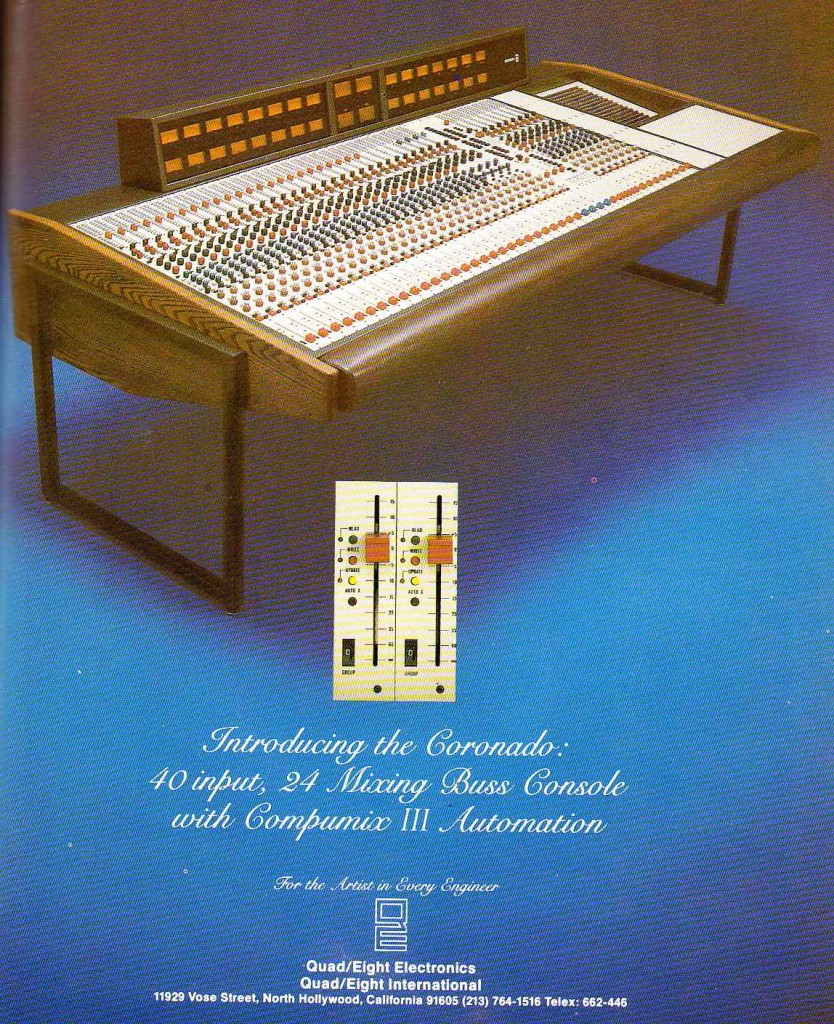

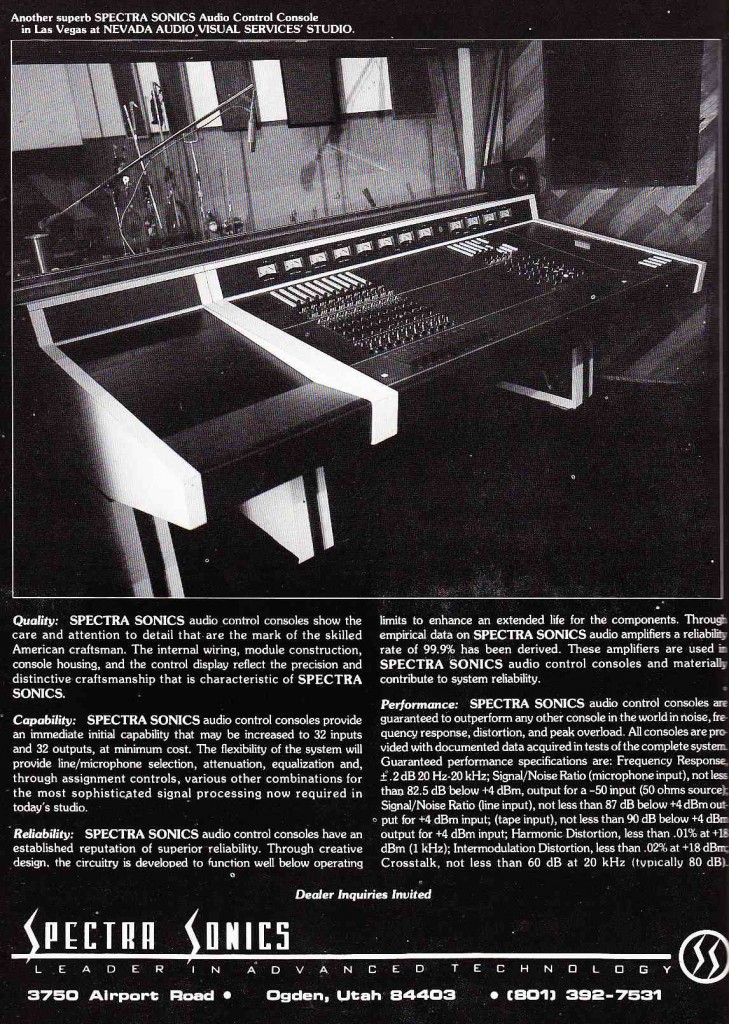

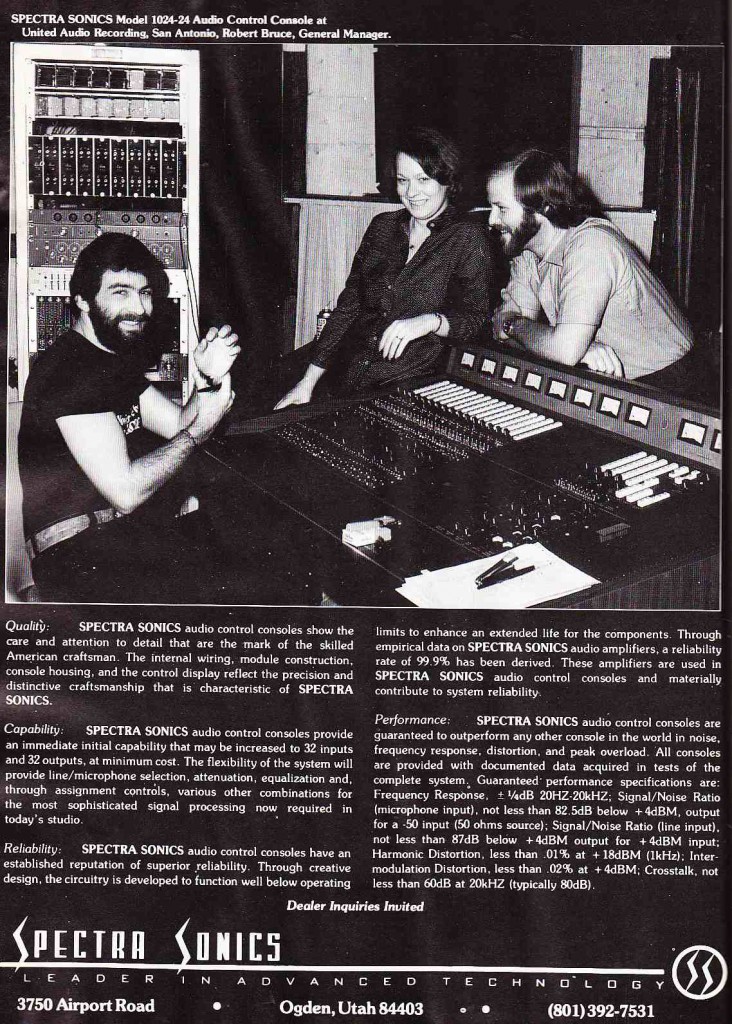

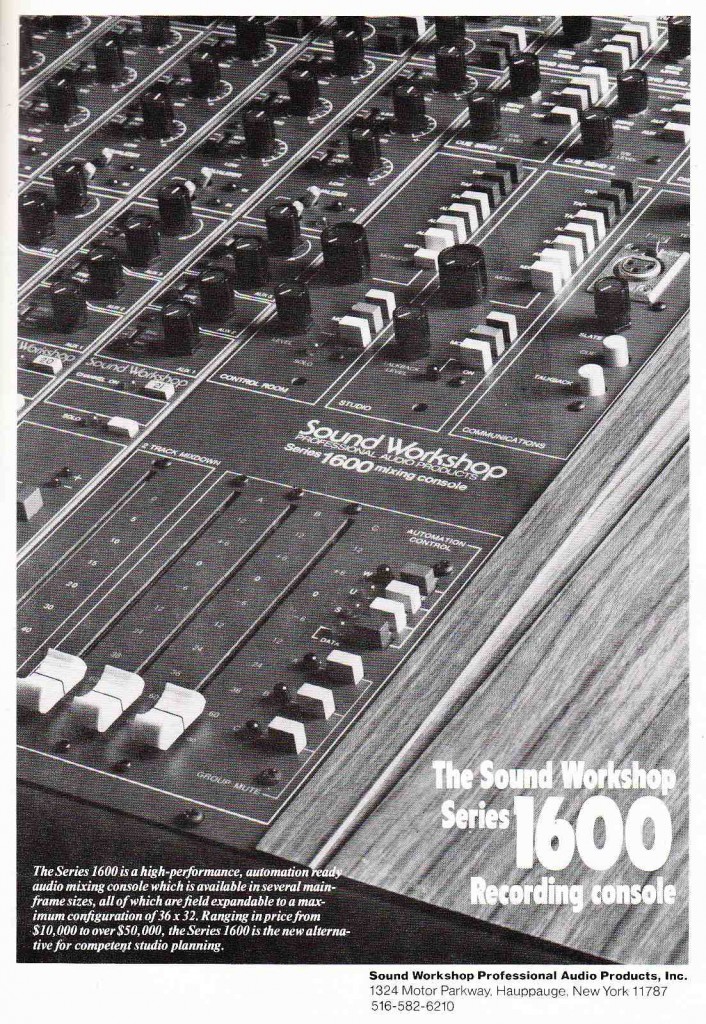

Following that review of SONY’s PCM-1, on a less technical note: some ‘eye-candy’ from 1978. New consoles from Quad/Eight, Harrison, Spectra-Sonics, and Sound Workshop.

Looking through a selection of Audio Engineering Society journals from 1978, we see several themes repeated. Primarily: digital signal processing (echo and primitive digital reverb) and digital recording. Papers dedicated to various issues concerning digital encoding and playback occupy many of these pages. Digital audio recording was a long way from being widely-accepted as professional practice in 1978, but based on the content of these publications, most in the field seem to have regarded it as inevitable. Most of the content of these issues is excruciating technical, and well beyond the scope of this website; one paper, though, brought light to a forgotten early chapter in the digital audio story.

Looking through a selection of Audio Engineering Society journals from 1978, we see several themes repeated. Primarily: digital signal processing (echo and primitive digital reverb) and digital recording. Papers dedicated to various issues concerning digital encoding and playback occupy many of these pages. Digital audio recording was a long way from being widely-accepted as professional practice in 1978, but based on the content of these publications, most in the field seem to have regarded it as inevitable. Most of the content of these issues is excruciating technical, and well beyond the scope of this website; one paper, though, brought light to a forgotten early chapter in the digital audio story.

***********

*******

***

When I first became involved with music recording in the early 1990s, I often heard vague stories of guys ‘recording digital audio onto VCRs.’ The September 1978 issue of the AES journal finally clarified this all for me. As it turns out, SONY was the first company to bring a digital-audio-recording product to mass-market.

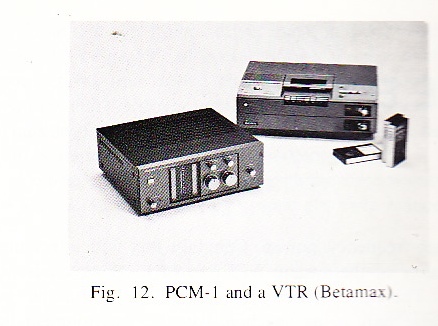

SONY’s PCM-1 (read an excellent period analysis here) was not a digital audio recorder, per se; rather, it was an early D/A and A/D converter which was used in conjunction with an analog video recorder as the data storage device.

Basically, the PCM-1 converted analog audio to a digital data stream, and then converted this digital stream into a video signal by adding video synchronization data to the digital audio stream. SONY’s engineers chose 44.05k / 16bit as their data spec. This is very close to our modern standard of 44.1 / 16 bit. Not sure why the slight difference. Anyone?

Basically, the PCM-1 converted analog audio to a digital data stream, and then converted this digital stream into a video signal by adding video synchronization data to the digital audio stream. SONY’s engineers chose 44.05k / 16bit as their data spec. This is very close to our modern standard of 44.1 / 16 bit. Not sure why the slight difference. Anyone?

Interesting stuff. A quick web search does not reveal any PCM-1s on the market; I wonder how many were sold in the US.

Interesting stuff. A quick web search does not reveal any PCM-1s on the market; I wonder how many were sold in the US.

Anyone use a PCM-1 or any of the later models? Any thoughts?

Is the digital audio signal from these SONY devices compatible with modern digital audio streams such as AES/EBU or spdif?

From the back-pages of the AES Journal in 1965:

Moog is a legendary name in the world of music. As far as manufacturers/innovators of musical/audio equipment go, Robert Moog is a close to a household name as anyone I can think of. The original Moog Modular Synthesizer, as used in early ‘hit’ electronic records such as Carlos’ “Switched on Bach,” was the earliest commercially-available integrated audio synthesizer instrument.

Moog is a legendary name in the world of music. As far as manufacturers/innovators of musical/audio equipment go, Robert Moog is a close to a household name as anyone I can think of. The original Moog Modular Synthesizer, as used in early ‘hit’ electronic records such as Carlos’ “Switched on Bach,” was the earliest commercially-available integrated audio synthesizer instrument.

