Download a six-page excerpt regarding ‘the sound system’ from “Professional Rock And Roll” (Ed. Herbert Wise, Collier, 1967):

Download a six-page excerpt regarding ‘the sound system’ from “Professional Rock And Roll” (Ed. Herbert Wise, Collier, 1967):

DOWNLOAD: Professional_Rock_And_Roll_Excerpt

Very much along the lines of “Electric Rock” (1971) and “Starting Your Own Band” (1980), “Professional Rock And Roll” (h.f. “PRR”) is especially interesting in that it was published a mere three years after The Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan, an event which is widely considered to have marked the beginning of The Sixties Rock Era. In such a short span of time, enough of an industry and codified set of working-practices seems to have formed around young teen-oriented electric-guitar-based groups to have resulted in the large paperback that I now hold in my hand.

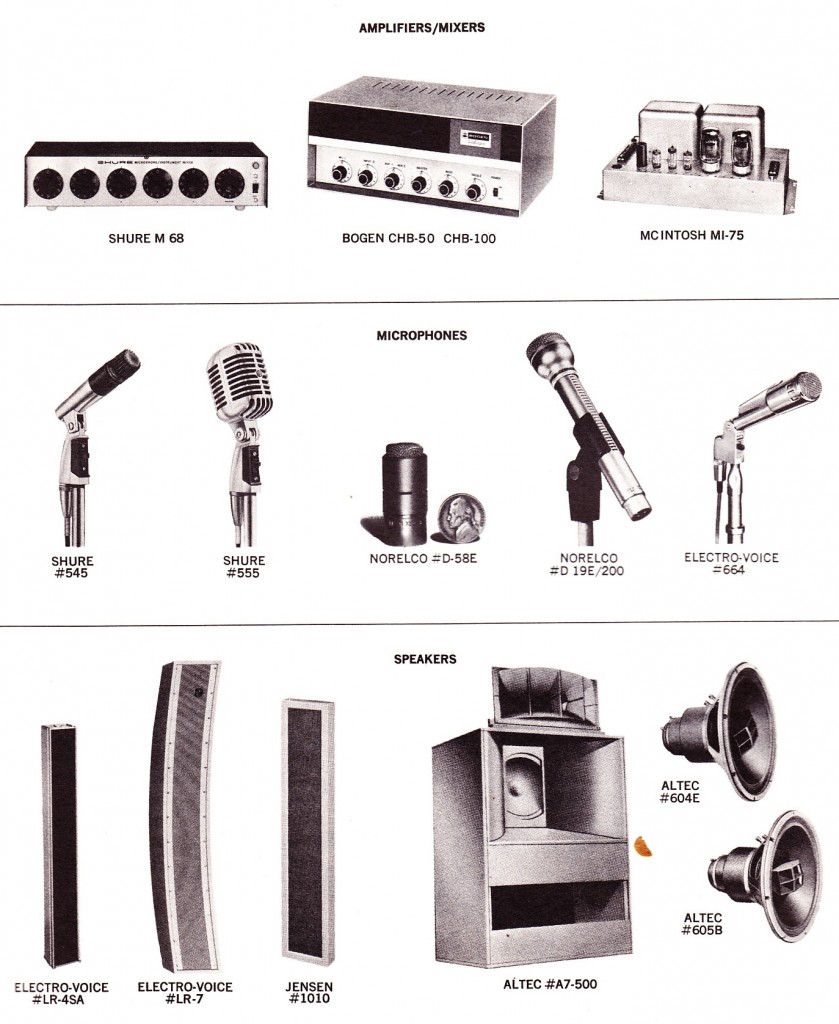

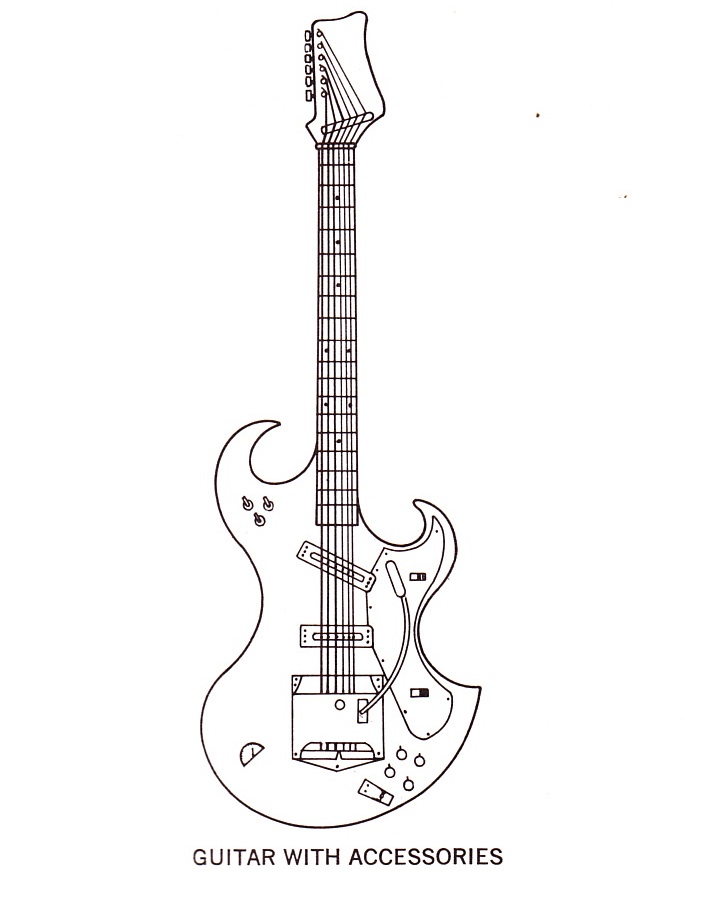

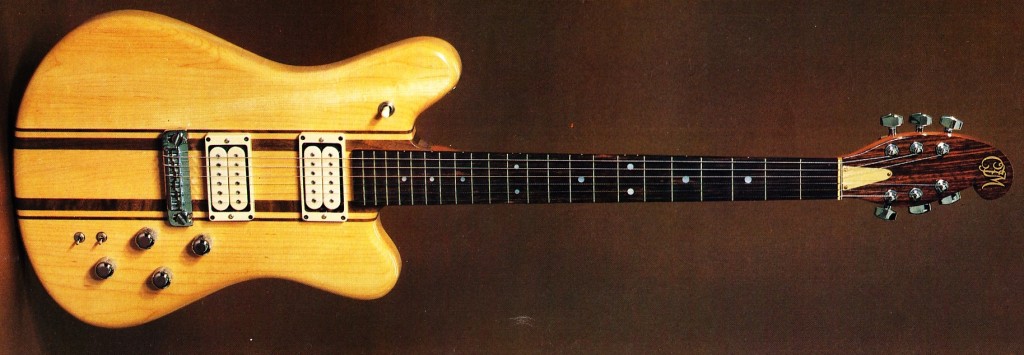

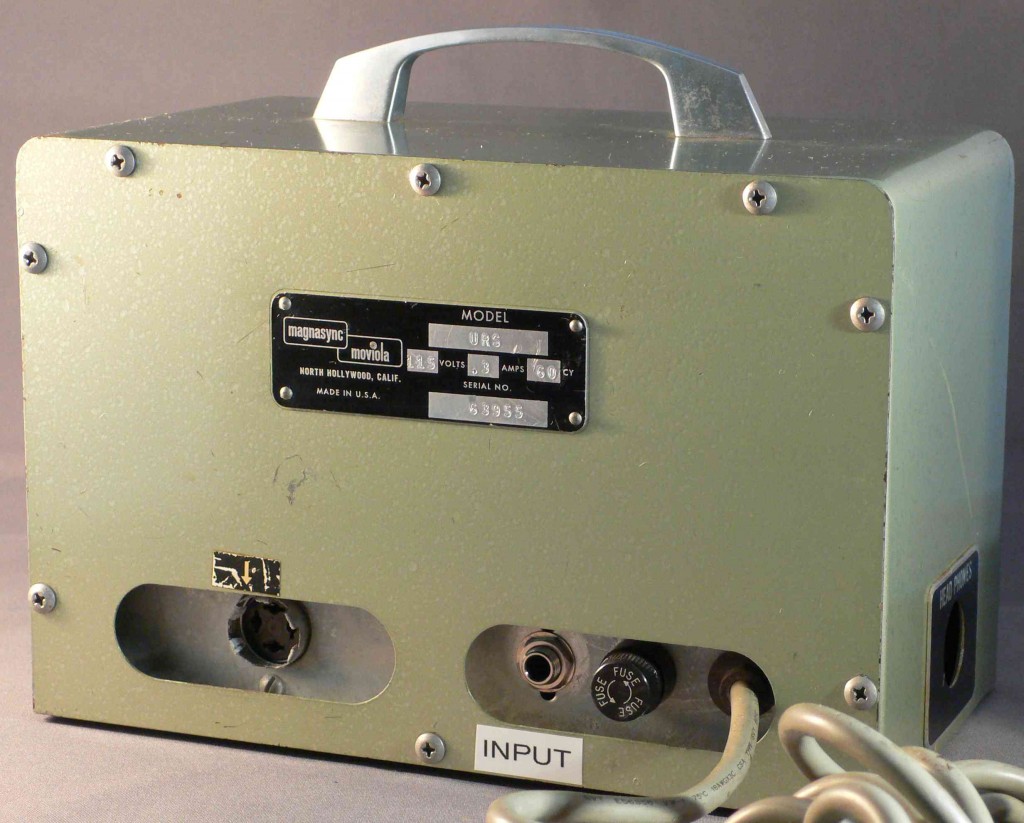

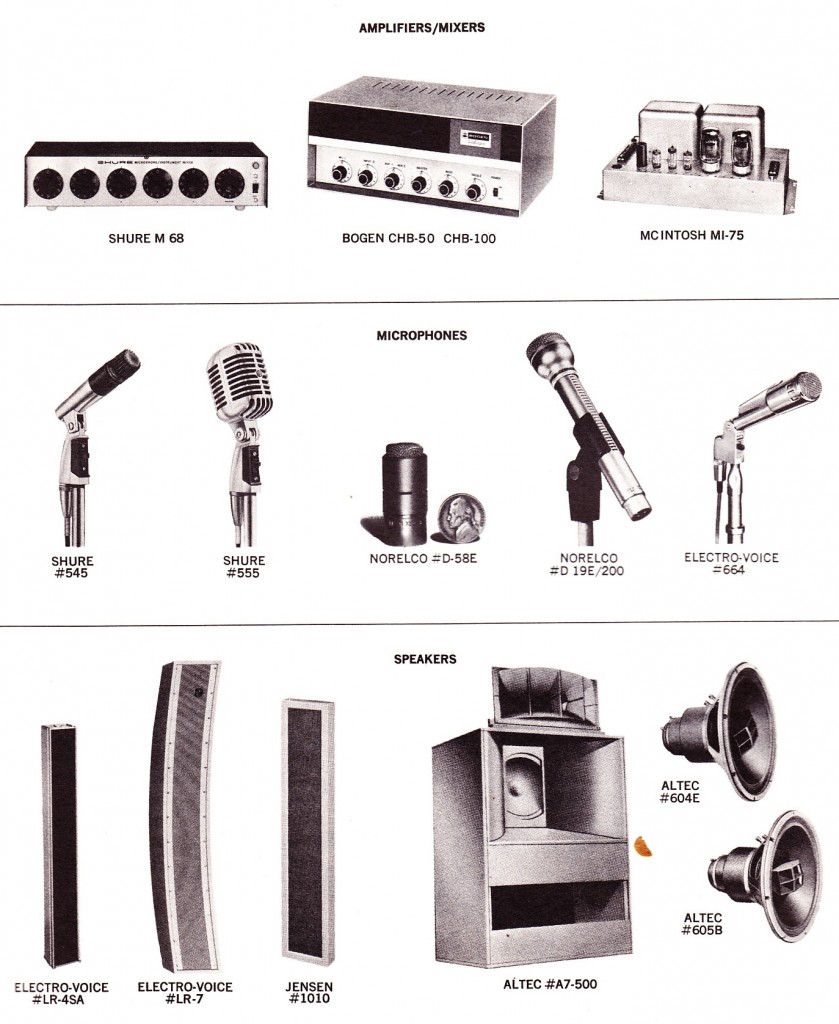

“PRR” parses the idea of what it takes to be a ‘professional rock and roll band’ in some interesting ways. There is the chapter on PA equipment, with the various above-illustrated items discussed (BTW, I still regularly find most of these items at the estates+fleas, so points to the author for accuracy), as well as a chapter each on Electric Guitars and Keyboards.

“PRR” parses the idea of what it takes to be a ‘professional rock and roll band’ in some interesting ways. There is the chapter on PA equipment, with the various above-illustrated items discussed (BTW, I still regularly find most of these items at the estates+fleas, so points to the author for accuracy), as well as a chapter each on Electric Guitars and Keyboards.

