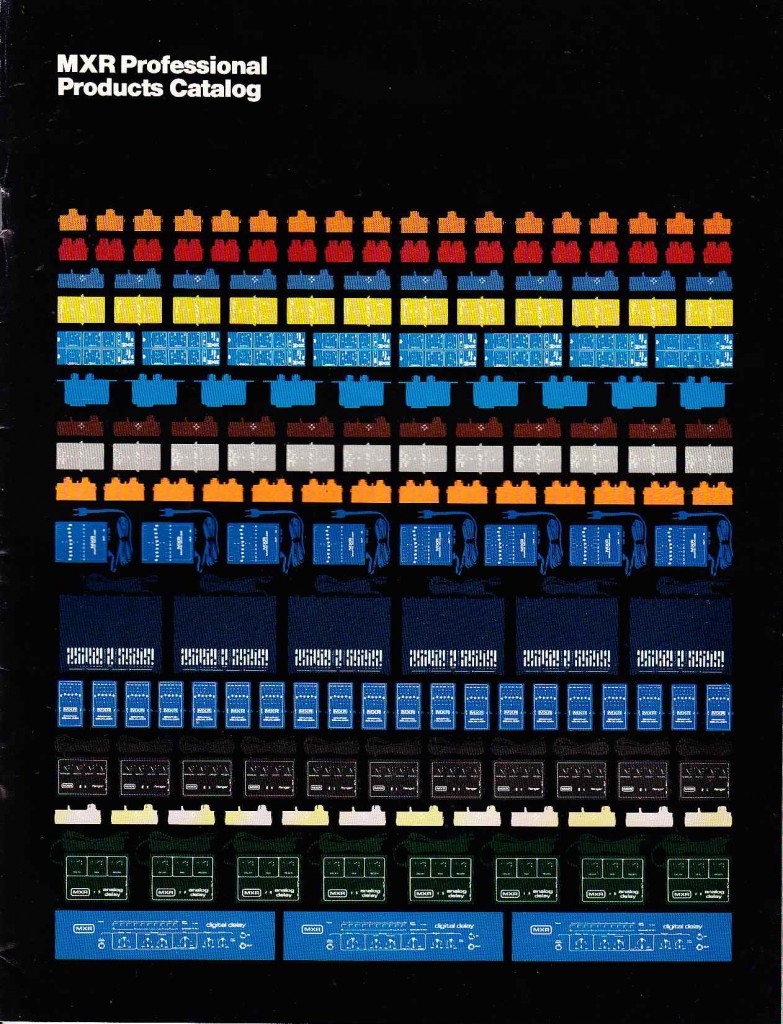

Today we will look at some early 70’s Marshall promotional material from the PS pile/archive.

Click on the link to download the entire 20-page 1971 full-line catalog: Marshall_1971_cat

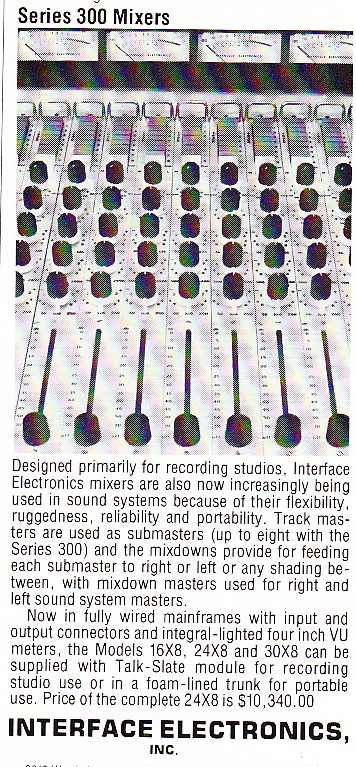

Some circa 1970 Marshall oddities. I have never come across any of these for sale anywhere. Anyone?