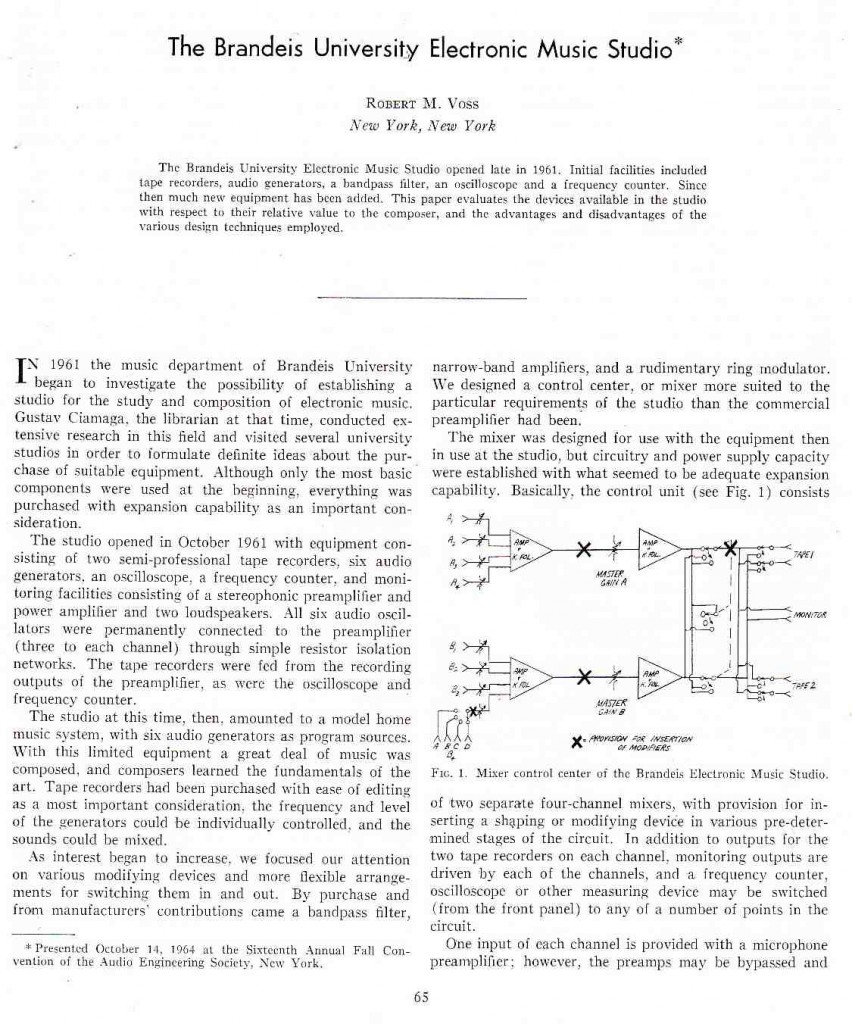

But as much as Moog was indeed an innovator and a massive contributor to the world of music and audio, widespread acceptance of his (and others – Buchla, EMS, etc) synthesizer systems actually marked the demise of a much earlier tradition of electronic music practice. Because the Moog Modular, complex and inscrutable as it now seems, was in fact a massive simplification and streamlining of the earlier academic/institutional ad-hoc electronic music studio. Today we will start (what I intend to be) a series of investigations into the technology of early studios used by electronic pioneers such as Varese, Stockhausen, and Luening.

I am slowly-but-surely accumulating some of the original circa 1960 equipment similar to that which pre-Moog electronic music was created with, and I hope to attempt some of this early practice myself.

***********

*******

***

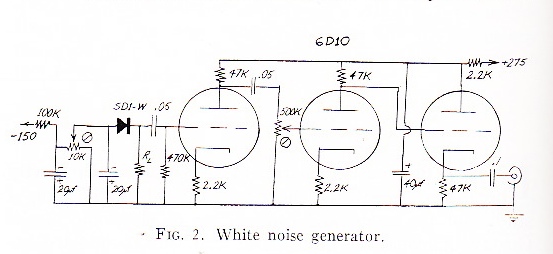

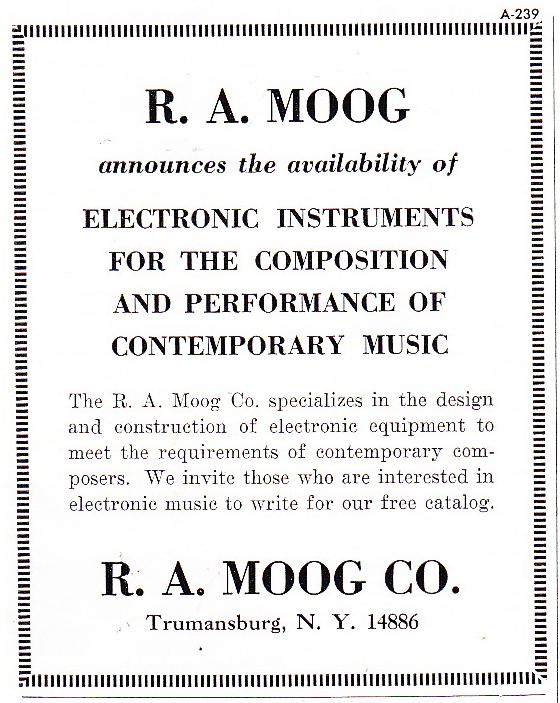

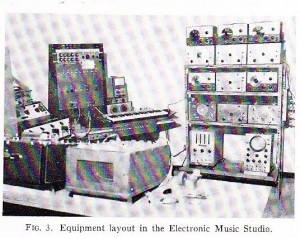

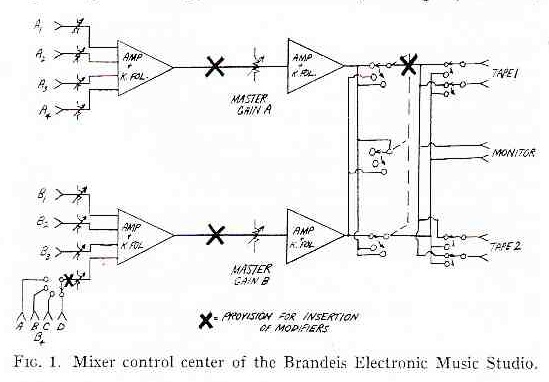

This article, from the same 1965 issue of the AES journal which heralded the arrival of ‘The Moog,” details a basic ad-hoc electronic studio of the era. Read through it. The basic components that Robert Moog integrated into his ‘modular instrument’ are all present in the Brandeis studio, minus the keyboard: oscillators, a mixer, a filter, a noise generator, a ring modulator, a spring reverb unit. And, of course, several tape-recorders to allow the various sounds to be layered and combined in order to meet the composer’s intent. In order to understand just how much effort was necessary to create even these basic conditions for composing, consider this: the (very simple) mixer had to be custom-designed and built by an engineering firm.

This article, from the same 1965 issue of the AES journal which heralded the arrival of ‘The Moog,” details a basic ad-hoc electronic studio of the era. Read through it. The basic components that Robert Moog integrated into his ‘modular instrument’ are all present in the Brandeis studio, minus the keyboard: oscillators, a mixer, a filter, a noise generator, a ring modulator, a spring reverb unit. And, of course, several tape-recorders to allow the various sounds to be layered and combined in order to meet the composer’s intent. In order to understand just how much effort was necessary to create even these basic conditions for composing, consider this: the (very simple) mixer had to be custom-designed and built by an engineering firm.

And the studio-staff themselves designed and built the white-noise generator that the set-up used.

And the studio-staff themselves designed and built the white-noise generator that the set-up used.

*******

***

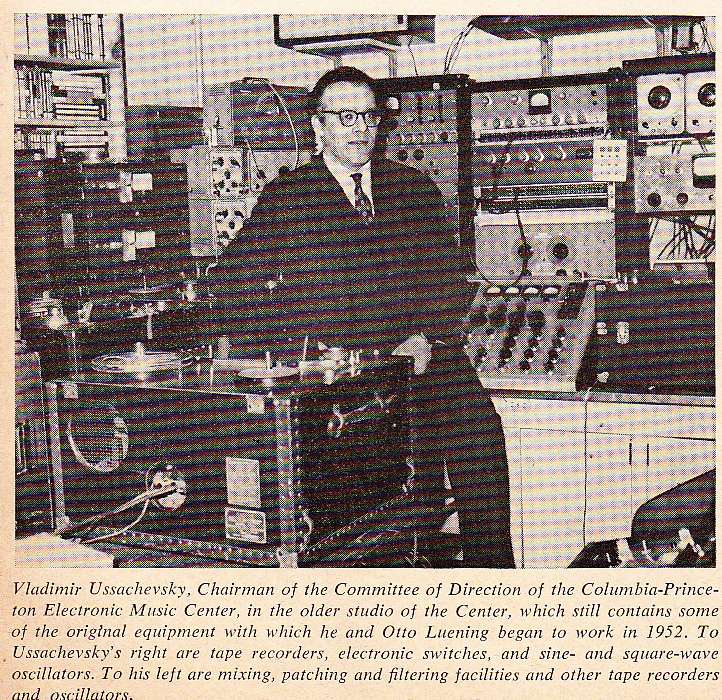

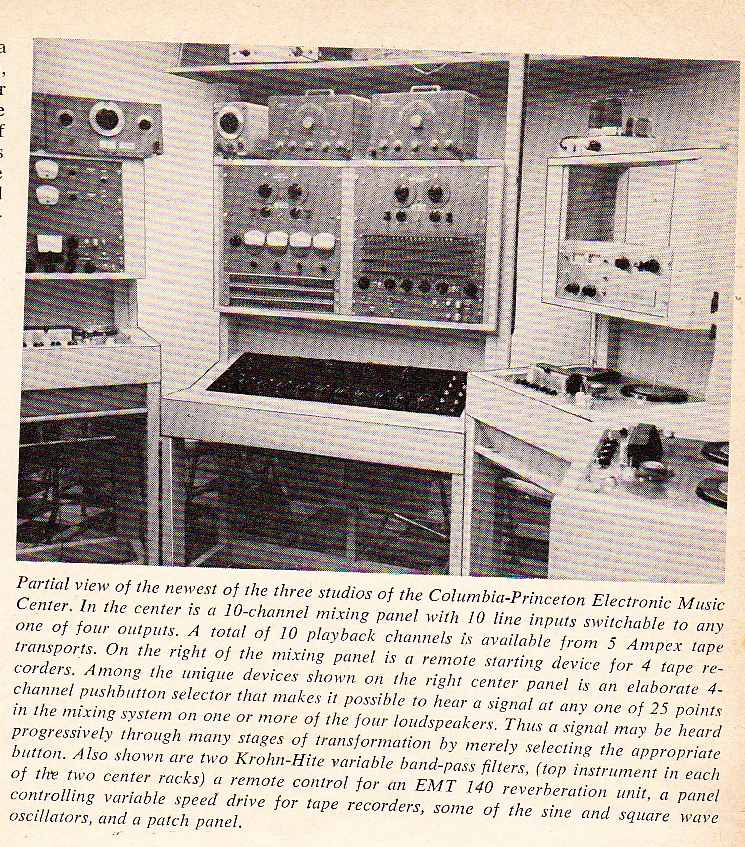

Columbia University had a similar, but much more sophisticated studio at the time. They began the construction of their set-up in 1952, nine years before Brandeis did the same.

Here the Columbia/Princeton studio is profiled in the June 1965 issue of ‘Radio Electronics,’ the same year that the AES covered Brandeis.

You can here some of the music that Otto Luening made on this rig (presumably) at the youtube link earlier in my article. I find it to be very beautiful; it is in many ways the most basic type of music: I think we experience it directly as ‘Organized Noise,’ as free-as-possible from cliche and expectation. Just my $.02.

You can here some of the music that Otto Luening made on this rig (presumably) at the youtube link earlier in my article. I find it to be very beautiful; it is in many ways the most basic type of music: I think we experience it directly as ‘Organized Noise,’ as free-as-possible from cliche and expectation. Just my $.02.

***********

*******

***

As I had mentioned earlier, Moog’s real innovation was to take all of the disparate components of electronic sound-generation – the oscillators, mixer, filters, noise generator, ring modulator, a spring reverb – and combine them into little panels that fit a single chassis, with a conventional piano-type keyboard as the primary input-control device.

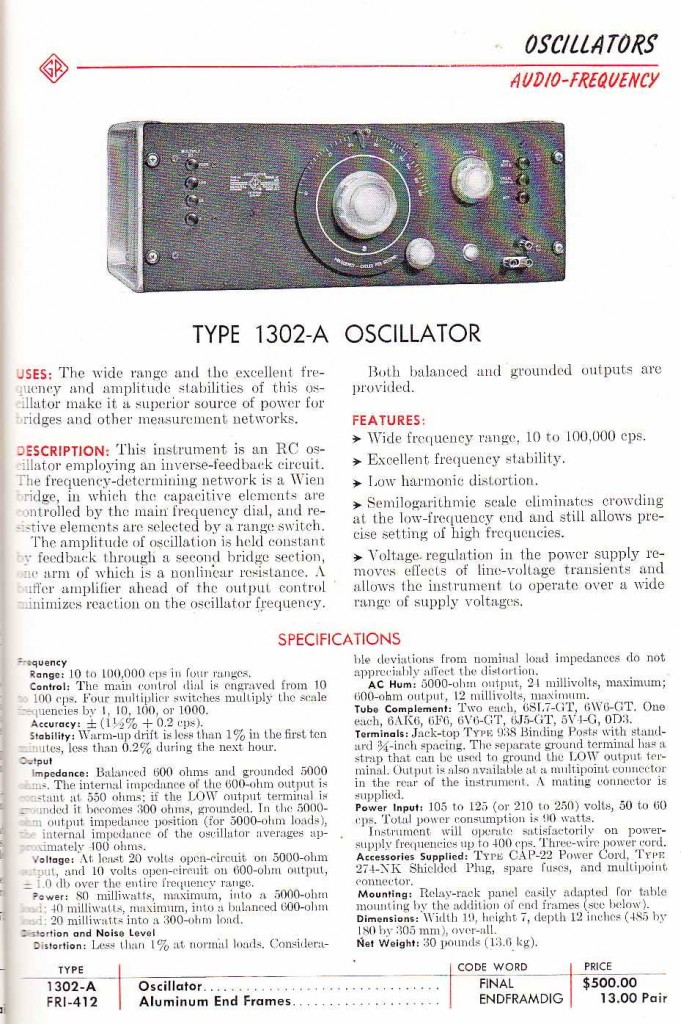

But where did our pre-Moog pioneers source their hardware? As the c. 1965 coverage indicates, Brandeis and Columbia had some of it custom built; some was built by the staff; and some originated as non-musical laboratory equipment.

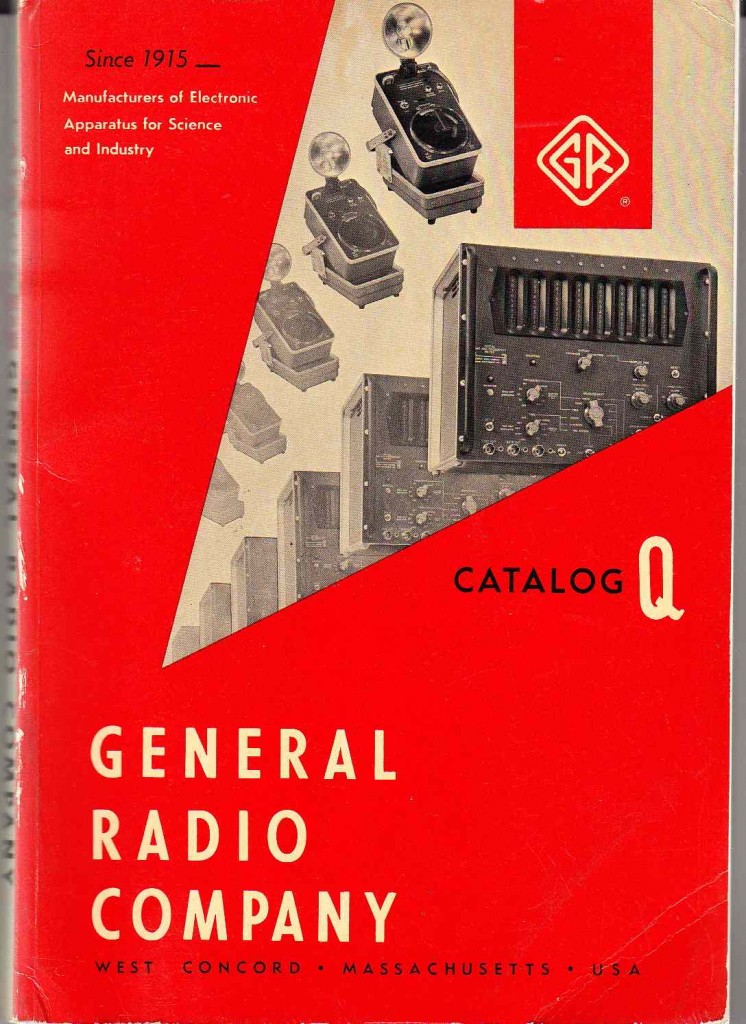

General Radio was perhaps the pre-eminent manufacturer of electronic test equipment in the 1950s and 1960s. I have owned some of their pieces, and the build-quality is absolutely incredible.