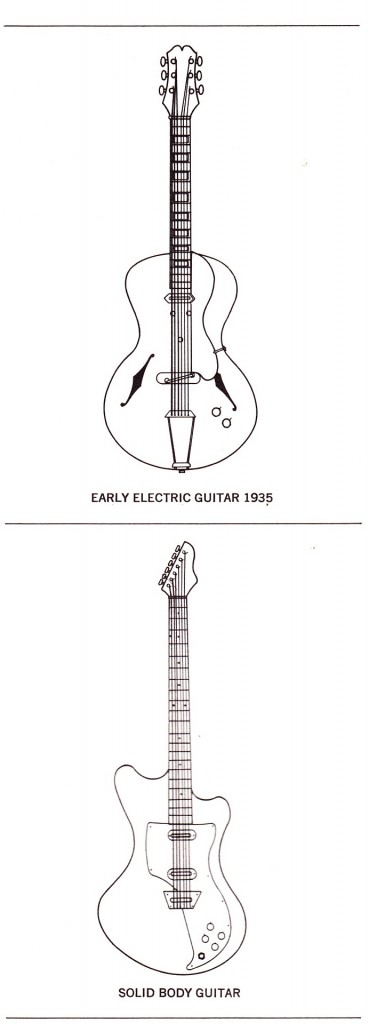

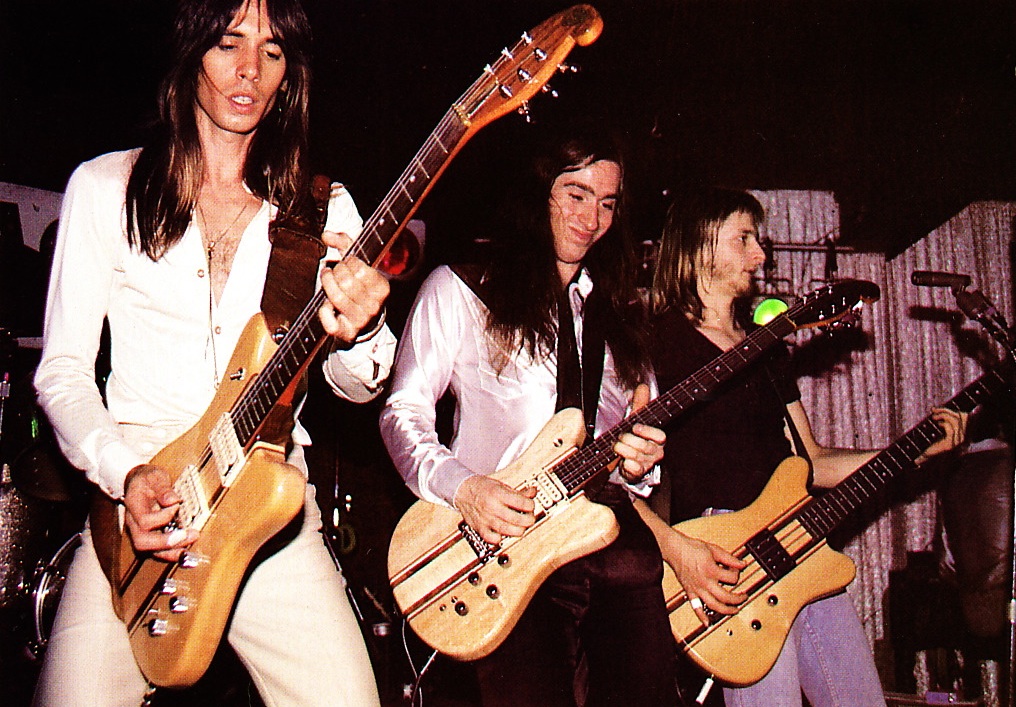

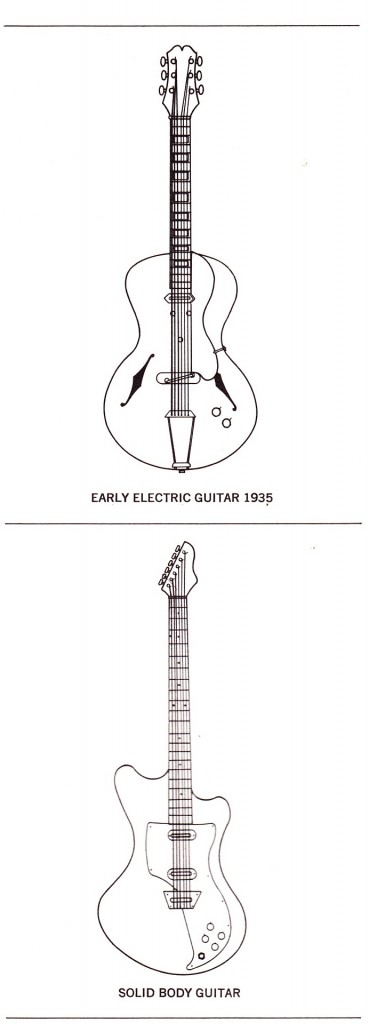

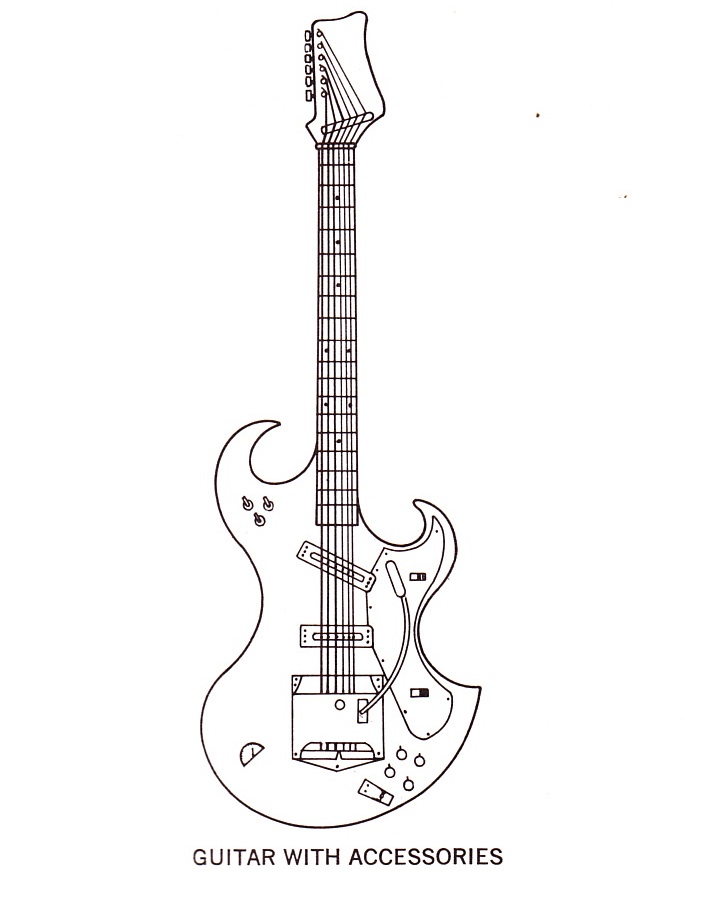

Above: the three types of Electric guitar: ‘Early,’ ‘Solid Body,’ and ‘With Accessories.’

Above: the three types of Electric guitar: ‘Early,’ ‘Solid Body,’ and ‘With Accessories.’