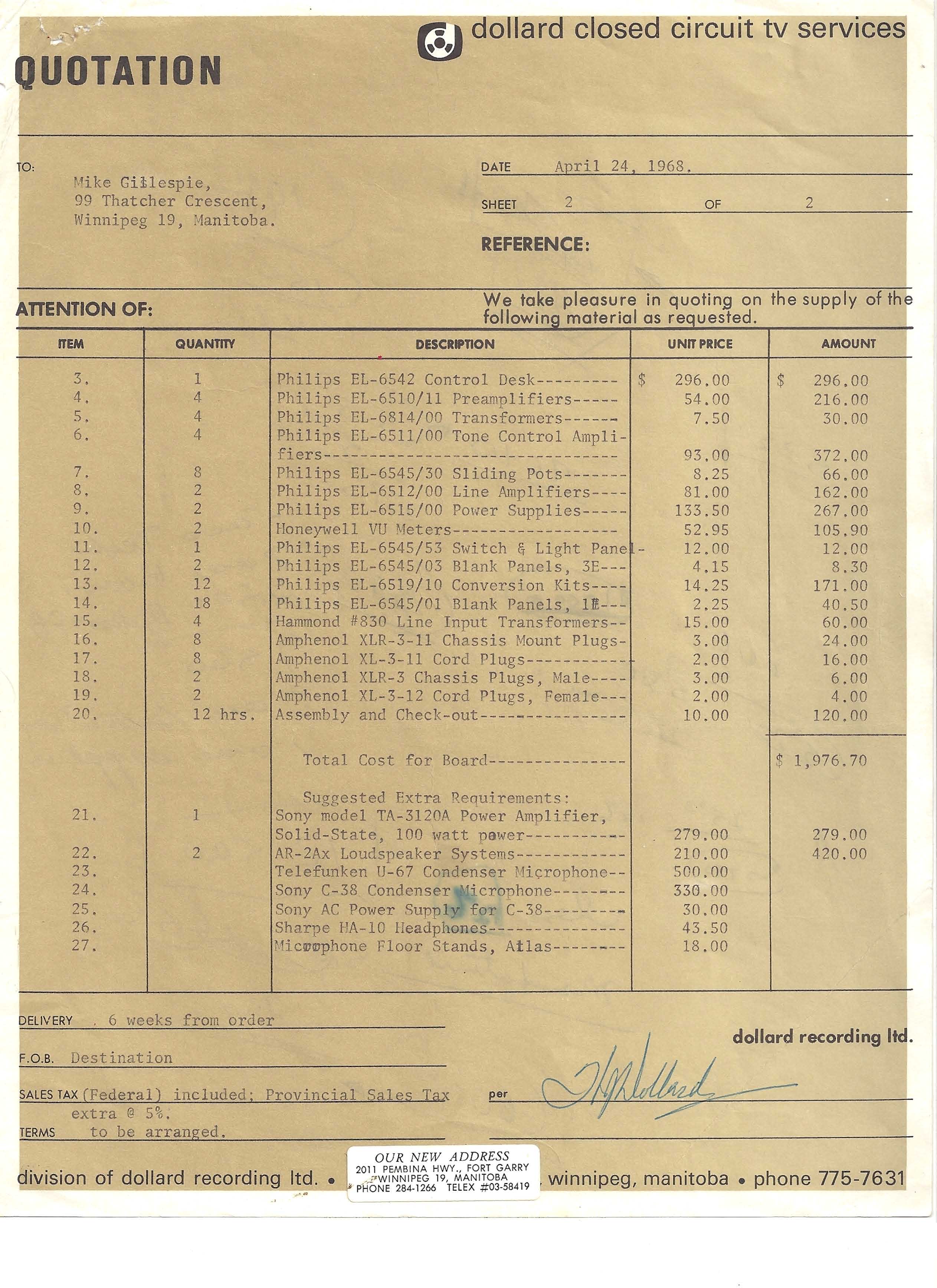

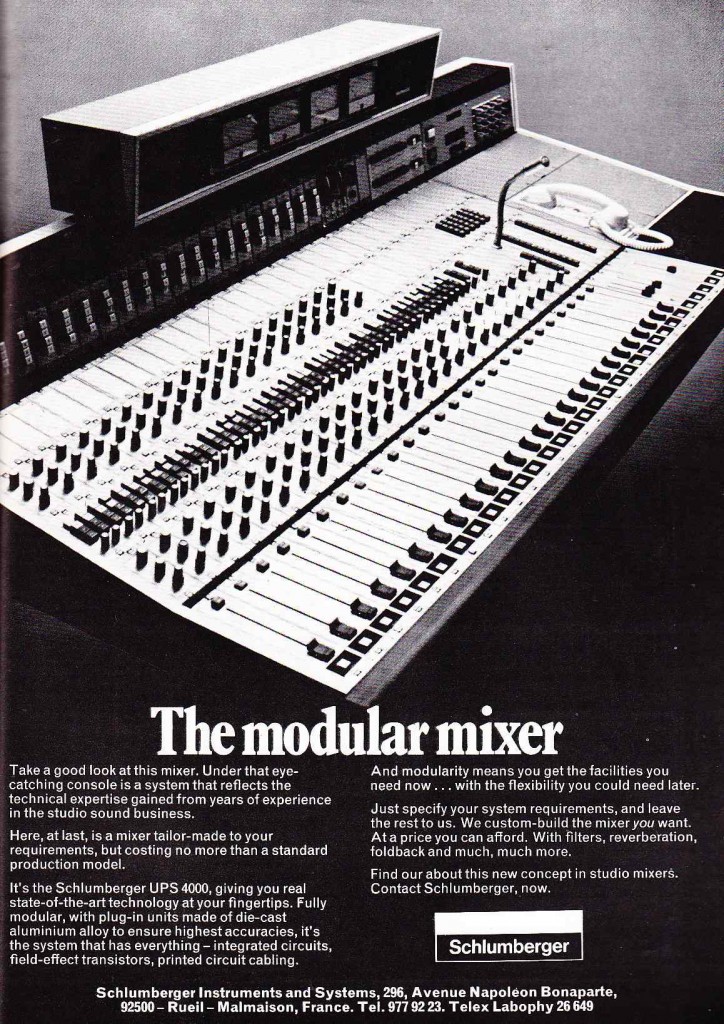

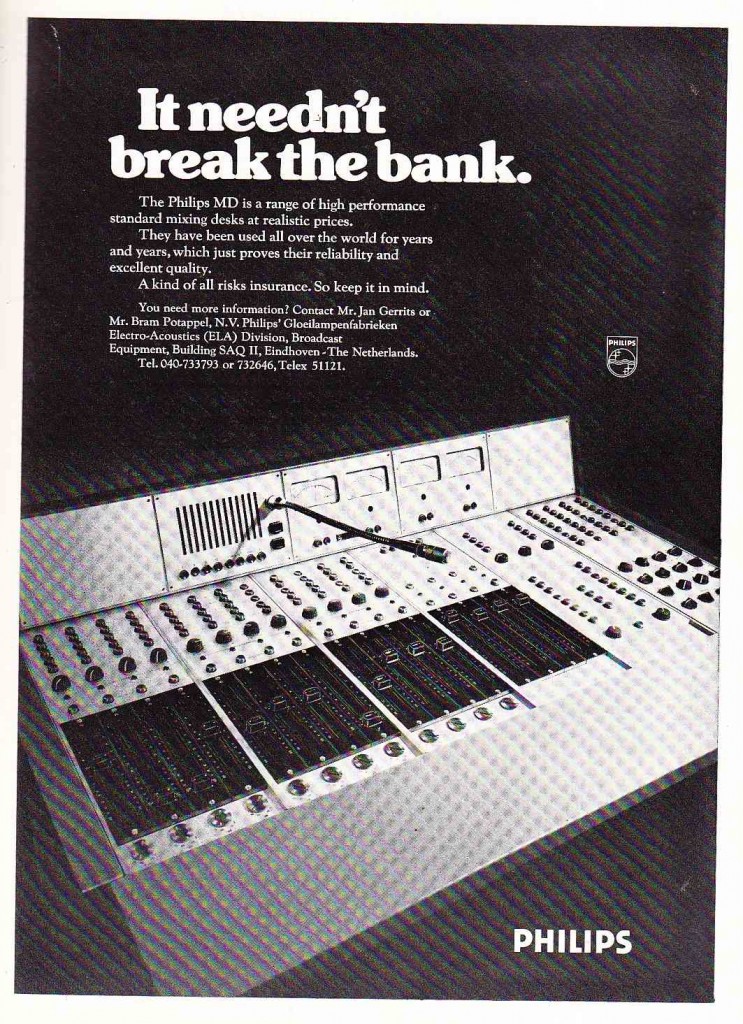

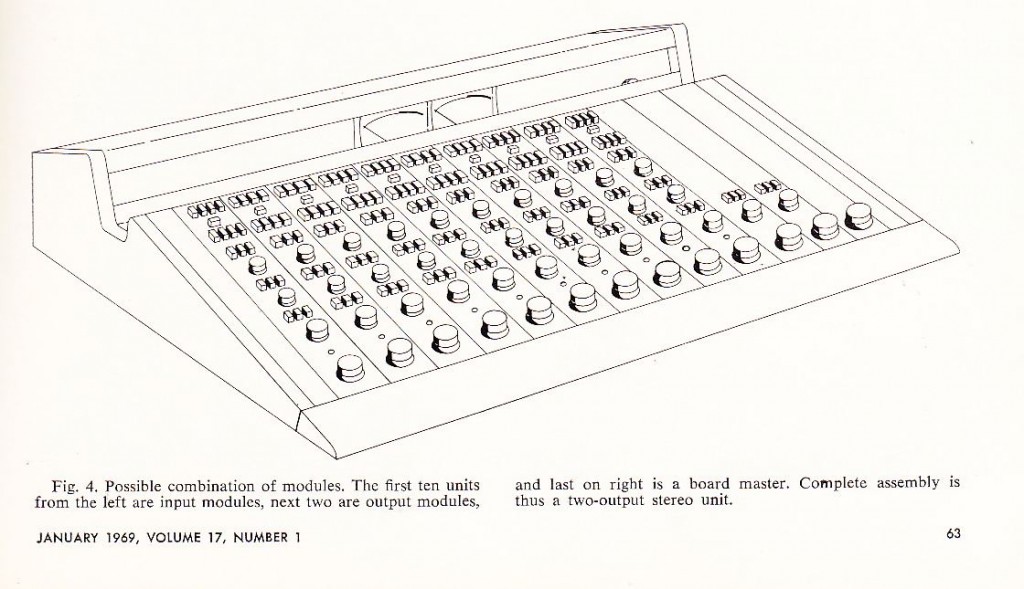