General Radio was perhaps the pre-eminent manufacturer of electronic test equipment in the 1950s and 1960s. I have owned some of their pieces, and the build-quality is absolutely incredible.

This type of hardware is fairly easily obtained nowadways for very little money – i generally pay $5 – $20 for a unit – and usually it still works. Sometimes it is hard to resist the temptation to chop up these pieces in order to use the valuable transformers for other projects, but I have saved a few of the better pieces in the hopes of getting my own super-primitive Electronic Composing Studio together.

*******

***

Anyone out there ever made music on a pre-Moog system?

Anyone attend the Brandeis or Columbia programs in the early 1960’s? Drop a line and let know about it.

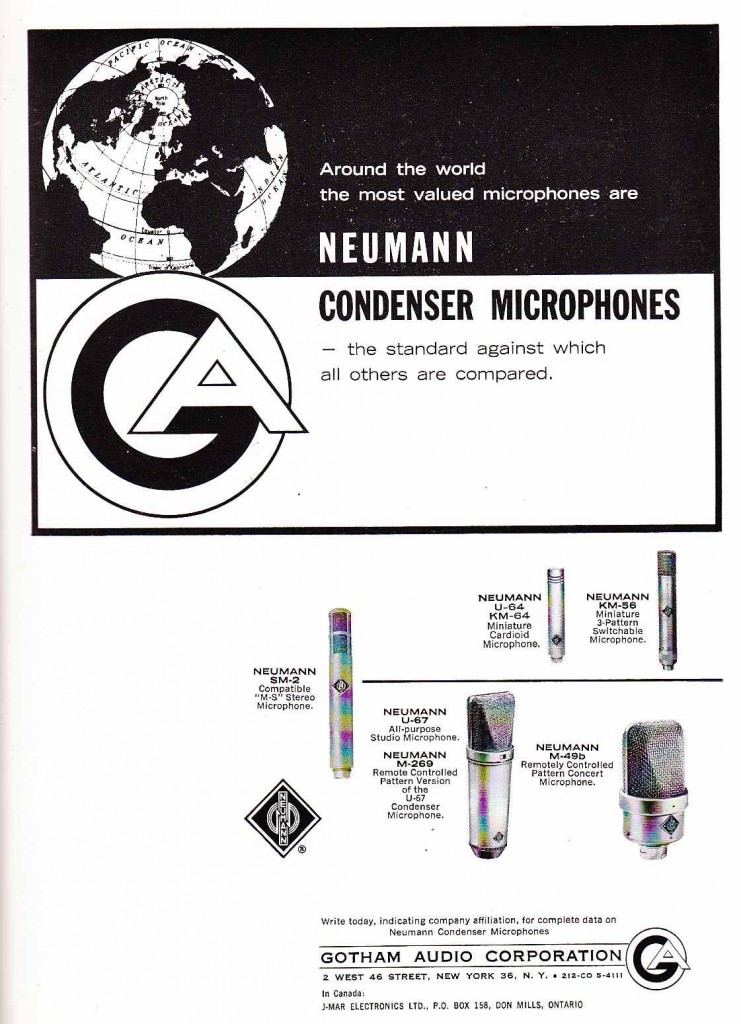

Courtesy of the Audio Engineering Society’s 1965 Membership Directory Publication: today we take a look at some ‘full-product-line’ advertising from the the leading microphone-makers of 1965. Shure, Beyer, and RCA are curiously absent.

Gotham Audio of NYC was the sole USA importer/distributor of Neumann Mics for a very long time. It is incredible to me how Neumann’s reputation has stayed so strong for so many years. Sort of like… Mercedes? BMW? Maybe there is something to be said for quality vs. price-point-engineering after all.

Gotham Audio of NYC was the sole USA importer/distributor of Neumann Mics for a very long time. It is incredible to me how Neumann’s reputation has stayed so strong for so many years. Sort of like… Mercedes? BMW? Maybe there is something to be said for quality vs. price-point-engineering after all.

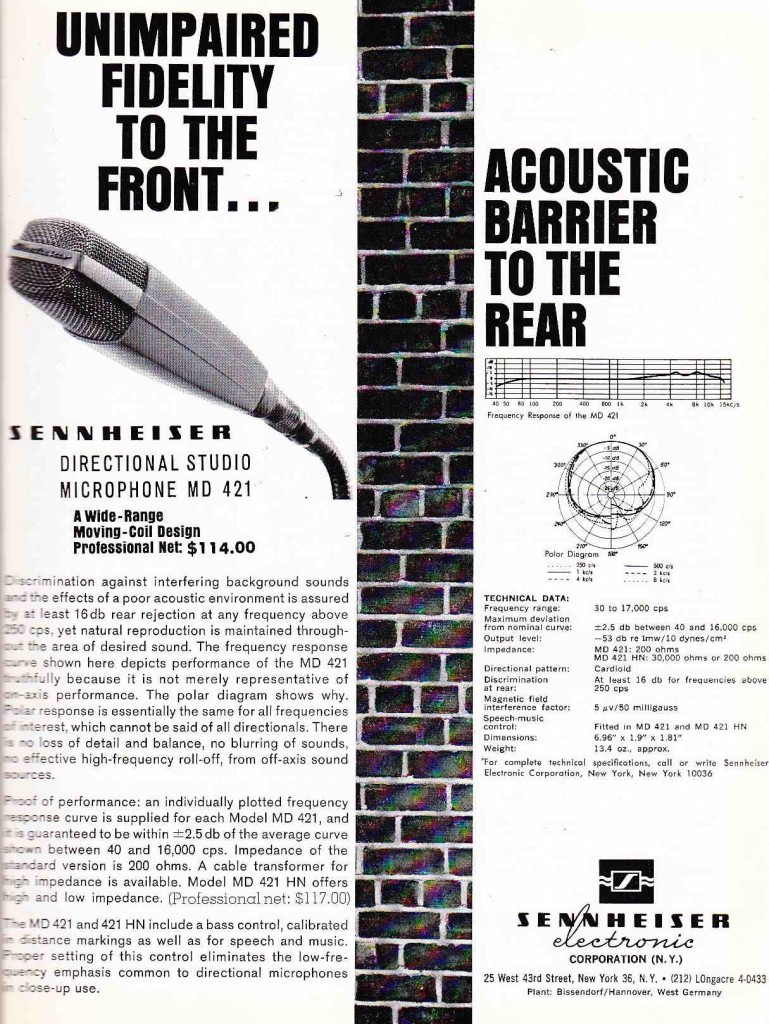

I knew that 421s were popular in the 1960s, but i had not realized that they were available as early as 1965! This is an incredible product. The 421 is still considered a world-class mic choice for tom drums, as well as bass guitar and kick drum for certain sounds. I have also found it a great mic for aggressive rock vocals. FORTY FIVE YEARS and these things are still in demand.

I knew that 421s were popular in the 1960s, but i had not realized that they were available as early as 1965! This is an incredible product. The 421 is still considered a world-class mic choice for tom drums, as well as bass guitar and kick drum for certain sounds. I have also found it a great mic for aggressive rock vocals. FORTY FIVE YEARS and these things are still in demand.

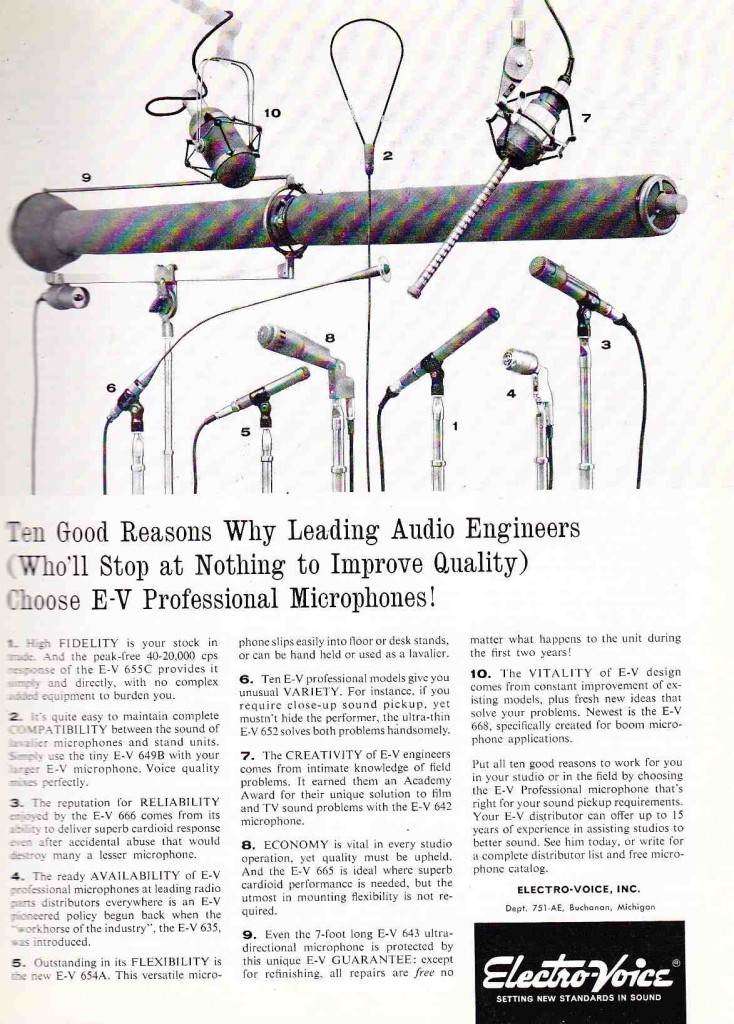

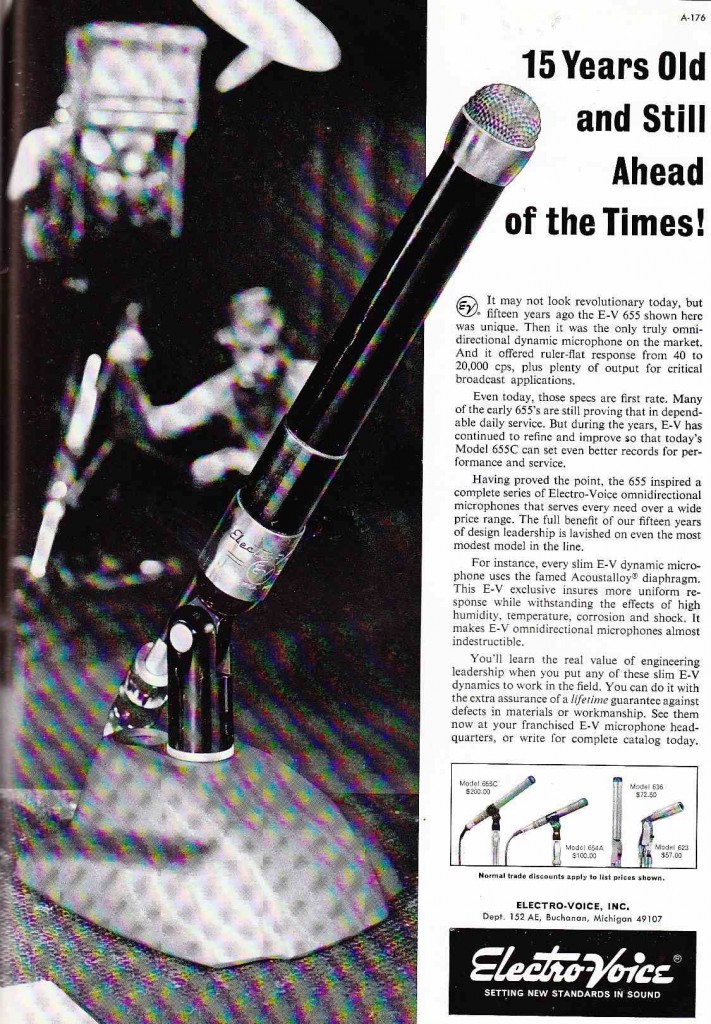

Ah yes the EV line. Need to do that 655 listening test! Also this reminds me that I need to find a model 666. Satan references aside, the 666 is somewhat the predecessor to the EV RE-20, which is to this day one of my all-time favorite microphones. Gets used on every session.

Ah yes the EV line. Need to do that 655 listening test! Also this reminds me that I need to find a model 666. Satan references aside, the 666 is somewhat the predecessor to the EV RE-20, which is to this day one of my all-time favorite microphones. Gets used on every session.