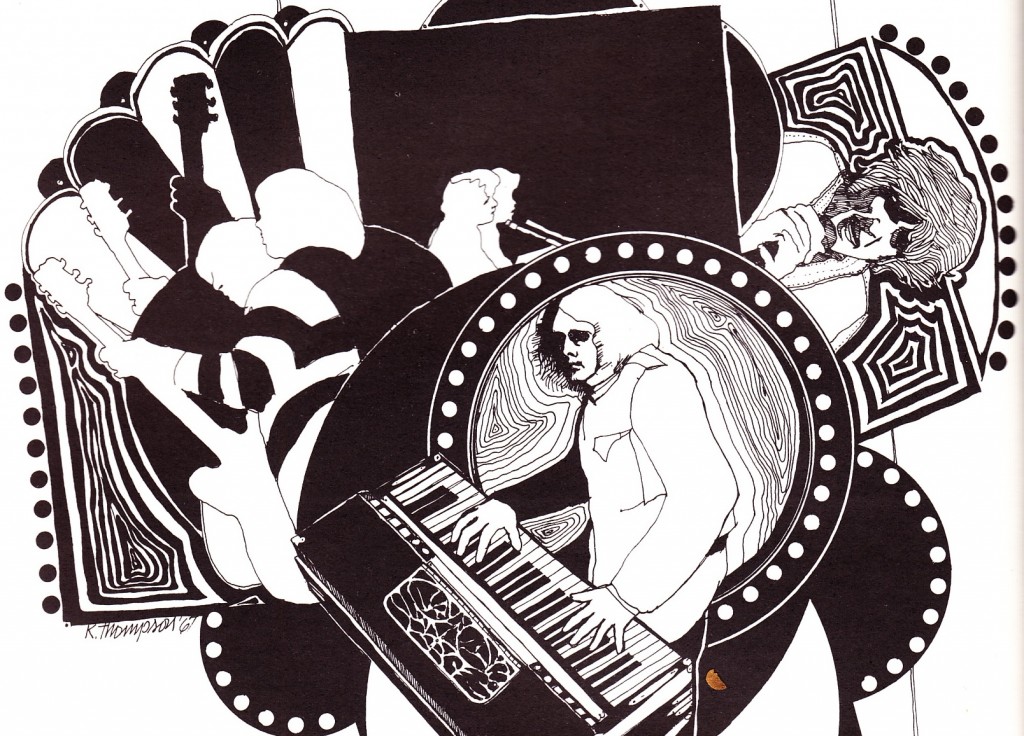

Above: The Rock Organ Player

Above: The Rock Organ Player

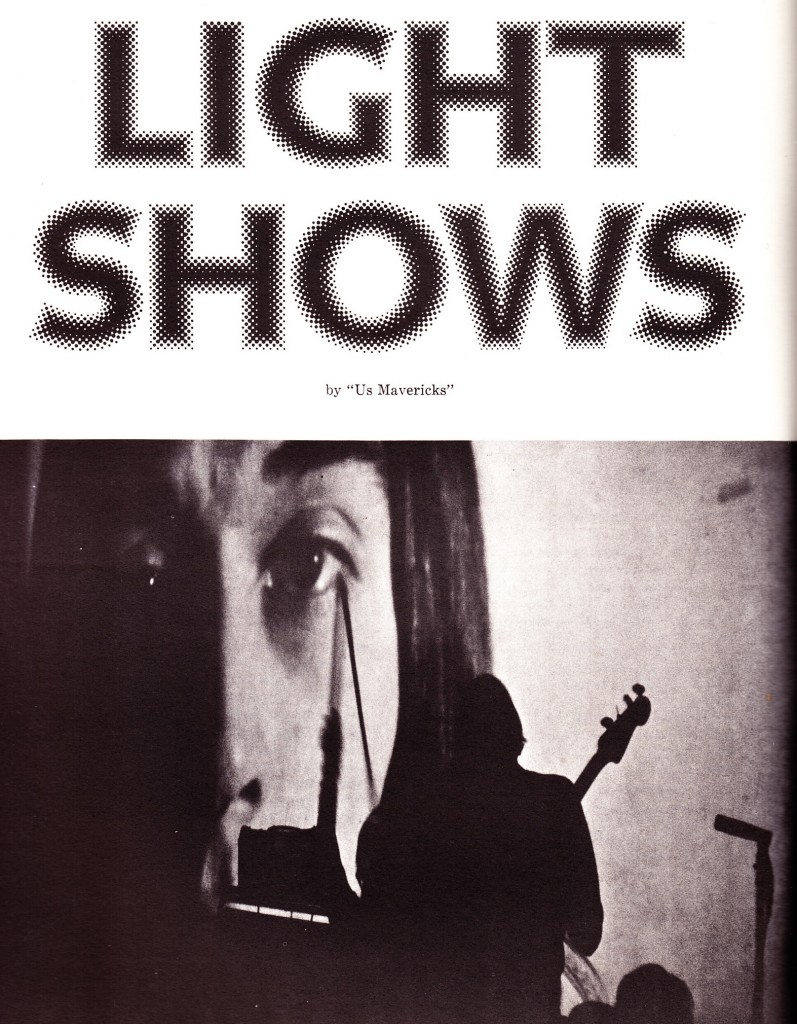

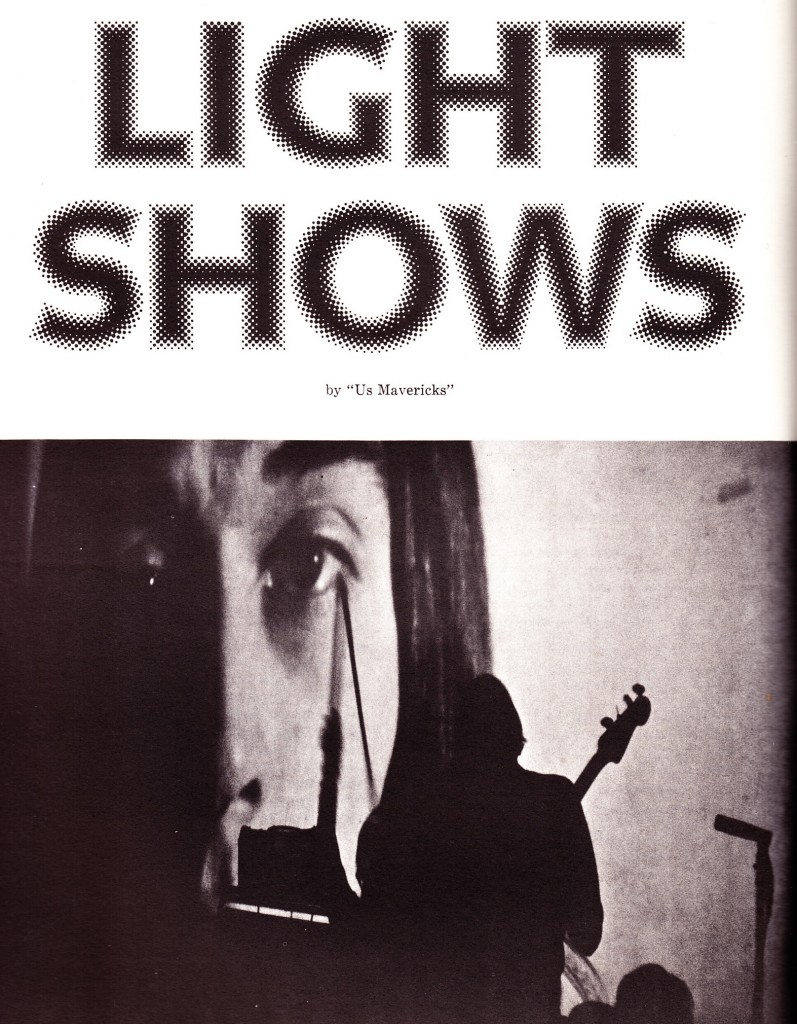

We also get chapters on putting a band together, chords, songwriting, lead-singing, hitting-the-road, and managers/agents/publishers. Somewhat more surprising is the in-depth chapter on how to locate and buy stage-clothing and the chapter on light-shows.