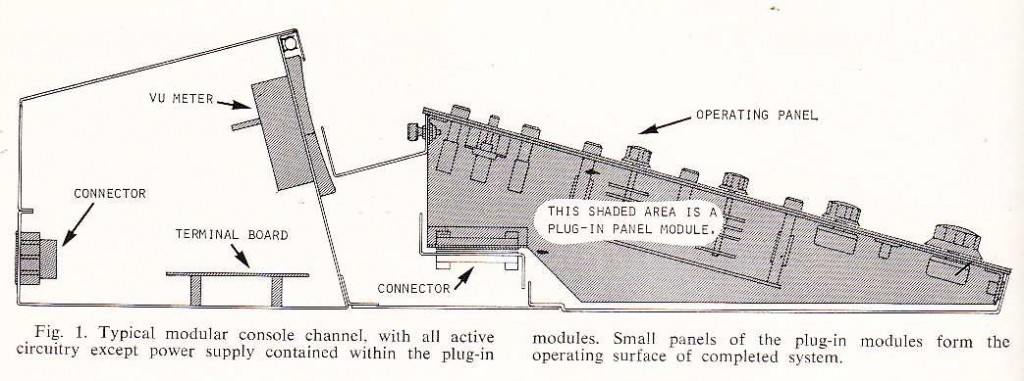

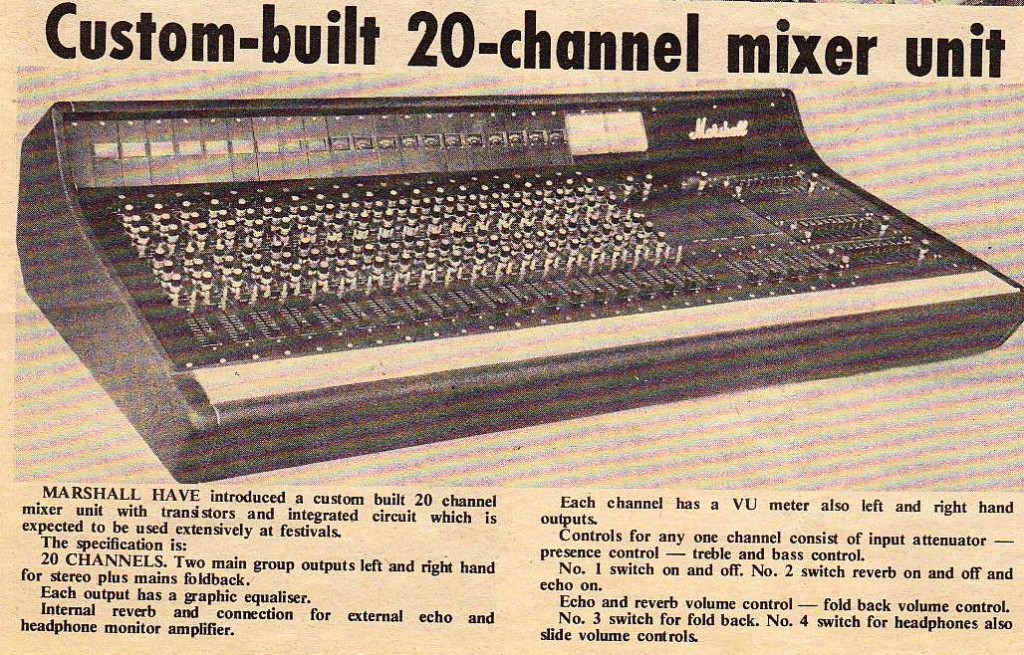

20-channel Marshall ‘festival’ mixer.

20-channel Marshall ‘festival’ mixer.

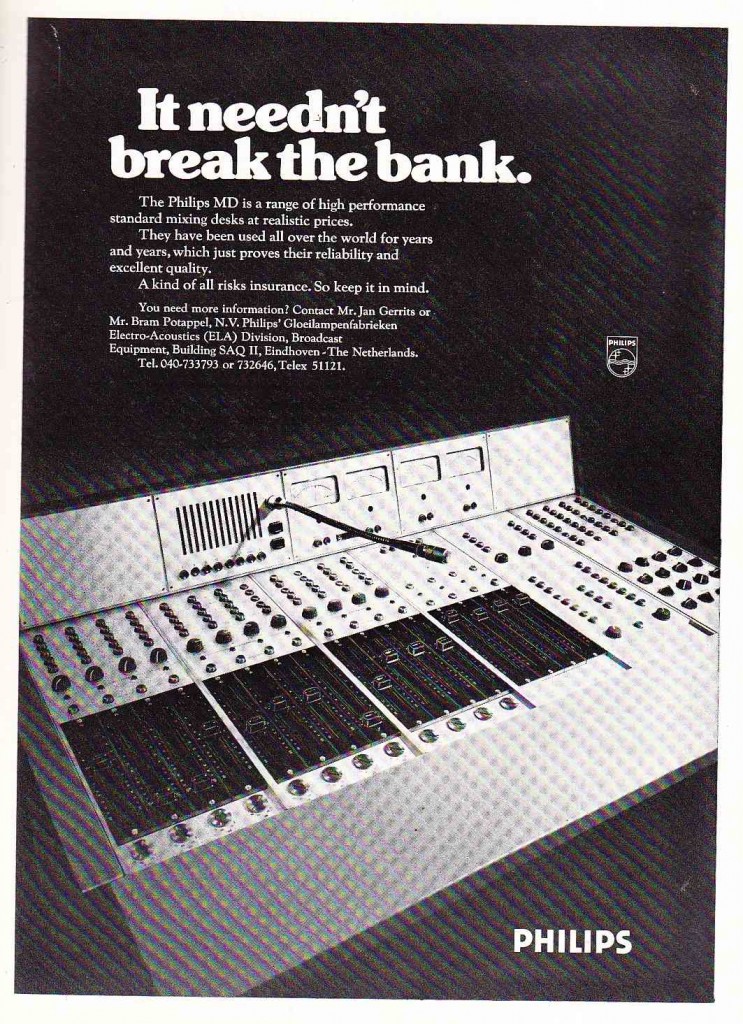

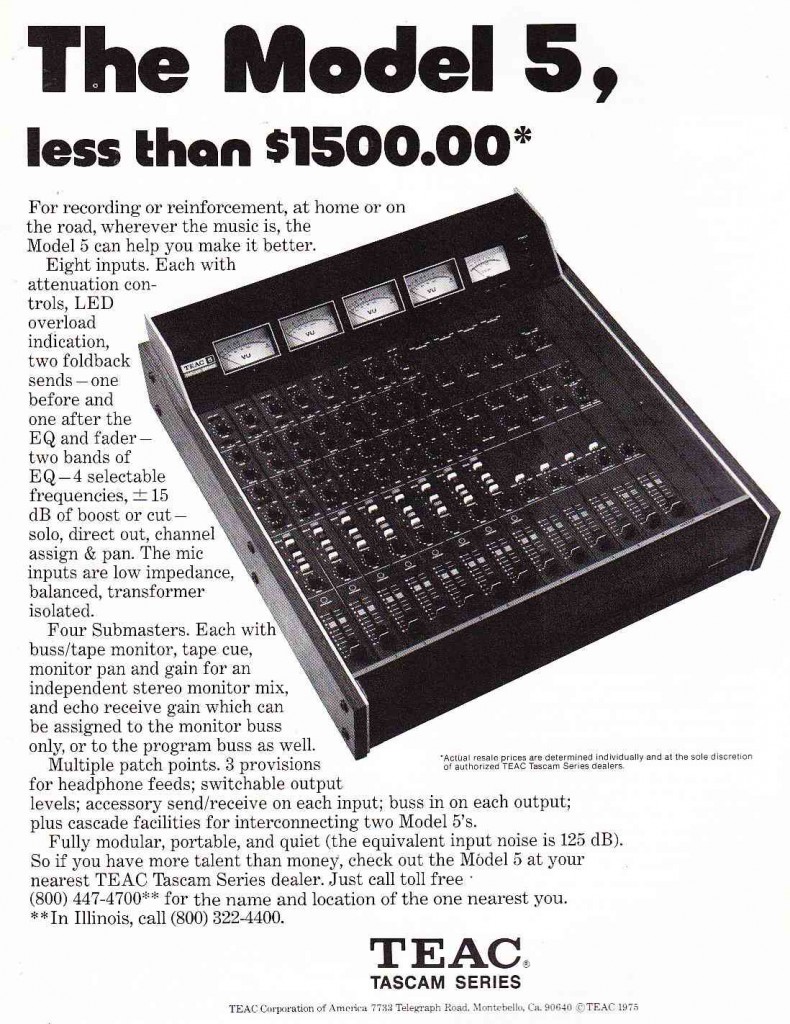

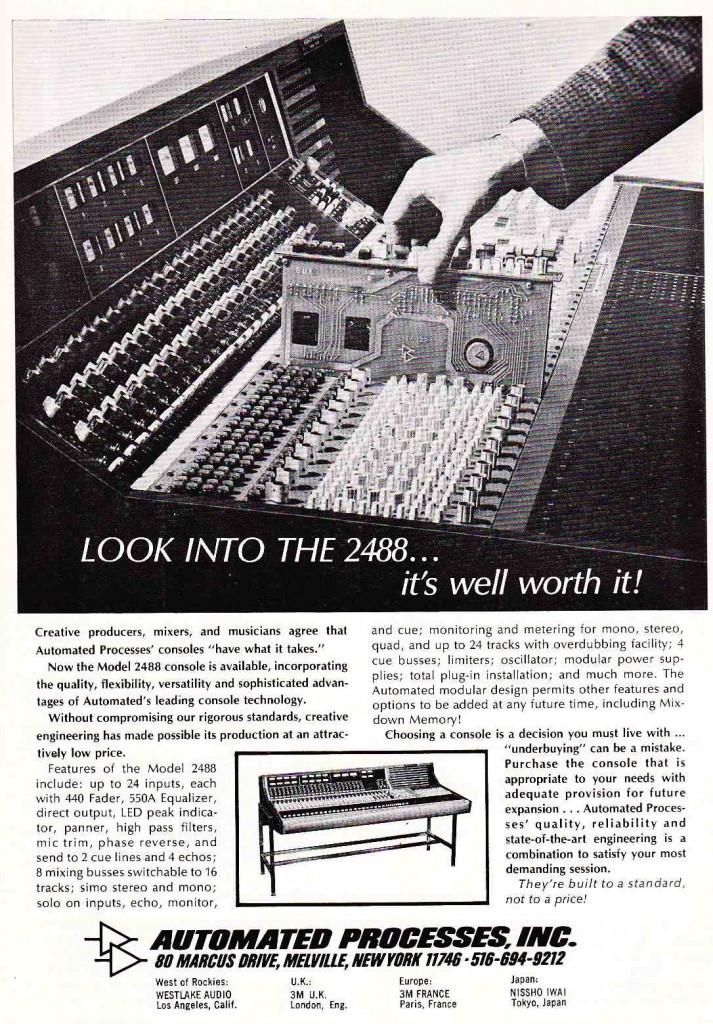

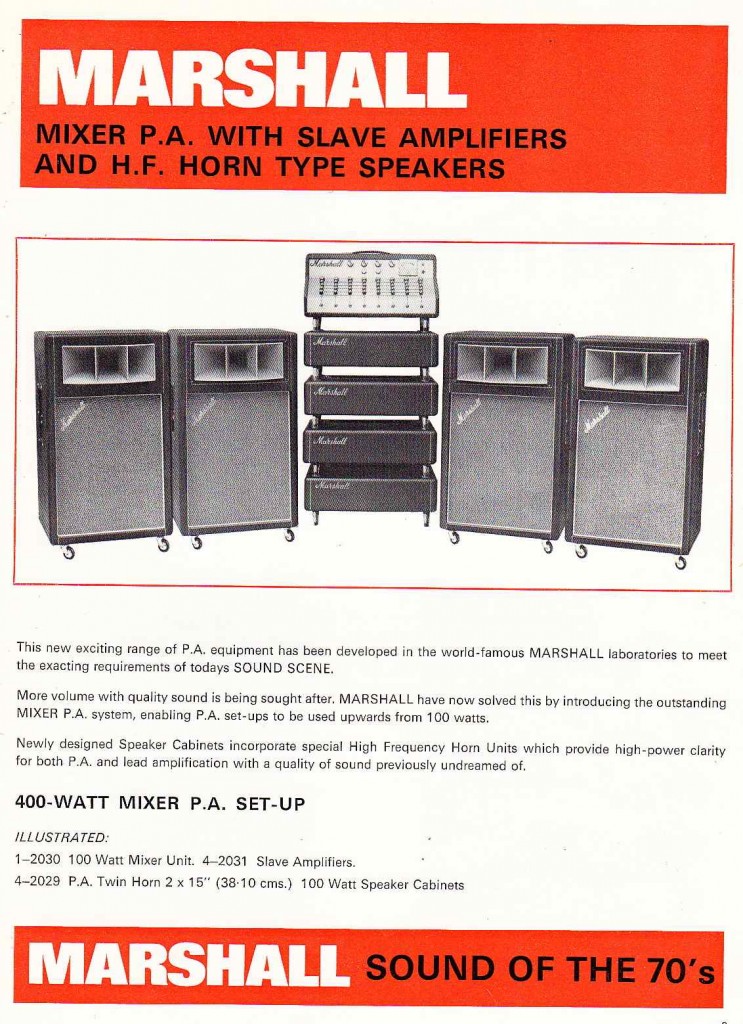

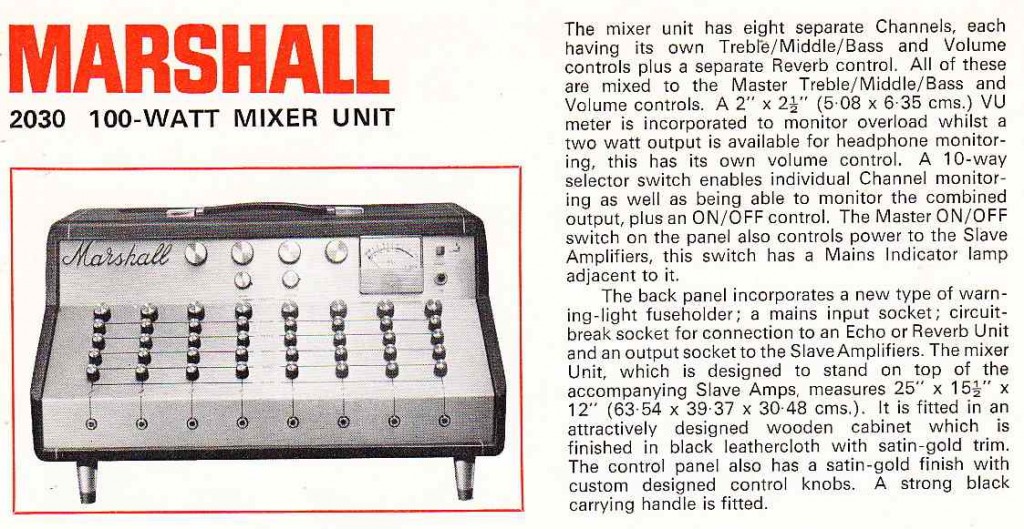

400-watt Marshall PA rig circa 1971. The Mixer unit actually had some pretty intelligent features for the day, like a 2-watt headphone amp with a simple single knob to cue any individual channel or the mix buss.

400-watt Marshall PA rig circa 1971. The Mixer unit actually had some pretty intelligent features for the day, like a 2-watt headphone amp with a simple single knob to cue any individual channel or the mix buss.