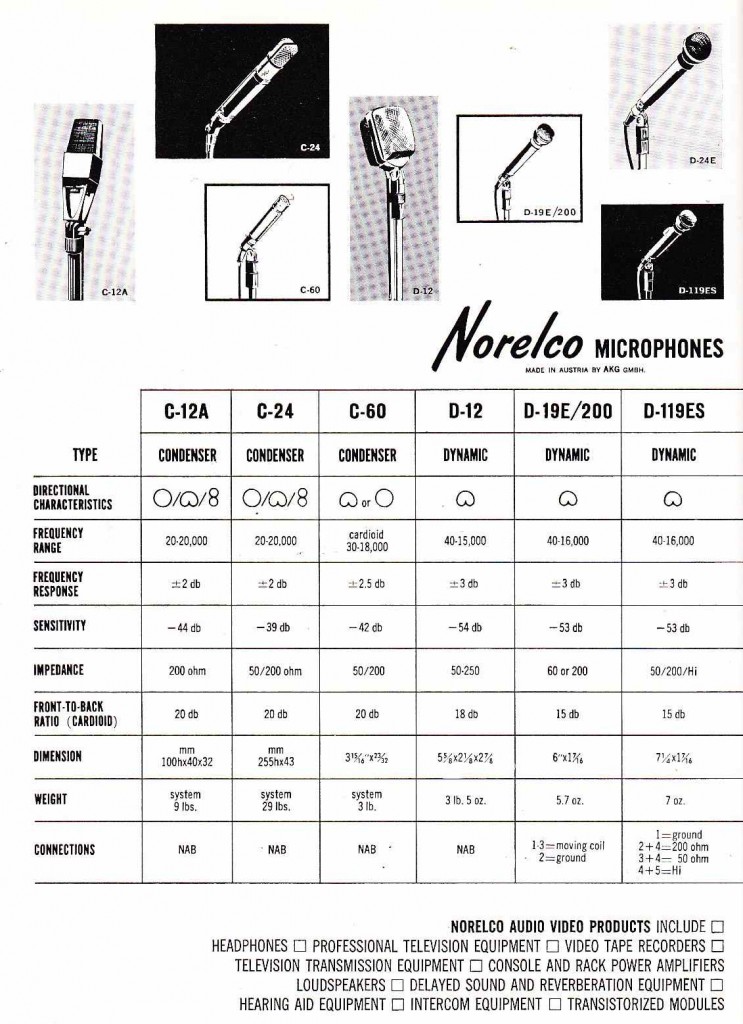

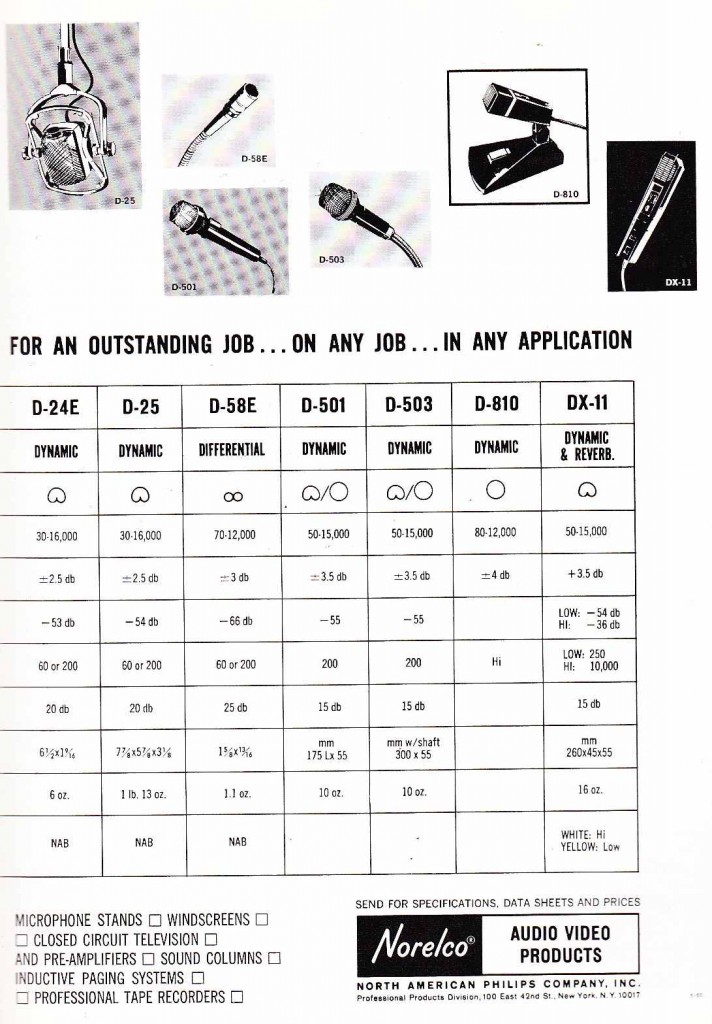

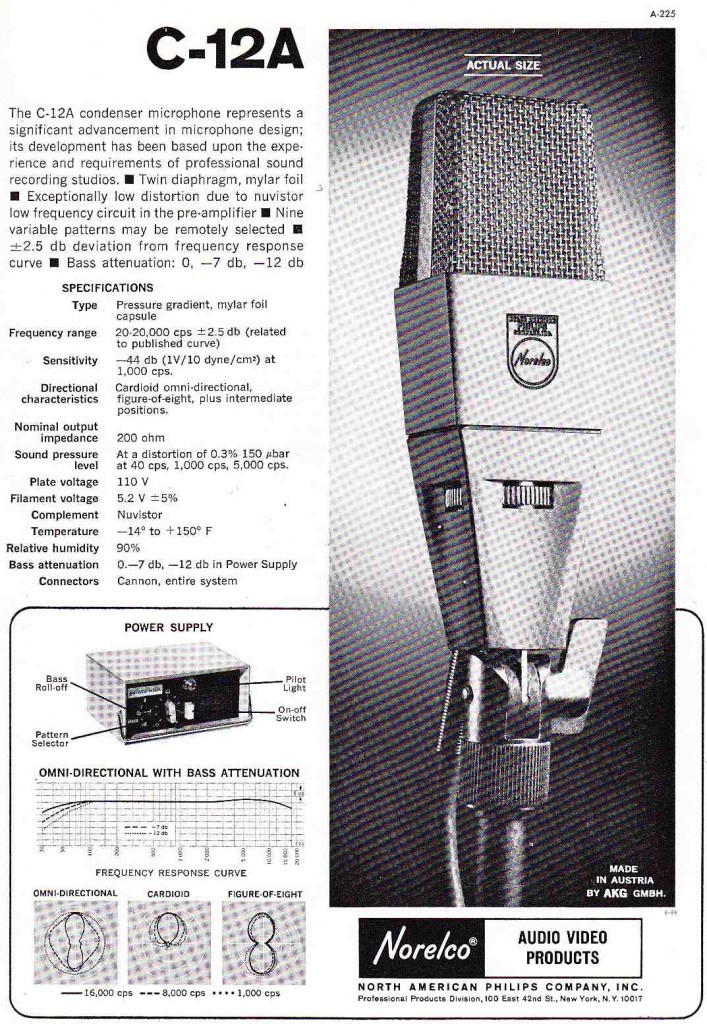

The AKG line-up from 1965, branded and distributed in the USA by Norelco. I recently came across a large trove of 1970s AKG dealar literature which I will feature soon on the site. The only mic from this 1965 stable that I have much experience with is the D-19, aka the Ringo Overhead Mic. I have found it to be useful for ‘distressed’ rock vocals, as well as aggressive driving acoustic guitar rhythm tracks.

The AKG line-up from 1965, branded and distributed in the USA by Norelco. I recently came across a large trove of 1970s AKG dealar literature which I will feature soon on the site. The only mic from this 1965 stable that I have much experience with is the D-19, aka the Ringo Overhead Mic. I have found it to be useful for ‘distressed’ rock vocals, as well as aggressive driving acoustic guitar rhythm tracks.

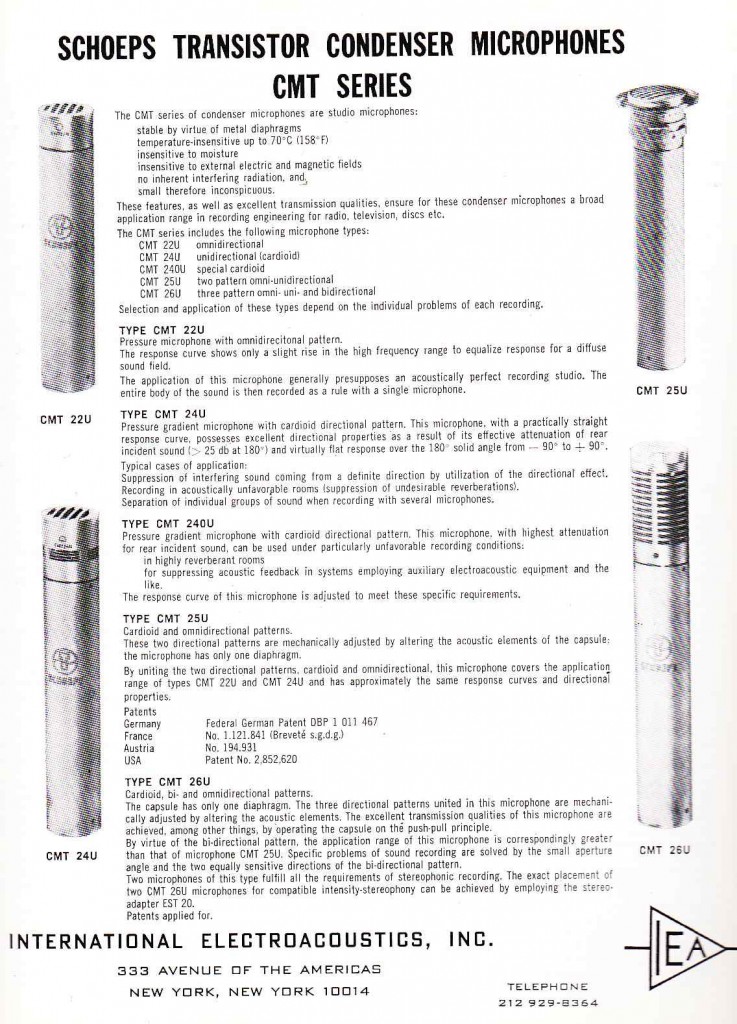

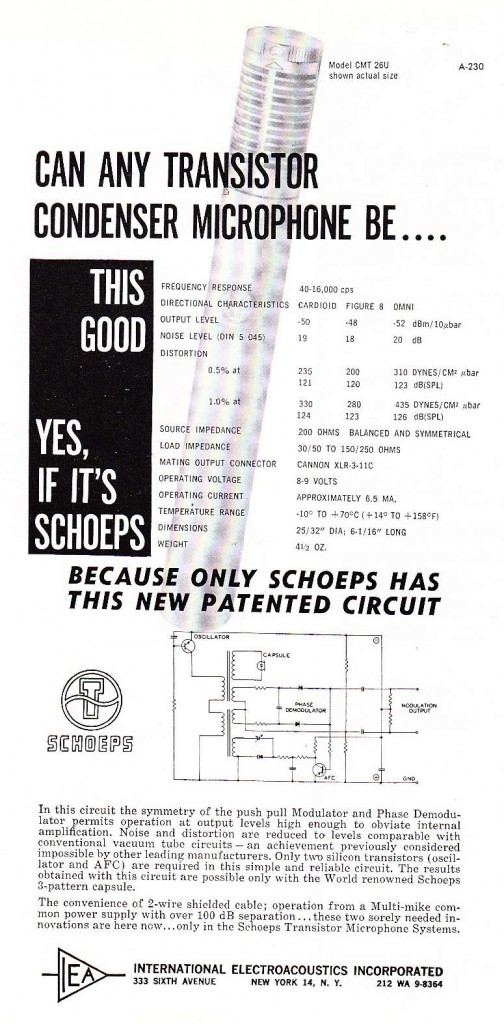

…And the Schoeps line. yup gotta get some of these.

…And the Schoeps line. yup gotta get some of these.

Tomorrow: Primitive electronic music studio.

Our earlier post on Saul Marantz discussed the journal of the Audio Engineering Society in general. This week we are going to take a closer look at some of these fascinating publications. We’ll start with a crop of microphones from the 1965 issues.

Our earlier post on Saul Marantz discussed the journal of the Audio Engineering Society in general. This week we are going to take a closer look at some of these fascinating publications. We’ll start with a crop of microphones from the 1965 issues.

For a time in the 1960’s, Norelco (the electric-razor people) branded and distributed AKG microphones in the United States. The AKG C12A was the historical bridge between two icons of pro audio: the legendary 6072-tube driven C12, and the perennial AKG 414. If you have been following this blog you will recognize the AKG 414 as my ‘reference’ microphone. I have two 414s – an older 414 XLS and one of the newer 414Bs. The 414 is, basically, the cheapest (around $1000) widely-used multi-pattern microphone for professional applications. Most audio-folk are familiar with the 414 sounds, so i feel like it makes for a good sonic reference point.

For a time in the 1960’s, Norelco (the electric-razor people) branded and distributed AKG microphones in the United States. The AKG C12A was the historical bridge between two icons of pro audio: the legendary 6072-tube driven C12, and the perennial AKG 414. If you have been following this blog you will recognize the AKG 414 as my ‘reference’ microphone. I have two 414s – an older 414 XLS and one of the newer 414Bs. The 414 is, basically, the cheapest (around $1000) widely-used multi-pattern microphone for professional applications. Most audio-folk are familiar with the 414 sounds, so i feel like it makes for a good sonic reference point.

Unlike the 6072 (aka hi-grade 12AY7) powered C12 or the solid-state (aka transistor-driven) 414, The C12A uses a Nuvistor to provide capsule gain. The Nuvistor is a fascinating device. They are essentially miniature vacuum tubes which were assembled entirely in vacuum chambers. If the transistor had ‘never happened,’ Nuvistors might have represented the future of active circuitry. I don’t know of any current-manufacture audio equipment that uses these odd devices. Anyone?

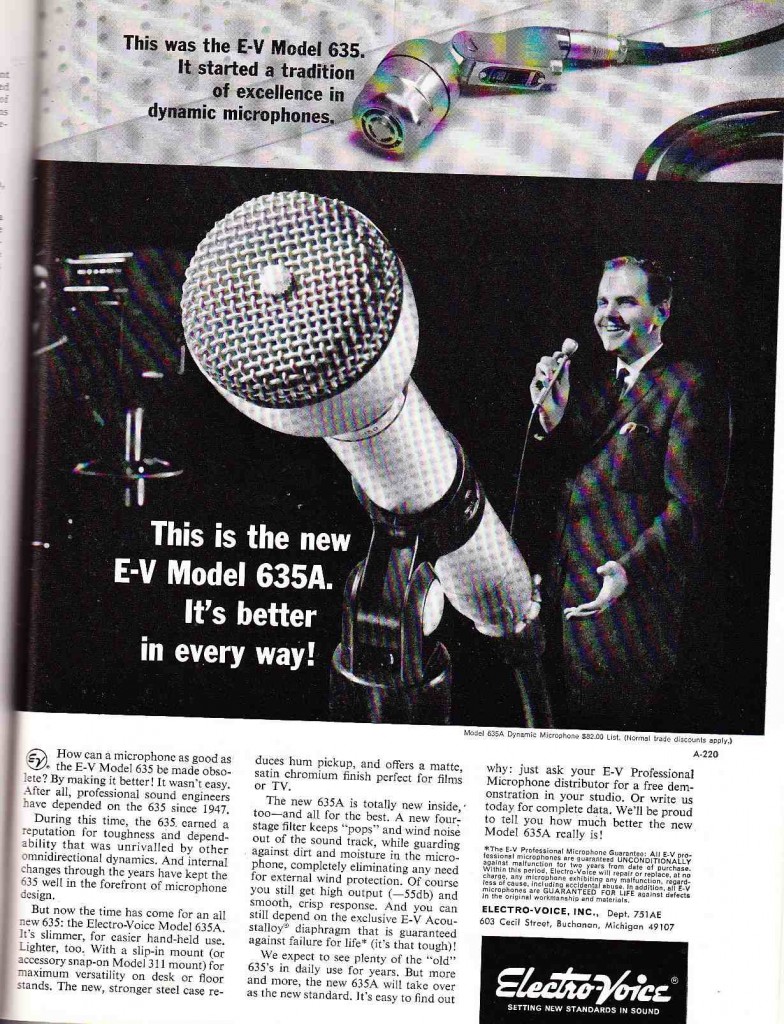

Ah. The Electro-voice 635A. The ‘Buchanan Hammer.’ These used to be as ubiquitous as Shure SM57s. Unlike most modern dynamic mics, the 635 is omnidirectional (picks up sound from all sides), so they are not so popular these days for music-studio-recording. I hope to do a listening-test with the 635 soon, side by side with a 57. BTW, 55 years later: EV still makes this product. Wow.

Ah. The Electro-voice 635A. The ‘Buchanan Hammer.’ These used to be as ubiquitous as Shure SM57s. Unlike most modern dynamic mics, the 635 is omnidirectional (picks up sound from all sides), so they are not so popular these days for music-studio-recording. I hope to do a listening-test with the 635 soon, side by side with a 57. BTW, 55 years later: EV still makes this product. Wow.

In an earlier post, I discussed a pair of EV 655s that I came across. Unlike the EV 635, the much costlier 655 is no longer being manufactured. The 655 seems to have been replaced by the (also discontinued) RE55 sometime in early 1970s. Expect a listening test of my 655s soon.