I think it’s somewhat interesting to learn how important the idea of visual-accompaniment-to-music was in those early years of the Rock industry. We’ve been told so often how MTV changed the visual/sonic balance of musical-signification so drastically, to such varied effect as manufacturers’ increasing the size of their logos on equipment (E.G., Zildjian Cymbals) and even the barring of rock-stardom to homely female performers (I.E., the Janis-Joplin-wouldn’t-have-made-it-today assertion). I can’t really say that this changes the argument, but it’s worth consideration.

I think it’s somewhat interesting to learn how important the idea of visual-accompaniment-to-music was in those early years of the Rock industry. We’ve been told so often how MTV changed the visual/sonic balance of musical-signification so drastically, to such varied effect as manufacturers’ increasing the size of their logos on equipment (E.G., Zildjian Cymbals) and even the barring of rock-stardom to homely female performers (I.E., the Janis-Joplin-wouldn’t-have-made-it-today assertion). I can’t really say that this changes the argument, but it’s worth consideration.

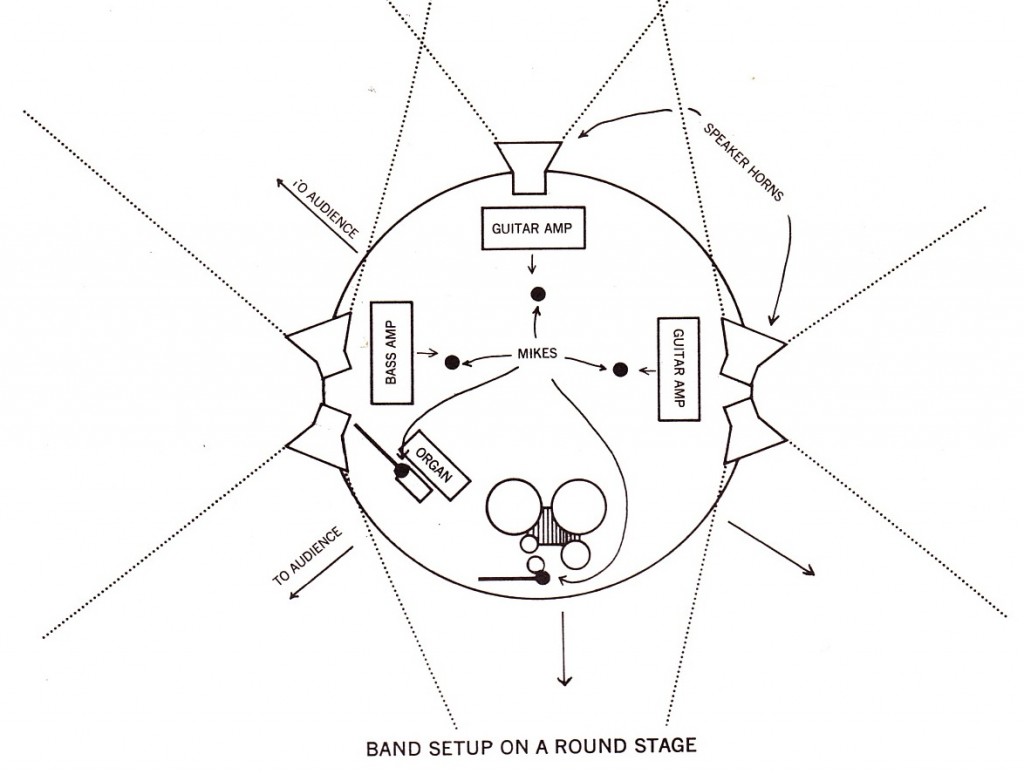

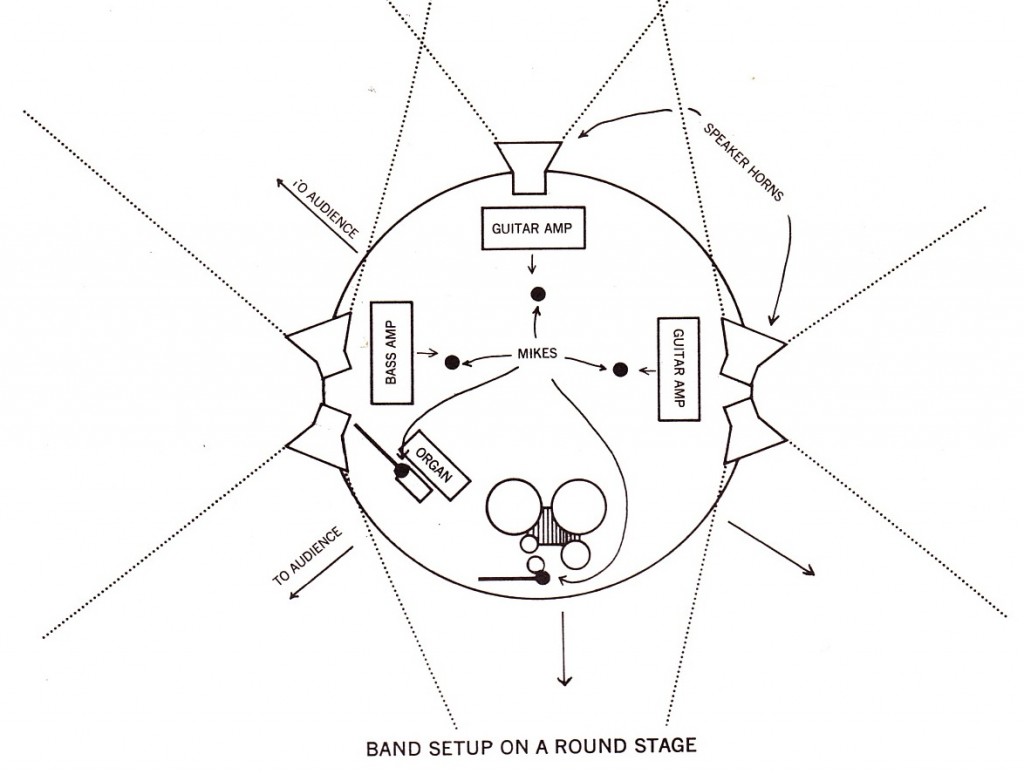

“PRR” also has a number of charming anachronisms, such as the diagram above. The authors felt it necessary to explain how a group should properly stage their gear on BOTH of the common types of stages: the theatre-type stage (band faces the audience) and, of course, the round stage. Wow. Were rock-shows on round-stages really that common in 1967? I’ve performed probably a thousand shows since the early 1990s, in venues as small as basements and as big as 10,000+ festivals, and never once on a round stage with the audience on all sides. Crazy.