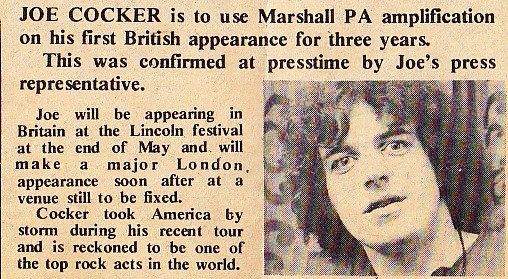

And who used this stuff? Joe Cocker, apparently.

And who used this stuff? Joe Cocker, apparently.

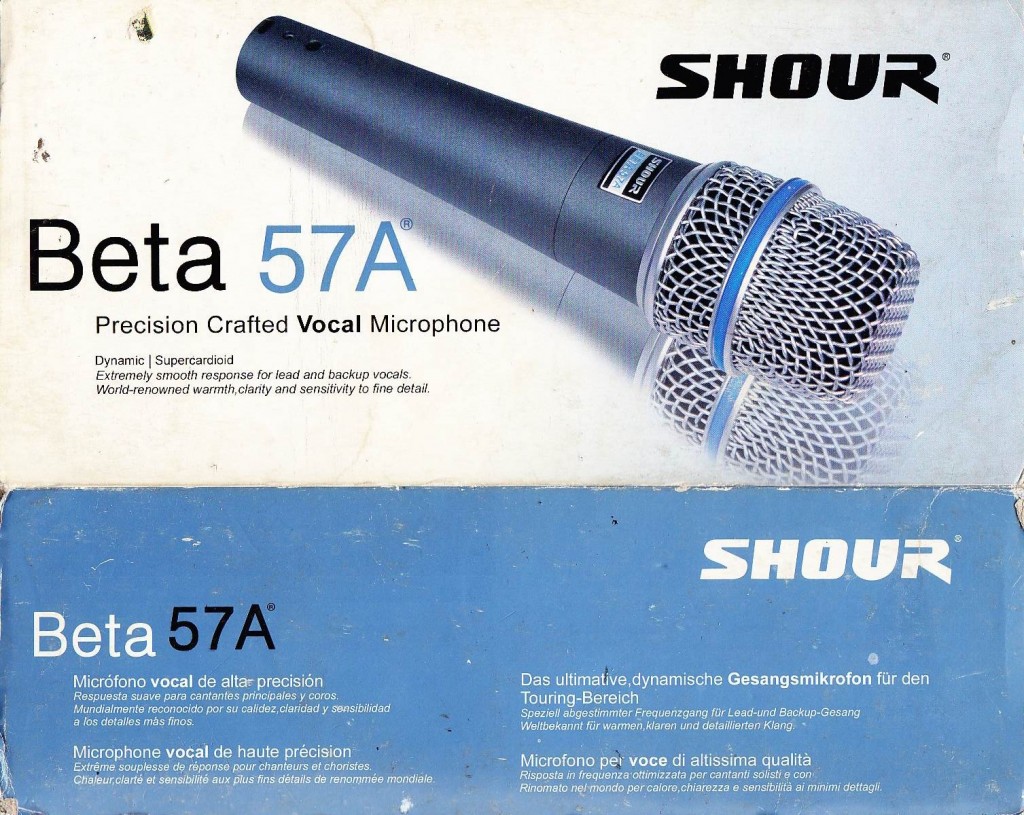

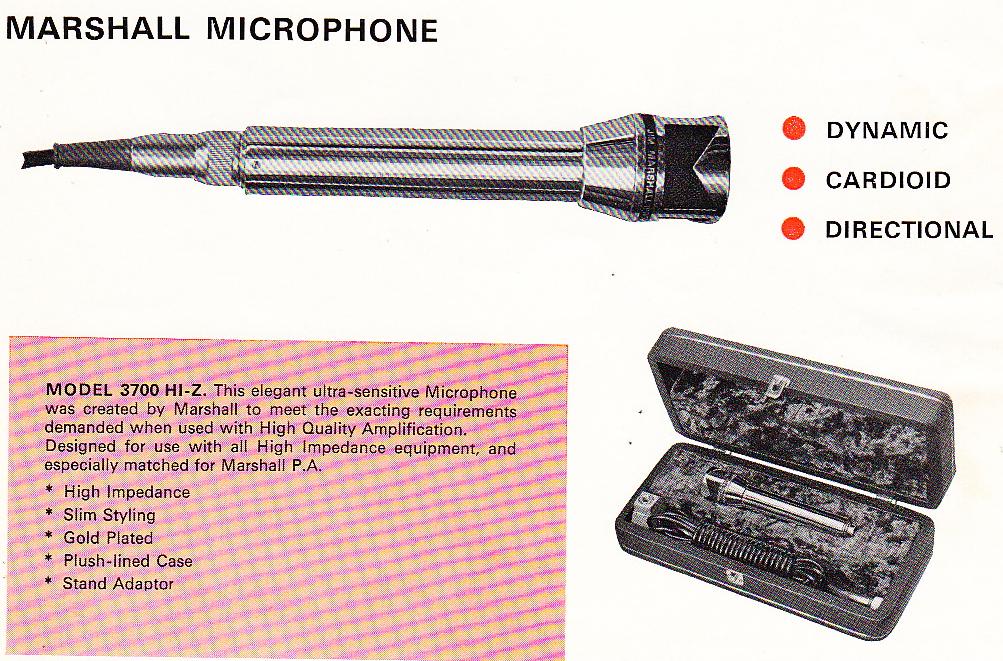

Marshall even marketed a Microphone at the time. The Model 3700. Looks shitty. It is nearly impossible to research this unit due to the fact that an entire line of Marshall (no relation) Mics is currently being made. Killer mic box, tho.

Marshall even marketed a Microphone at the time. The Model 3700. Looks shitty. It is nearly impossible to research this unit due to the fact that an entire line of Marshall (no relation) Mics is currently being made. Killer mic box, tho.

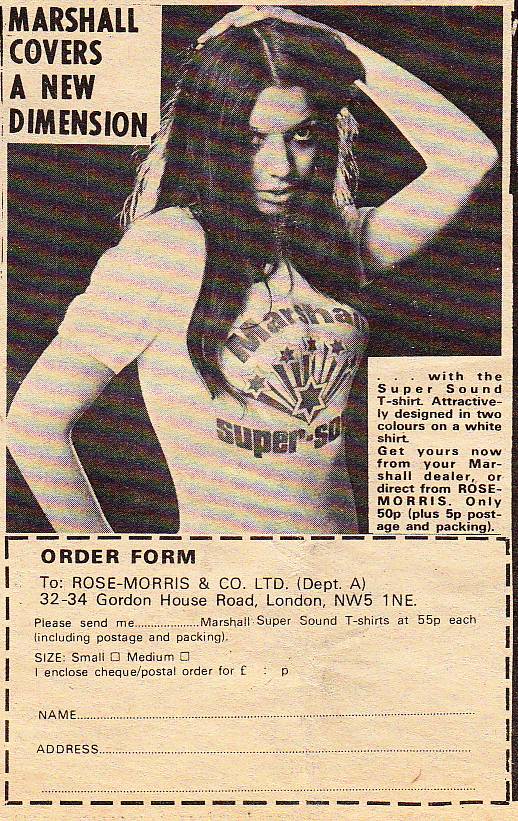

….And don’t forget the Marshal Super-Sound T-shirt. Wow. What can you say about this ad. Note that only small and medium are on offer.

….And don’t forget the Marshal Super-Sound T-shirt. Wow. What can you say about this ad. Note that only small and medium are on offer.

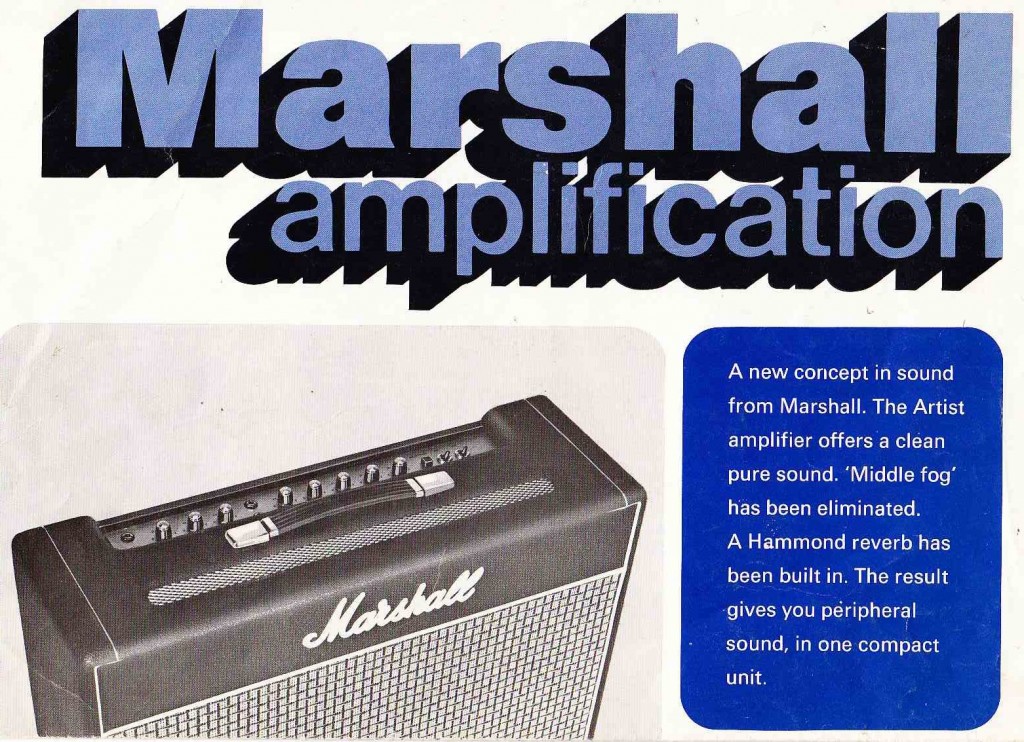

The Marshall Artist does turn up from time to time. I could get into one of these. Seems to be like a BluesBreaker plus reverb.

The Marshall Artist does turn up from time to time. I could get into one of these. Seems to be like a BluesBreaker plus reverb.

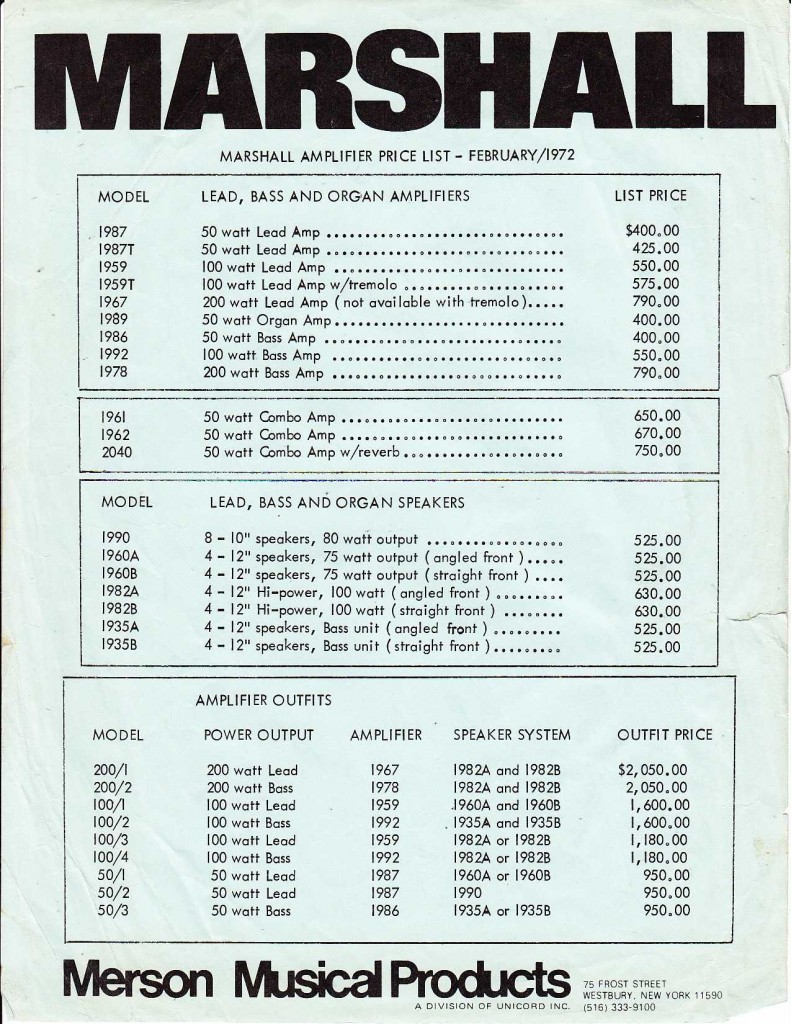

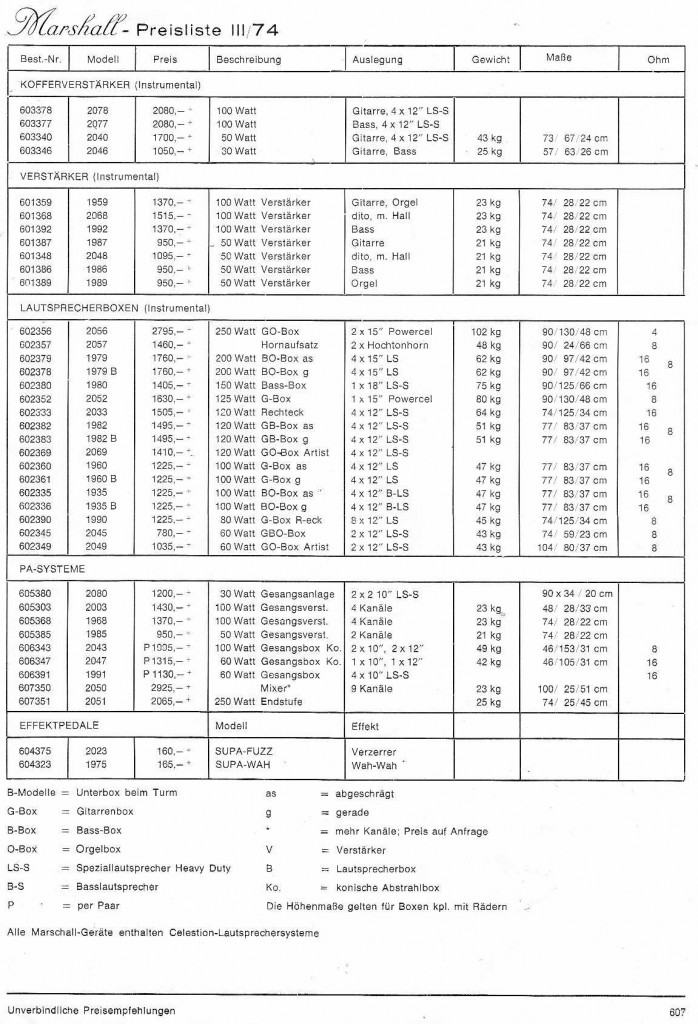

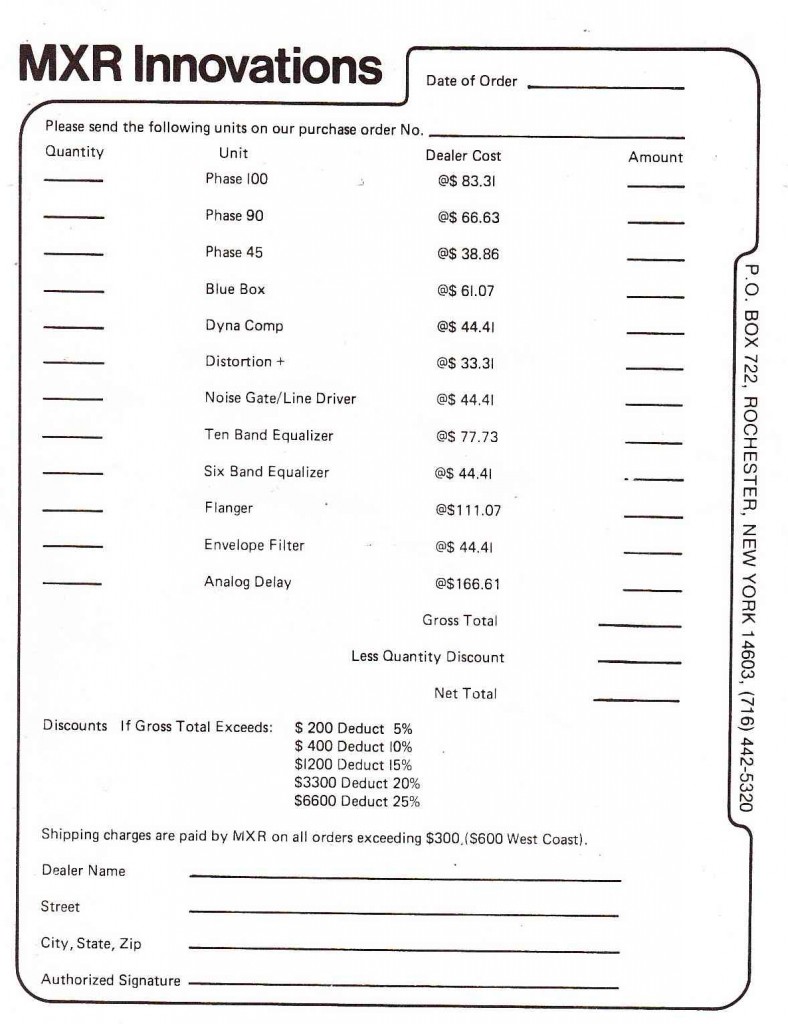

We’ll close this out with a couple of original pricelists: USA 1972 and Germany 1974. A reality check: the ‘stack’ of a 100-watt head plus 2 4×12 cabs was listed at $1600 in 1972. This equals $8629.69 in current US currency. Even allowing for usual 40% retail price deduction, that was still a $5000 amp. Good lord.