In an earlier post, I discussed a pair of EV 655s that I came across. Unlike the EV 635, the much costlier 655 is no longer being manufactured. The 655 seems to have been replaced by the (also discontinued) RE55 sometime in early 1970s. Expect a listening test of my 655s soon.

Yup, Schoeps mics are great. Need to get a few…

Yup, Schoeps mics are great. Need to get a few…

Has anyone been using Sennhesier 211s? The 211 is a small omni-directional dynamic mic. I am very curious to try these out. A couple of these sold on eBay for $150/ea a few weeks back. Drop a line if you have an opinion on the 211.

Has anyone been using Sennhesier 211s? The 211 is a small omni-directional dynamic mic. I am very curious to try these out. A couple of these sold on eBay for $150/ea a few weeks back. Drop a line if you have an opinion on the 211.

Tomorrow: deeper into the AES c. ’65.

Listen to this audio.

You don’t need me to tell you that this is the sound of an electric guitar playing through a guitar amp (speaker). You would believe me if I told you this was what you were hearing.

***********

*******

***

But what about the space that this happening in? And what does the sonic event of this speaker-movement sound like in that space? I can show you.

…And you would believe me that this is the space in which this event is taking place.

***********

*******

***

Humans are pretty good at using our ears/brain to evaluate a sound and judge the space in which that sound is occurring. We never had to do this much until about 100 years ago, because until we had technology to record/transmit and playback sound as audio, the only way to hear a sound was to be physically present where the sound was being generated. So baring blindness or blindfold, if you heard a sound, you did in fact have good direct knowledge of the space in which the sound was occurring. But we now have the technology to capture and reproduce sounds divorced from their origin in time and/or space. And we also have devised technologies to synthesize the sound of spaces. We can synthesize very good imitations of real physical spaces that we have experienced in the flesh. And we can also synthesize the effect of imaginary and unreal spaces.

Listen to the guitar performance again.

I have taken the close-mic’d guitar-audio you listened to initially and ‘placed it’ into a ‘church-space’ by processing it with a computer-reverb program. There is no actual physical space captured here, other than the 2-inches between the microphone and the speaker. But, if we suspend that knowledge, I think that we can all reasonably accept that yes it does in fact sound like the guitar-performance is taking place here:

Many generations of computer-programmers have labored for decades to create that sonic illusion, and they have done a pretty good job at it. Even the cheapest pieces of audio-hardware nowadays come with these digital-reverb programs built-in, and there are generally dozens of ‘spaces’ on offer, from Halls to Churches to Rooms etc. And most of the time, these reverb-programs are effectively able to convince us of the spaces that their names suggest.

But what about spring reverb? AKA., guitar-amp-reverb? AKA, the reverb knob on your old Fender (or whatever…) amp? Exactly what space is defined there?

Let’s take a listen. Here’s the same close-mic’d guitar performance you heard earlier; this time, though, I have turned on the reverb knob on the amp.

It’s evocative, right? But of what? And more importantly, of where? Our brain is telling us that the guitar is now in some sort of space. But what is that space? Well, literally, it’s the space and the springs inside this little 9-inch steel can in the back of the guitar amp.

But emotionally, we don’t feel like we’re hearing the sound of this little sardine can. Instead, the guitar-performance (and our imaginations) have been transported to some sort of mythic Rock-Legend-Space. How is this possible? Because we have heard this same goddamn accutronics-reverb-tank sound a million trillion times since were little kids. Because nearly every good-quality guitar amplifier made in this country or any other between the years 1965 and 2000 had one of these little mechanisms in it. Furthermore, we never heard the sound of this ‘space’ when we were walking down the street, or to the kitchen in the middle of the night to get a snack (crunchy carrots). We have heard this space a zillion times always and only in context of Rock and Roll. Either on record, on the radio, or in a club watching a band on an elevated stage. Through these millions of associations, the sound created by that little metal can has come to represent a sort-of Mount Olympus of Rock and Roll.

Or, if you like, the Hall Of Justice of Rock.

***************

**********

******

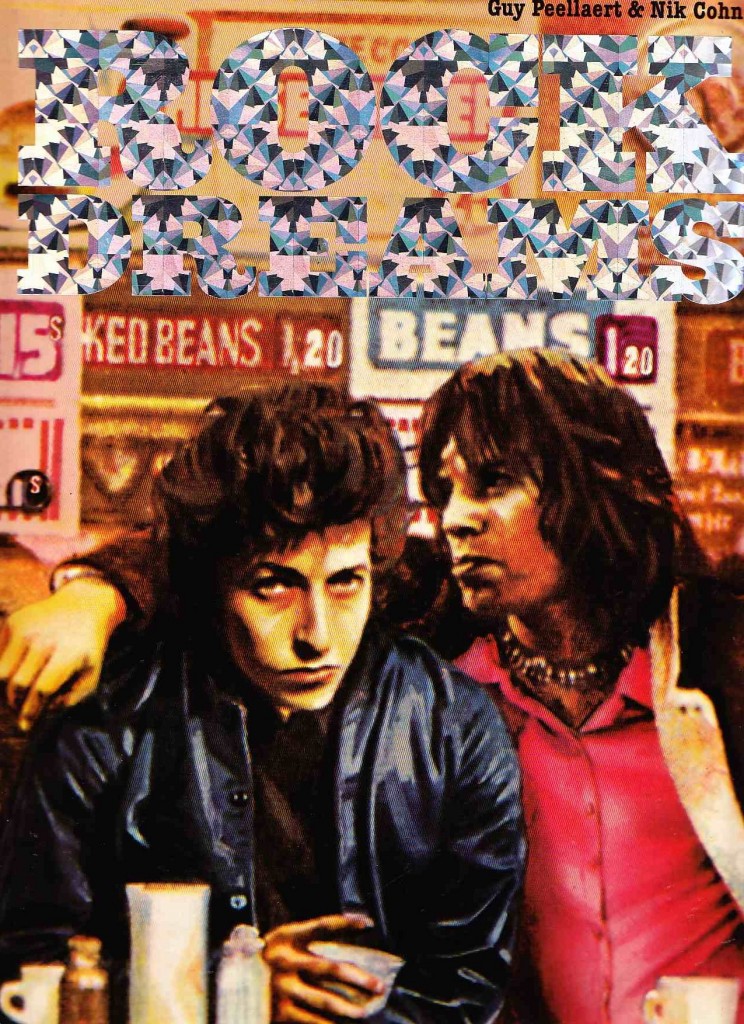

Have you ever read Rock Dreams by Peelaert and Cohn? It’s a collection of illustrations (with some explanatory text) that attempts to visualize the legends and myths that we associate with various Rock and Soul performers.

All of the personages represented in the illustrations are real, actual people who were born, lived, and died (or will). But they have been placed in settings which are simultaneously unreal and yet totally expected. The scenes depicted in the images are not actual places where these people ever set foot. Instead they are spaces that we have created in our collective imaginations. And they are very fitting.

All of the personages represented in the illustrations are real, actual people who were born, lived, and died (or will). But they have been placed in settings which are simultaneously unreal and yet totally expected. The scenes depicted in the images are not actual places where these people ever set foot. Instead they are spaces that we have created in our collective imaginations. And they are very fitting.

I think the spring-reverb box in the guitar amp has come to define such a space. Not a space of inches and miles, walls and ceilings, tiles and columns; but an imagined space where Rock and Roll lives; an imagined space that we all imagine with uncanny similarity.

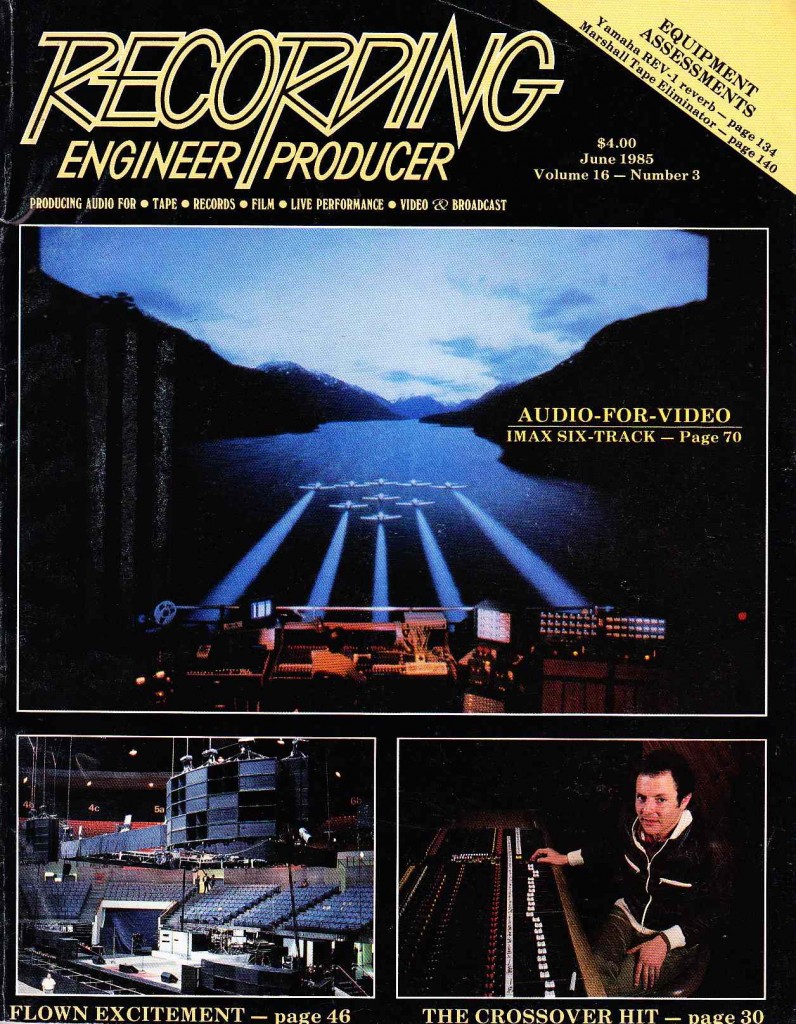

Recording Engineer/Producer Part III

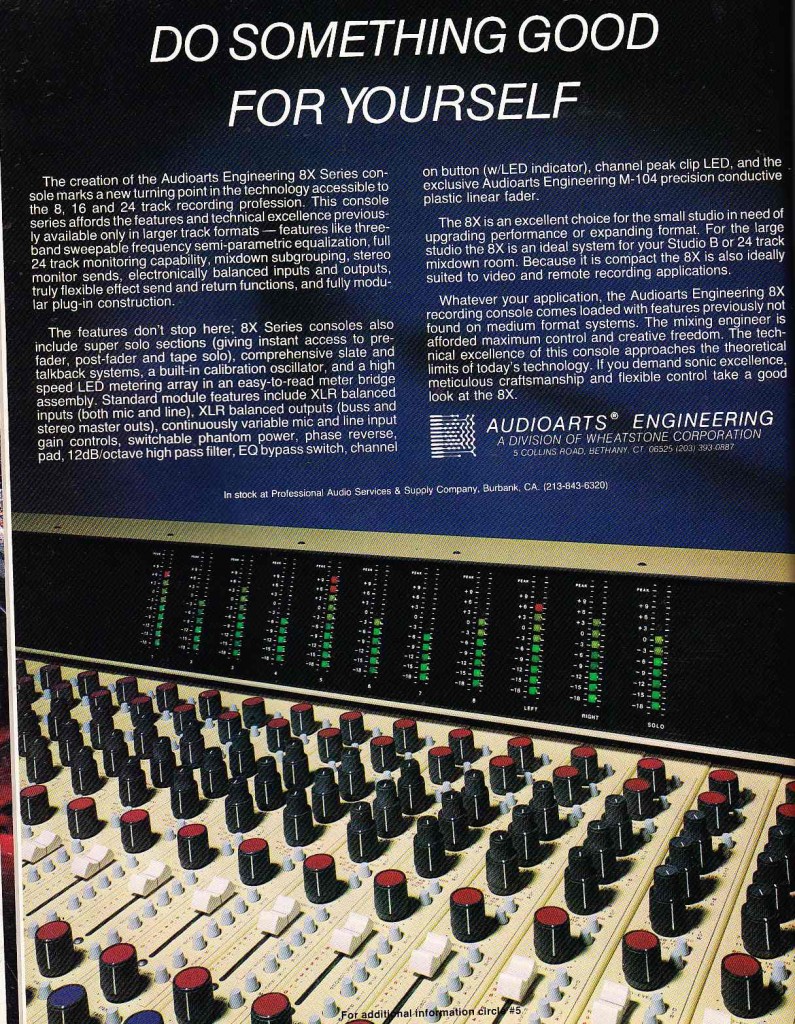

Spent yesterday doing some tech work in a time-capsule circa 1983 recording studio. Today’s perusal of RE/P Magazine c.’85 feels especially poignant.

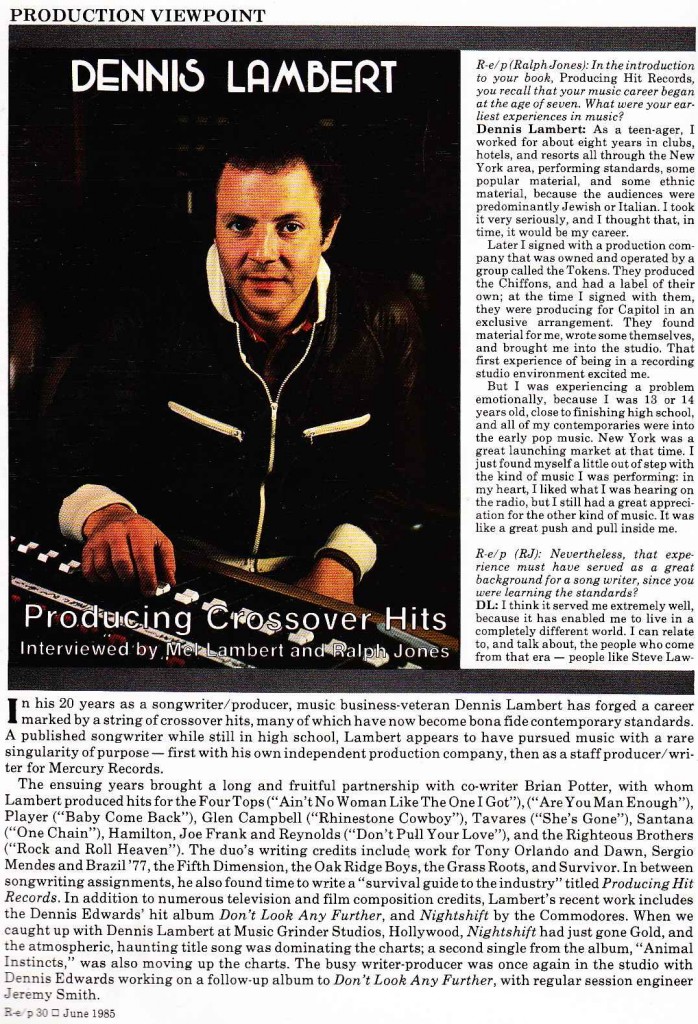

I had never paid attention to the name ‘Dennis Lambert’ before, but wow what a list of credits this dude has. The Four Tops ‘Ain’t no Woman Like The One I Got.’ Hamilton, Joe Frank, and Reynolds. Survivor. The Grass Roots. And Player’s ‘Baby Come Back.’

I had never paid attention to the name ‘Dennis Lambert’ before, but wow what a list of credits this dude has. The Four Tops ‘Ain’t no Woman Like The One I Got.’ Hamilton, Joe Frank, and Reynolds. Survivor. The Grass Roots. And Player’s ‘Baby Come Back.’

RE/P identifies Lambert as a master of the ‘Crossover Hit,’ which basically means that his music has an incredibly broad appeal that spans multiple listening tastes. Based on his credits, I think this is accurate. Dude had a book published called “Producing Hit Records,” and I think he earned the right. This interview was conducted as his active career was coming to a close.

RE/P identifies Lambert as a master of the ‘Crossover Hit,’ which basically means that his music has an incredibly broad appeal that spans multiple listening tastes. Based on his credits, I think this is accurate. Dude had a book published called “Producing Hit Records,” and I think he earned the right. This interview was conducted as his active career was coming to a close.

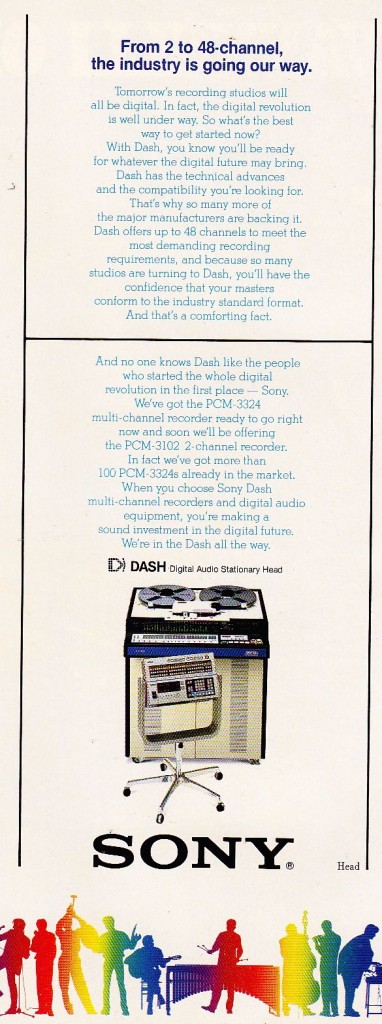

Sony Electronics recently unveiled a new product called the SONY DASH. It is a ‘personal internet viewer,’ sort-of like a clock radio-meets- iPad. I worked on the product launch for months as music-supervisor and never once did I recall that SONY actually had a major pro-audio product named DASH in the 80’s/90’s. The DASH digital-multitrack has vanished to that great of a extent. Crazy. These gigantic, expensive machines were the historical bridge between 24-track analog tape and DAWs like Pro Tools. A lot of really, really big records were recorded on the DASH, but at this point, they offer neither the ‘sound’ of analog tape nor the convenience/editing ability of DAWs. God only knows where these monsters have ended up. Feel like I saw one of eBay for like $1500 last year.

Sony Electronics recently unveiled a new product called the SONY DASH. It is a ‘personal internet viewer,’ sort-of like a clock radio-meets- iPad. I worked on the product launch for months as music-supervisor and never once did I recall that SONY actually had a major pro-audio product named DASH in the 80’s/90’s. The DASH digital-multitrack has vanished to that great of a extent. Crazy. These gigantic, expensive machines were the historical bridge between 24-track analog tape and DAWs like Pro Tools. A lot of really, really big records were recorded on the DASH, but at this point, they offer neither the ‘sound’ of analog tape nor the convenience/editing ability of DAWs. God only knows where these monsters have ended up. Feel like I saw one of eBay for like $1500 last year.

Here we have a competing digital multi-track from Mitsubishi.

Here we have a competing digital multi-track from Mitsubishi.

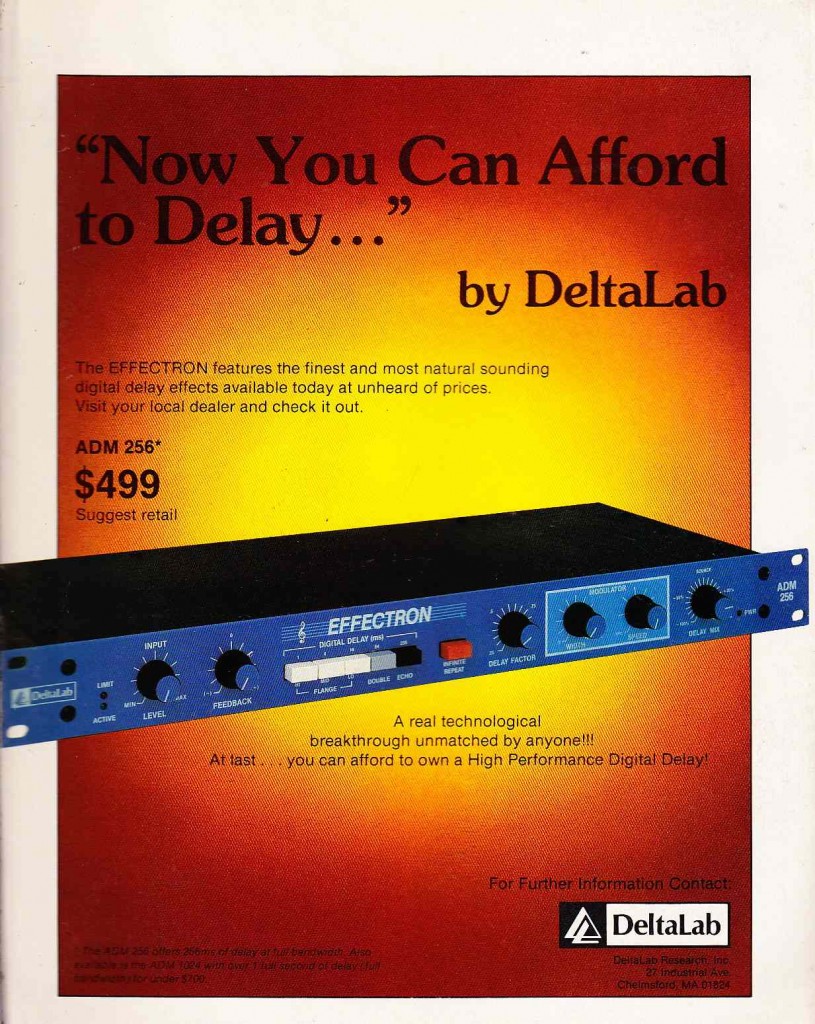

Effectron! What happened? Where did your knobs go? Bad move guys. Unlike the circa ’82 blue Effectron with the great, tactile interface, this later digitally-controlled version was not a hit.

Effectron! What happened? Where did your knobs go? Bad move guys. Unlike the circa ’82 blue Effectron with the great, tactile interface, this later digitally-controlled version was not a hit.

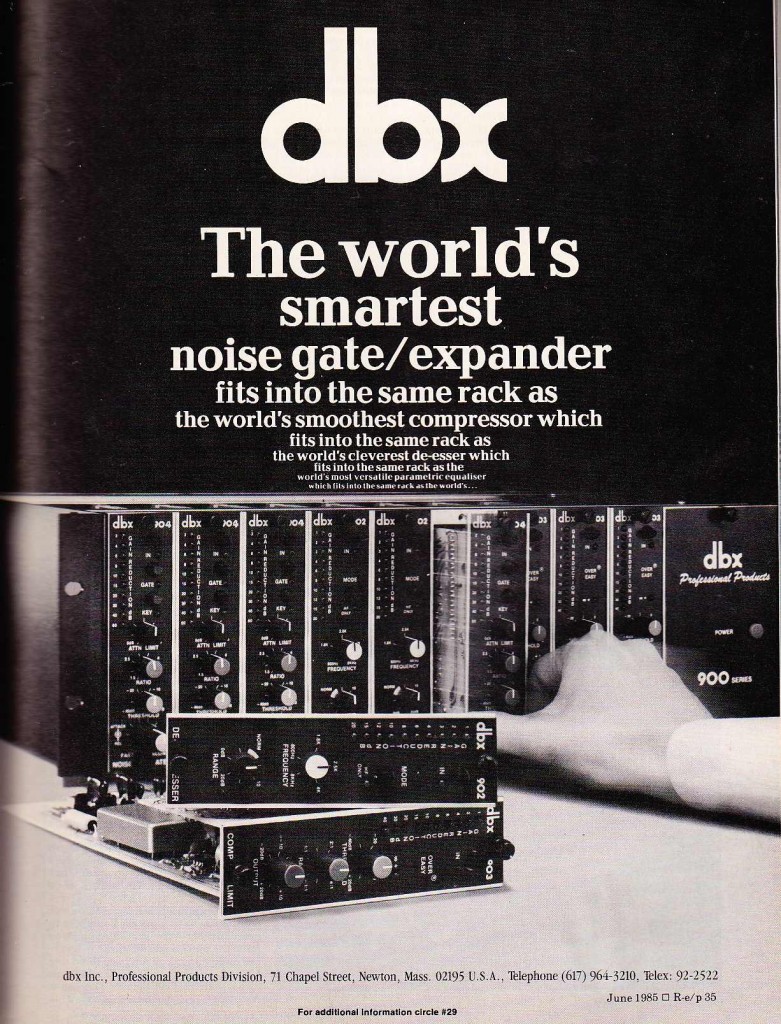

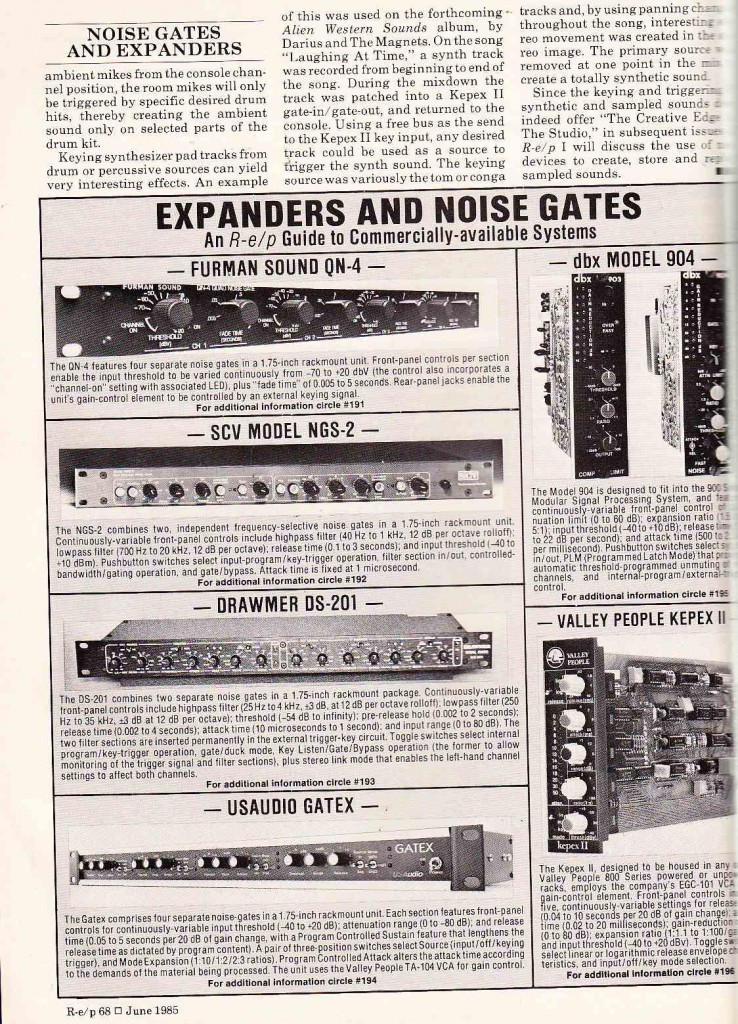

Love, love my DBX 900 rack. I have five 903 compressor cards, one 902 De-esser, and 2 of the gates. These are a great value in outboard gear and they take up so little space. Highly recommended.

Love, love my DBX 900 rack. I have five 903 compressor cards, one 902 De-esser, and 2 of the gates. These are a great value in outboard gear and they take up so little space. Highly recommended.

As much as I like older audio equipment, I do not miss hardware gates. Not at all. Thank you Pro Tools and the Digital Hygiene that you make possible. There are certainly many creative applications for these devices, but overall this is functionality that is much better served by the DAW.

As much as I like older audio equipment, I do not miss hardware gates. Not at all. Thank you Pro Tools and the Digital Hygiene that you make possible. There are certainly many creative applications for these devices, but overall this is functionality that is much better served by the DAW.

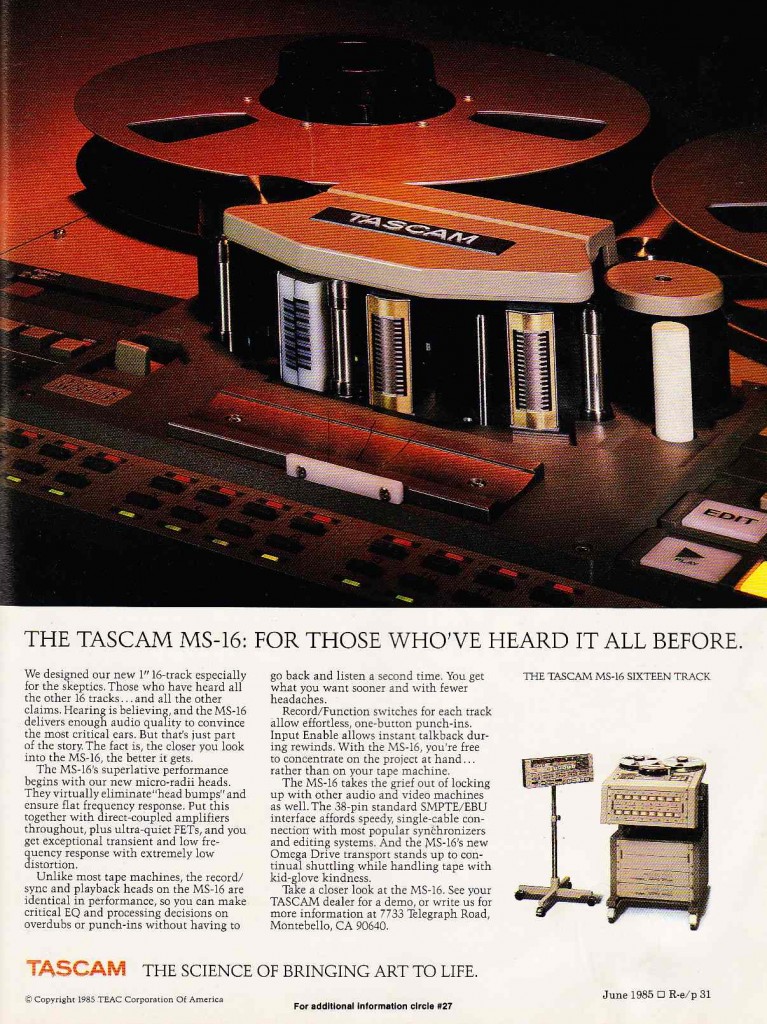

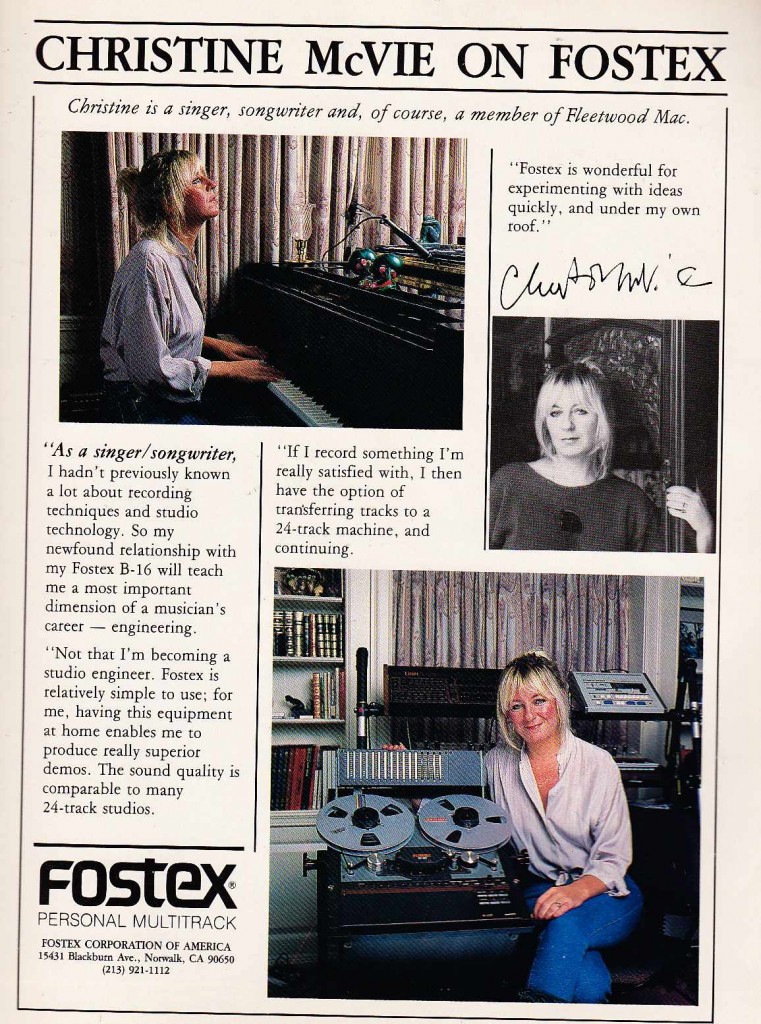

Seems like a pleasant lady. Interesting how FOSTEX is really going after the non-technical-person market here. As-in., “I write songs. I want to record them. Don’t care about specs ETC. Here’s a pic of me writing a tune. Here I am looking pensive. Also here’s the product.” TASCAM had a very similar product range at the time, but conversely, they wanted to convince you that their 16-track 1″ machine was ‘actually serious kit, for real!’

Seems like a pleasant lady. Interesting how FOSTEX is really going after the non-technical-person market here. As-in., “I write songs. I want to record them. Don’t care about specs ETC. Here’s a pic of me writing a tune. Here I am looking pensive. Also here’s the product.” TASCAM had a very similar product range at the time, but conversely, they wanted to convince you that their 16-track 1″ machine was ‘actually serious kit, for real!’

Recording Engineer/Producer Part II

Looking through the August and October 1983 issues of RE/P today.

What has changed since 1982? There is an even bigger focus on digital recording – primarily new 2-channel Digital Mastering platforms. There is also more discussion of Dolby noise-reduction. This is certainly the direction that the 1980s were heading.

What has changed since 1982? There is an even bigger focus on digital recording – primarily new 2-channel Digital Mastering platforms. There is also more discussion of Dolby noise-reduction. This is certainly the direction that the 1980s were heading.

Today I will be going to a local studio to (attempt) to service the 1983 NEVE console installed there. I don’t think it has been switched on for 10 years. Wish me luck. Expect a full report soon….

Today I will be going to a local studio to (attempt) to service the 1983 NEVE console installed there. I don’t think it has been switched on for 10 years. Wish me luck. Expect a full report soon….

Speaking of Connecticut: when I was growing up, ‘Eastcoast Sound’ was the local guitar store. It was a gigantic cavernous former roller-rink (or so i heard…) steps from Candlewood Lake in Danbury CT. Where FOREIGNER songs will blast from small-power boats until the end of time. Anyhow, I had pretty mixed experience with Eastcoast. Some good deals on used guitars and amps; not always the most professional salespeople. A couple of years ago I came across this little gem on Youtube. Incredible but true:

Speaking of Connecticut: when I was growing up, ‘Eastcoast Sound’ was the local guitar store. It was a gigantic cavernous former roller-rink (or so i heard…) steps from Candlewood Lake in Danbury CT. Where FOREIGNER songs will blast from small-power boats until the end of time. Anyhow, I had pretty mixed experience with Eastcoast. Some good deals on used guitars and amps; not always the most professional salespeople. A couple of years ago I came across this little gem on Youtube. Incredible but true:

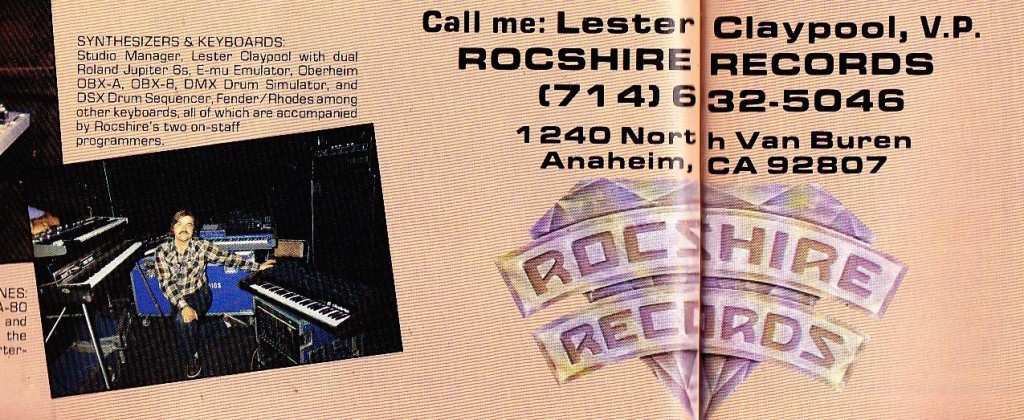

OK. We’ve got Anaheim CA in 1983. We’ve got a studio employee named Les Claypool. He has a mustache. Draw your own conclusions.

OK. We’ve got Anaheim CA in 1983. We’ve got a studio employee named Les Claypool. He has a mustache. Draw your own conclusions.

I would certainly buy a new Echoplate 3 for $1700. Kinda miss 1983 right now.

I would certainly buy a new Echoplate 3 for $1700. Kinda miss 1983 right now.

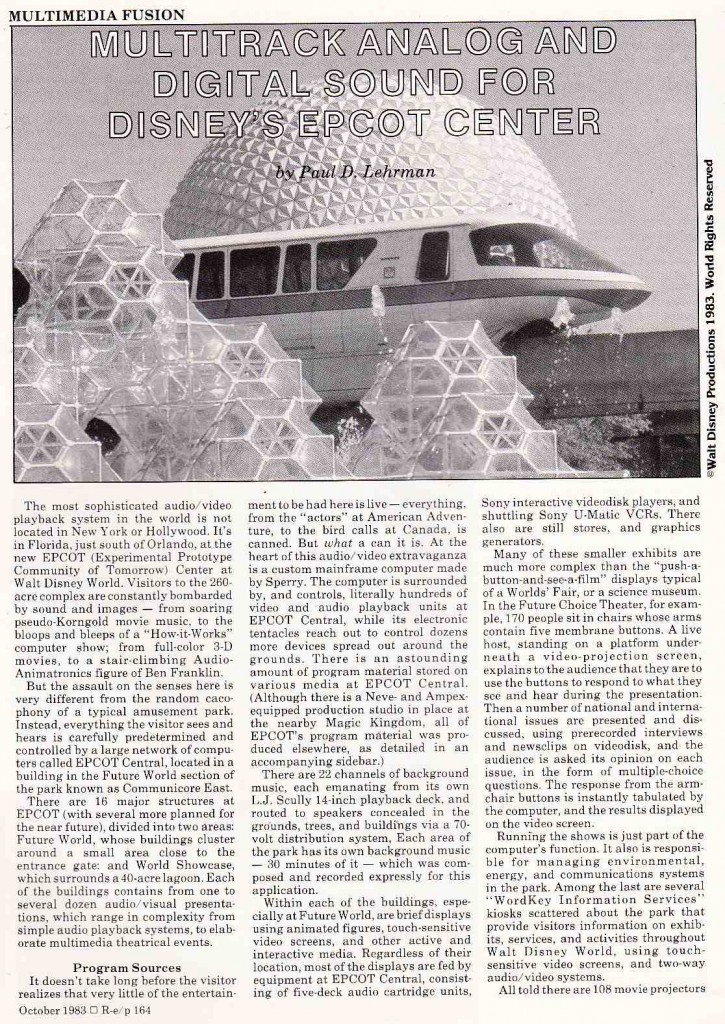

Epcot Center: a true American icon on the 1980’s. Here we get an in-depth study of the sound system installed there.

Epcot Center: a true American icon on the 1980’s. Here we get an in-depth study of the sound system installed there.

OK this is going to go on for a while… So follow the link below to READ ON…

Commercially Marketable Product

Decided to stick with the ‘recording mag circa 81’ theme for a little while longer. For the rest of the week we will be taking a look at “Recording Engineer/Producer” magazine in the early 1980s.

“Recording Engineer/Producer” (hf. RE/P) was published between 1971 and 1992. Read a quick and educational ‘love-letter’ to RE/P here. We can roughly pin this as the time-span between the first affordable multi-track tape tape machines and the dawn of the ADAT, which was the first home-recording digital multitrack machine. I am not suggesting that these particular pieces of technology were uniquely responsible for the fate of this publication but it interesting to note none-the-less.

If we can safely assume that “Modern Recording And Music” (see previous posts here and here) was aimed at home-recordists, RE/P is very clear that it is aimed at professional users working in commercial fields. And this is indeed a more technical, more advanced publication.

If we can safely assume that “Modern Recording And Music” (see previous posts here and here) was aimed at home-recordists, RE/P is very clear that it is aimed at professional users working in commercial fields. And this is indeed a more technical, more advanced publication.

Here’s a look at some of the content and products on display in October of 1982 from within the pages of RE/P.

Here’s a look at some of the content and products on display in October of 1982 from within the pages of RE/P.

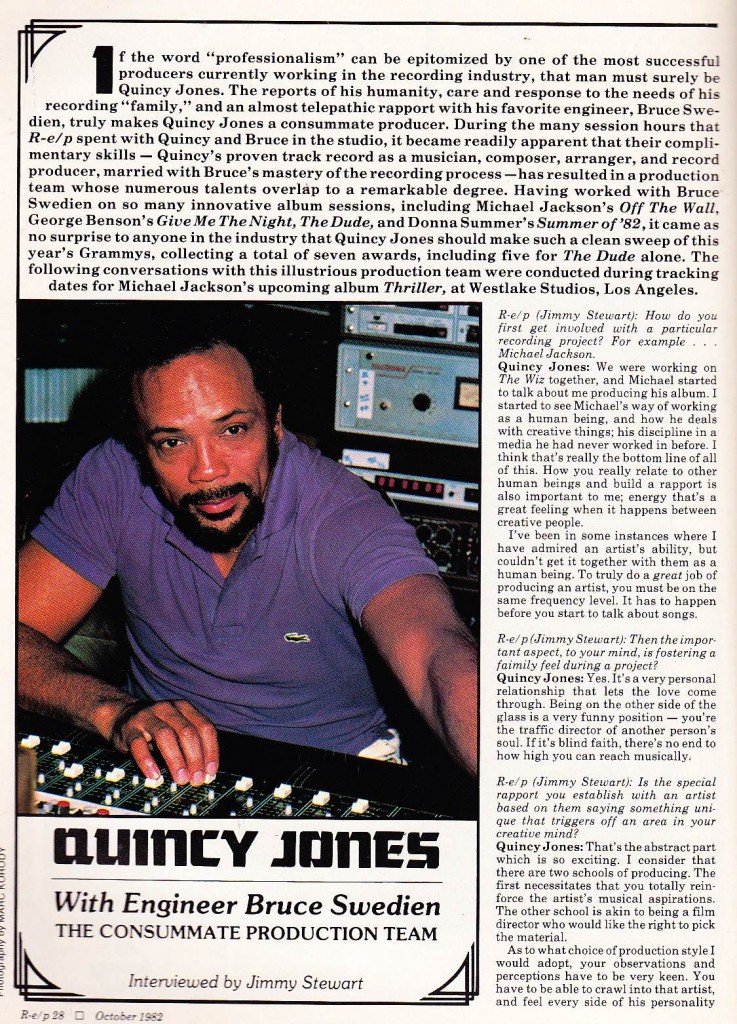

The unstoppable Q makes another appearance. This is a great article, with detailed notes on microphone and outboard gear techniques that Jones and Bruce Swedien were getting into at the time. Oh and what were they working on in late 82? A little record called THRILLER.

The unstoppable Q makes another appearance. This is a great article, with detailed notes on microphone and outboard gear techniques that Jones and Bruce Swedien were getting into at the time. Oh and what were they working on in late 82? A little record called THRILLER.

Man the Effectron is great. There are like a million of these things out there; i see them for as little as $50. Alright I am gonna put it on the line here; here is one of my very earliest studio productions featuring the device above. Circa 1996. I am not even going to try to explain this other than: if you can’t really sing… you can use an Effectron (or any other LFO time- modulated delay) to turn your vocal performance into something else entirely. Especially if the song/lyric is appropriate.

Man the Effectron is great. There are like a million of these things out there; i see them for as little as $50. Alright I am gonna put it on the line here; here is one of my very earliest studio productions featuring the device above. Circa 1996. I am not even going to try to explain this other than: if you can’t really sing… you can use an Effectron (or any other LFO time- modulated delay) to turn your vocal performance into something else entirely. Especially if the song/lyric is appropriate.

Our survey of this issue will go on for a while… so follow the link below to READ ON….