“PRR” also has a number of charming anachronisms, such as the diagram above. The authors felt it necessary to explain how a group should properly stage their gear on BOTH of the common types of stages: the theatre-type stage (band faces the audience) and, of course, the round stage. Wow. Were rock-shows on round-stages really that common in 1967? I’ve performed probably a thousand shows since the early 1990s, in venues as small as basements and as big as 10,000+ festivals, and never once on a round stage with the audience on all sides. Crazy.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about “PRR” is the subject that it totally omits: there is nothing offered on the subject of recording. Not demo recording, not studio recording. No mention. Also lacking is a chapter on promotion and publicity. To most musical groups today, these seem to be the central issues that occupy most of their energy: thanks to all of the incredible, affordable audio-recording equipment and software we have now, recording and composing music have effectively become the same task; they are inseperble activities. Likewise, the public promotion, marketing, and branding of a musical project can now begin as soon as the first track is mixed down.

*Is there a similar book to “PRR” published for the modern musical era?

*If a high-school age band were today to study and implement the ideas in “PRR,” could they generate a 1968-type garage-rock group?

*Did anyone reading this purchase “PRR” as a young musician? Did you find it helpful?

Next up in this series: “Making Four Track Music,” John Peel, 1987.

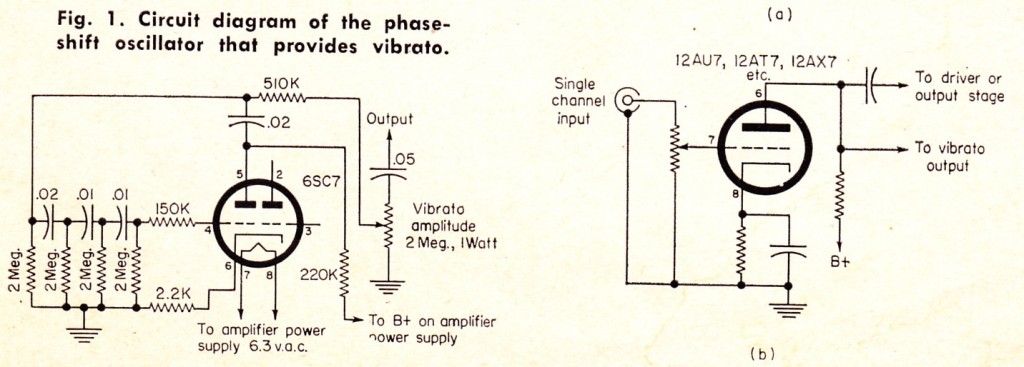

Download a short article from 1962 by one F.H. Calvert on the subject of adding a vibrato circuit to any vacuum-tube audio amplifier:

Download a short article from 1962 by one F.H. Calvert on the subject of adding a vibrato circuit to any vacuum-tube audio amplifier: