If you are a musician or serious rock music fan, you will know what the term ‘demo’ refers to in the context of recorded music. ‘Demo’ is shorthand for ‘demonstration record(ing).’ IE., a recording which is not intended for public commercial exploitation, but rather to demonstrate the assets of the various artists involved to the industry. Which various artists? Generally speaking, demos are made by bands (musical performers with or without vocals), solo or group vocalists, and songwriters. Demos are made in the hope of getting the attention of record labels, song publishers, other artists who are looking for new songs to record, club and concert bookers, etc. Demos are generally ‘rougher’ and ‘less produced’ than commercial masters. This is for a few reasons: first off, demos are usually part of the process involved in GETTING a paying deal or getting a paying project green-lit, so there will be less money behind them. Another reason is that since demos are made for an audience that is supposedly experienced and knowledgeable, demos can be a little ‘rougher’ since this special audience should be able to ‘hear past’ the rough quality and easily imagine what the band/singer/song will sound like once someone puts more time (and money) behind it. This ability to correctly see ahead, past the performance flaws and technical imperfections of a ‘demo,’ is what will allow a record company scout, talent agent, or song publisher to key into top-quality talent early, thereby potentially getting themselves a better deal on this new property.

There is a lot of mystique and even superstition surrounding demos in the music/recording world. People will speak of ‘demo love,’ AKA the condition wherein the commercial master can’t seem to eclipse the emotional impact that the demo manages to achieve. On the other hand, some people will tend to apologize for their demos, even though their particular demo may be the best recording achievable on their budget, and even though it is the job of those in The Industry to ‘hear past’ the demo. Anyhow, I am not interested so much in the operation of demos in their contemporary context, but rather, the special qualities that we can experience in the demos of the past.

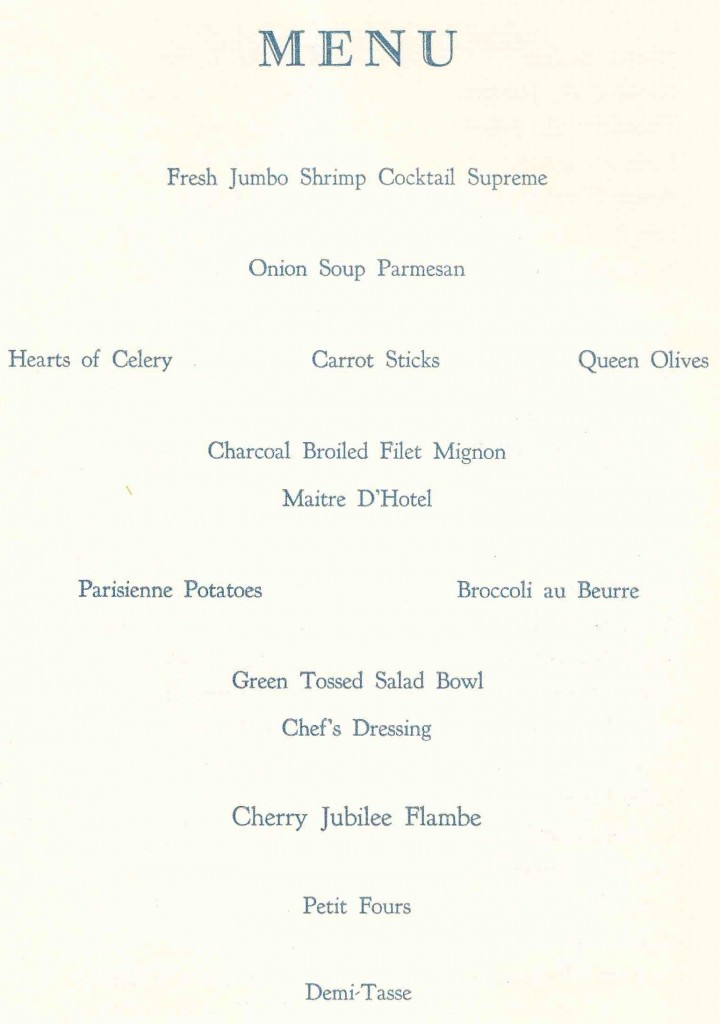

Here’s a songwriting demo from Jim Ford, an obscure soul songwriter most active in the early 70s. Several collections of his songwriting demos (demos created to ‘pitch’ his new compositions to artists who might potentially record them, thereby earning Ford and his publisher royalties on the recordings) were released in recent years by Bear Family, a German record company. It’s sloppy and crazy and messy and my god. It is cool.

16 Go Through Sunday

We generally agree that a demo is a ‘less produced’ recording. OK. but what does ‘produced’ mean? Record production is an art that involves a great many details, many of them incredibly specific to particular genres and trends and microtrends that may last for brief years or even months. Generally speaking, though, producing a commercial recording featuring some musical performers and a vocalist will involve, at minimum:

*)Some sort of dedicated recording space with the relevant tools and technology available (aka a ‘studio’).

*)The ability to capture multiple takes of a song, and edit between them if necessary.

*)A ‘producer’ who’s main minimum responsibility is essentially that of quality control – IE., someone with the authority and experience to say, “that’s the one.”

*)And, finally, time. Enough time to set up the equipment properly. Dither around with all the knobs and positions and instruments until the desired effect is truly achieved. And then do as many takes as needed, and afterwards, edit and mix and re-process all the various recorded audio signals until everyone who is invested in the project can say ‘what up, DONE?’

Let’s consider a typical example of a production task. Music production of instruments and especially vocals generally involves various electronic processes intended to enhance the sound of the performance. For instance: no one likes to hear a vocal that is not as well on pitch as the singer had intended. But if the singer just can’t nail it, what do you do? As an audio operator, you will employ various processes to either draw attention away from the flawed performance or even to correct the flaws. Until 1965 or so, this was done by adding reverberation and/or echo in order to ‘smooth out’ rough transitions between notes. (Try singing in the shower, or some other reverberant space, and you will notice that your signing sounds better!) Moving on, in the late 60s/1970s, aiding a pitchy-y vocal was often done by recording multiple takes of the same part and layering them on top of each other (a.k.a. ‘double tracking’ -made feasible because now you could have 16 or 24 separate tracks on a multitrack tape rather than just 4 or 8 tracks). by the early 80s and the advent of readily-available digital audio technology, you suddenly had the ability to ‘sample’ off pitch notes, correct the pitch, and then re-insert the corrected note into the performance. By the early 1990s and the dawn of the Digital Audio Workstation era, you had the ability to manipulate the performance basically however you wanted to. ANYTHING was ‘fixable’ given you had enough time and skill. And finally, by the late 1990s, we were given the technology commonly referred to as Auto Tune, by which a performance could be pitch-corrected nearly automatically, with very little skill or experience required even on the part of the audio operator.

So that’s the broad strokes, and one macro example, of music production. Back to my earlier line of inquiry: If a demo is a less-produced recording, then, a demo is basically a recording that is less manipulated. It has been subjected to less human-time spent modifying the audio. It is more simply the product of the performances and the physicality of the microphones, recording environment, and instruments that created the performances. Also, randomness and chance likely will play a bigger part in the finished result. None of what i am saying are absolutes – these are just generalizations. But in general, when we hear a demo from, say, 1970, we are given the chance to peer back in time in a way that produced commercial recordings don’t always allow us to. We can hear the way that an actual human drummer played a take In The Year 1970, as opposed to 7 recorded takes that were edited together and oh btw we tape-edited the drums in the bridge to really make it groove there. Is this better or worse? Neither. it’s different. It’s a matter of what you like. But, the demo will likely offer closer access to the performances and the actual sounds of the instruments/microphones/studio spaces that were used in ‘those days,’ whatever those days may be. I think in general, most people would associate ‘demo’ with ‘Lo Fidelity’ and ‘Studio Master’ with ‘Hi Fidelity,’ but when you think about it, a demo (so long as the recording equipment used was of decent quality) will actually bear much more fidelity to the actual acoustic event than a commercial master. We could get on a major sidetrack here about the quality of the equipment did matter back in the day/still matters today, but you catch my drift.

Have you ever seen ‘Shadows’ or any of the Cassevettes films? I was really struck by ‘Shadows’ when i first saw it at maybe age 18. My god, i had never heard people talk like that! Or move like that! Cassevettes as a director really relied on his actors to improvise, and therefore, I think his films offer us a better view into how people actually behaved back then. Sort of like what documentary films can offer. Granted, his ‘people’ were generally trained actors, but still. It’s less the work of a committee and more the work of One Person In Front Of A Camera. And for this reason, i feel like it gives me better access to that actual historical moment in which the film was made. I feel the same way about old demos. Here’s a really obscure recording from around 1970 that i found on a cut-rate compilation LP called ‘the now sounds.’ The LP contains recordings of various pop hits of the day, credited to basically anonymous vocalists. There is no information to be had on ‘jerry walsh’ or this recording. I imagine that it may have been recorded as a demo for this singer. Probably not for the band backing him, as there is a bad tape edit (or lack of an edit!) going into the guitar solo where the beat gets lost. If this had been created to the satisfaction of the band, the drummer would have likely not found this to be satisfactory. On the other hand, if the drummer was just hired to back up ‘Jerry’ that day, well…

04 Let It Be

Anyhow, yeah this is all conjecture on my part. Nonetheless, when i hear this recording, i feel like i am really getting a good sense of what it would have been like to hear an average singer, fronting an average band, in some average bar, anywhere in America in 1970. I’m not hearing The Entertainment Industry (which i have heard a million times, and it usually pretty much sounds the same). I ‘m just hearing some guys making a demo. And it’s evocative.

Does anyone out there collect and compile ancient publishing company demo recordings?

Is Jerry Walsh out there somewhere? Was this made as a demo?