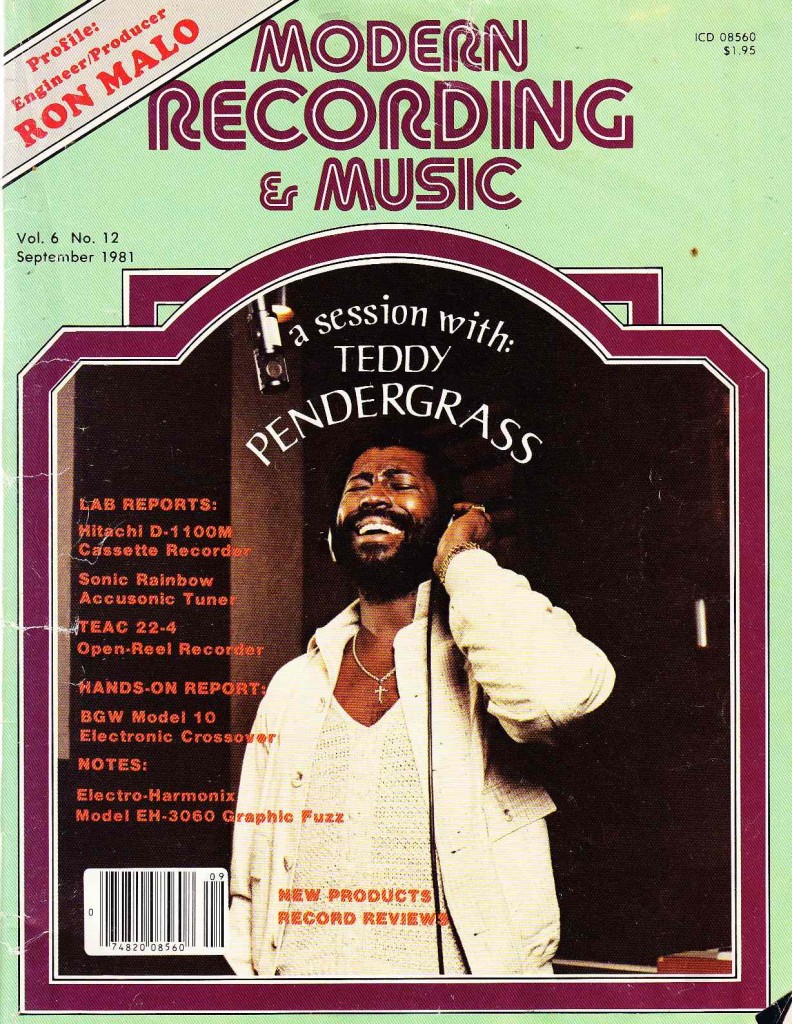

Modern Recording And Music Part 2

So. 5 years later. 1981. How had ‘home-recording’ coverage changed? The range of products had increased, certainly. There is still a focus here on consumer and prosumer tape decks and tape stock, vague ‘reader-questions’ such as “what does a producer do,” and of course the Teddy-Pendergrass tracking session notes. The publication does seem to have gotten more sophisticated though. We now see ads for expensive test equipment and console automation. Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting bits and bobs c. ’81.

So. 5 years later. 1981. How had ‘home-recording’ coverage changed? The range of products had increased, certainly. There is still a focus here on consumer and prosumer tape decks and tape stock, vague ‘reader-questions’ such as “what does a producer do,” and of course the Teddy-Pendergrass tracking session notes. The publication does seem to have gotten more sophisticated though. We now see ads for expensive test equipment and console automation. Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting bits and bobs c. ’81.

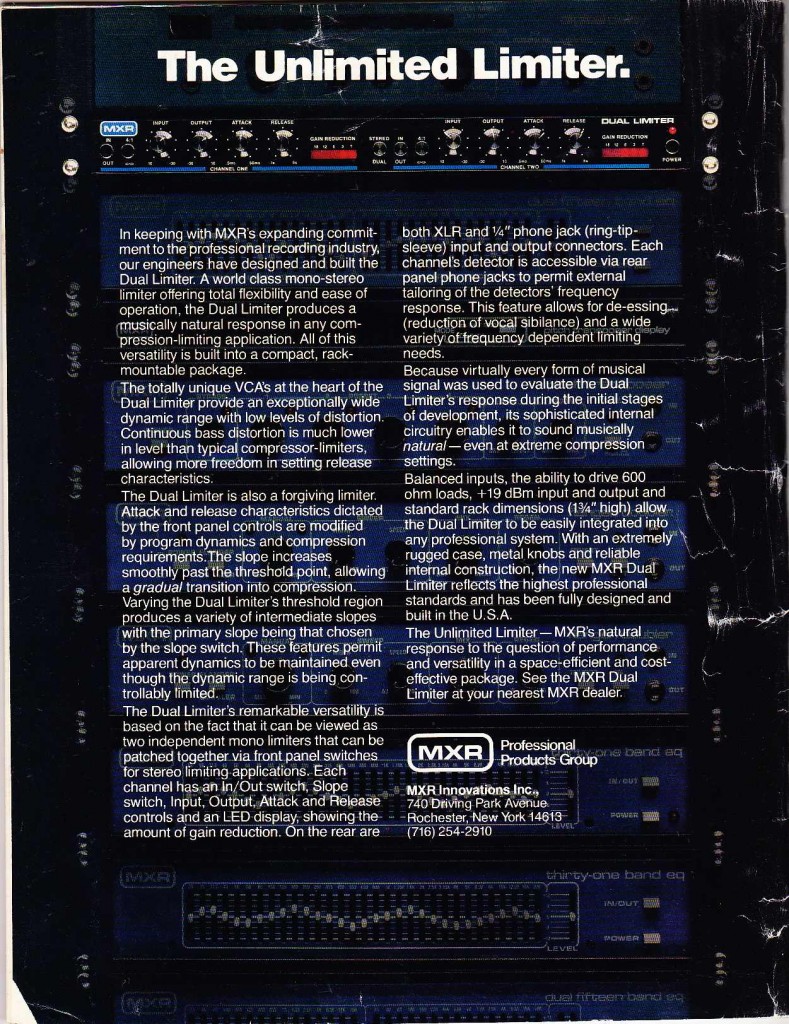

I have one of these MXR limiters. They can be purchased for under $100. Initially I used it often to group-compress drums together with bass for hip hop tracks; lately I’ve been using it for parallel drum compression and it works great for that. Very aggressive sound; quiet, good fidelity. The ‘channel-link’ button seems to do very little; also the input (or output?) gain is not matched between the channels; annoying to work around but it’s worth the hassles for the sound. Pick one up if you can.

I have one of these MXR limiters. They can be purchased for under $100. Initially I used it often to group-compress drums together with bass for hip hop tracks; lately I’ve been using it for parallel drum compression and it works great for that. Very aggressive sound; quiet, good fidelity. The ‘channel-link’ button seems to do very little; also the input (or output?) gain is not matched between the channels; annoying to work around but it’s worth the hassles for the sound. Pick one up if you can.

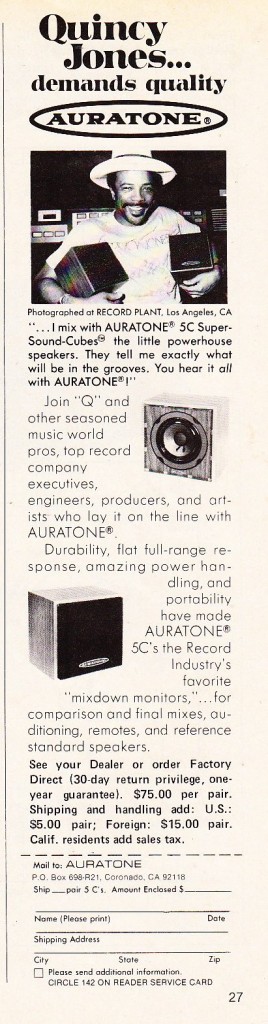

Q is right to demand his Auratones.  This is a truly great product. I had an old banged-up pair for years, and about 5 years ago I put a newly-manufactured pair of “Avantones” in their place. The Avantone is just as good, if not better. What are these speakers and why are they so good? First off, don’t believe the language in this ad. These speakers do not sound great, and they CERTAINLY do not give a mixer “all that will be in the grooves.” These speakers are ‘real-world reference speakers.’ Unlike big, expensive ‘Studio Monitors,’ Auratones/Avantones have no low end and no high end. They sound, instead, like the majority of actual speakers that normal people will actually hear your work on. This is crucial to mixing. In the audio-post-production (IE,. sound work for video mediums) world we call these ‘TV speakers.” As-in, ‘hey charlie, lemme hear it on the TV speakers.’ As-in, Auratones/Avantones sound pretty similar to the speakers that are built in to a decent TV set. But: even better: they can handle very high power. If you need to, you can put pretty heavy watts into these guys (well, at least the Avantones) and you will not damage them.

This is a truly great product. I had an old banged-up pair for years, and about 5 years ago I put a newly-manufactured pair of “Avantones” in their place. The Avantone is just as good, if not better. What are these speakers and why are they so good? First off, don’t believe the language in this ad. These speakers do not sound great, and they CERTAINLY do not give a mixer “all that will be in the grooves.” These speakers are ‘real-world reference speakers.’ Unlike big, expensive ‘Studio Monitors,’ Auratones/Avantones have no low end and no high end. They sound, instead, like the majority of actual speakers that normal people will actually hear your work on. This is crucial to mixing. In the audio-post-production (IE,. sound work for video mediums) world we call these ‘TV speakers.” As-in, ‘hey charlie, lemme hear it on the TV speakers.’ As-in, Auratones/Avantones sound pretty similar to the speakers that are built in to a decent TV set. But: even better: they can handle very high power. If you need to, you can put pretty heavy watts into these guys (well, at least the Avantones) and you will not damage them.

I love editing audio on the Avantones. They just sound good at low volume levels. Audio playback on really expensive speakers at low level always puts me off. If I have to spend 3 hours editing drums, i would much rather do it at a quiet level on these little guys. BTW – in my experience – artists generally hate these things. The artist will always prefer hearing playback loud, and on the expensive speakers. Be prepared.

I applaud Avantone for being straight-forward and celebrating their product as being ‘bass-impaired’ and ‘real-world.’ I think that if you had believed this 1981 ad and purchased a pair of Auratones as your main mixing speakers, you would have been very disappointed. As a 2nd or 3rd pair of studio speakers, tho, they are great.

Pretty incredible that tape stock once made such an enormous difference in the quality of your recordings. It is a similar concept as data compression today. But while bytes are basically free, i.e., we all seem to have more data-storage capacity than we need, regardless of the bit rates and sampling frequency that we chose, tape was expensive! I remember once purchasing a blank cassette tape for almost $60. The shell was made from a ceramic composite. What mix-tape could have possibly justified this expense? I think I was like 12 years old btw.

Pretty incredible that tape stock once made such an enormous difference in the quality of your recordings. It is a similar concept as data compression today. But while bytes are basically free, i.e., we all seem to have more data-storage capacity than we need, regardless of the bit rates and sampling frequency that we chose, tape was expensive! I remember once purchasing a blank cassette tape for almost $60. The shell was made from a ceramic composite. What mix-tape could have possibly justified this expense? I think I was like 12 years old btw.

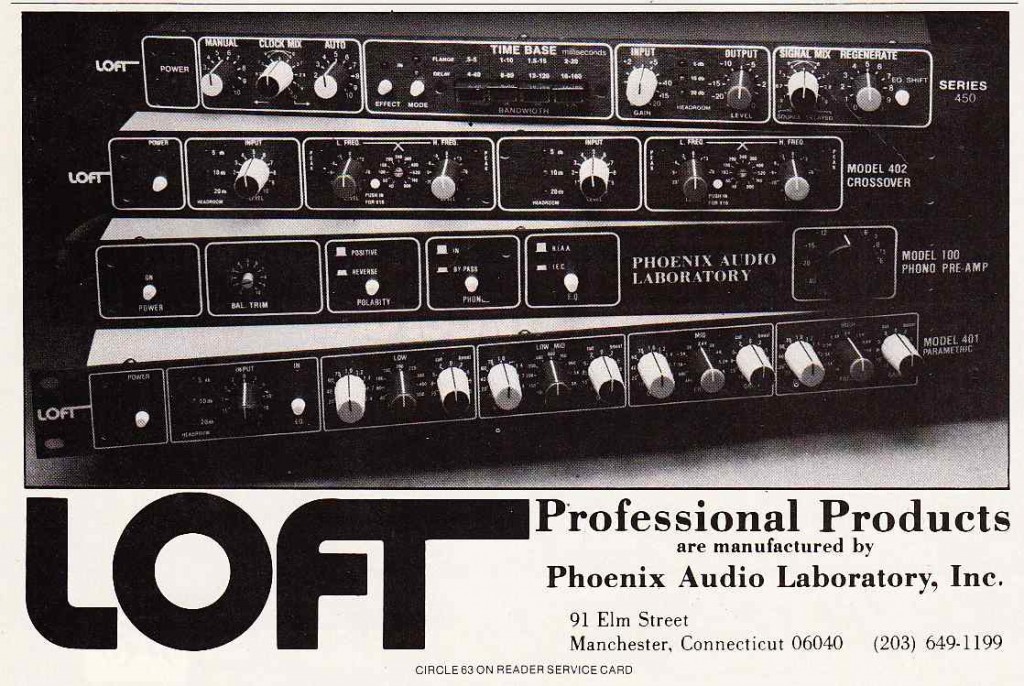

Nice. Another piece of CT pro-audio history. I recently came upon a large folio of original documentation on the entire ‘Loft’ line. There is very little information on the web about this short-lived manufacturer, other than the later employment of its founder Peter J. Nimirowski. Looks like this man ran fast+far from the pro audio world. If I can ever scare up a piece of this hardware I plan to write a feature on them.

Nice. Another piece of CT pro-audio history. I recently came upon a large folio of original documentation on the entire ‘Loft’ line. There is very little information on the web about this short-lived manufacturer, other than the later employment of its founder Peter J. Nimirowski. Looks like this man ran fast+far from the pro audio world. If I can ever scare up a piece of this hardware I plan to write a feature on them.

Update: Peter got in touch with PS.com after we published this article. Peter tells us that he stayed involved with LOFT for several years after the firm was sold. Peter also turned us on to the existence of LOFT consoles. We have no information regarding these consoles in the archive, so if anyone out there can share any images/data ETC., please do.

Ah. The classic. These Technics decks just look so great, and they sound great too. I had 3 or 4 of these at one time, literally pulled from the dumpster of an Ad Agency that ran out of storage space. Someday another will turn up. I don’t believe that these decks had balanced I/O, which would put them well in the camp of consumer audio gear, but if I remember right the sound quality was on par with any Tascam or Otari 50/50 that I ever owned.

Ah. The classic. These Technics decks just look so great, and they sound great too. I had 3 or 4 of these at one time, literally pulled from the dumpster of an Ad Agency that ran out of storage space. Someday another will turn up. I don’t believe that these decks had balanced I/O, which would put them well in the camp of consumer audio gear, but if I remember right the sound quality was on par with any Tascam or Otari 50/50 that I ever owned.

********************

***********

The biggest development of the year in audio, however, was no fleeting piece of hardware: it was a new audio-product-delivery technology that would forever change the world of music and audio. The Compact Digital Audio Disc. The CD.

There has been a lot of discussion about the recent decline of the Recording-Industry. A lot of accusations of poor moral decision-making on the part of music (non) purchasers; a lot of charges of greed and short-sightedness on the part of the industry; a lot of chatter that this was all ‘inevitable’ due to ‘information sharing’ in the ‘internet age.’

Can we consider, though, that perhaps it was not illegal file-sharing that began the collapse of the economic basis of the Recording Industry. Perhaps instead we can trace the problem to the decision to encode consumer audio as data. To forever free audio from issues of mechanical reproduction and the consequent loss of fidelity that occurs every time a mechanical copy (be it magnetic tape or embossed disc) is made. Once the Recording Industry made the decision to offer these digital copies (I.E., CDs) of their content for sale, they essentially surrendered the one piece of control that they possessed up to that point: The ability to manufacture clones of their products which were identical in quality to the original. By making and marketing CDs of their recordings, Record Companies essentially gave away the privileged access that they once had sole control over.

Sure, there were bootleg LPs and Tapes sold before 1981. But they did not, COULD NOT, sound as good as a Label copy. A bootleg CD sounds exactly the same as a Label CD. It has to. And a downloaded WAV file ripped from a CD sounds exactly the same as a label CD. It has to.